The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes being corrected. Even when the revolutionist might himself repent of his revolution, the traditionalist is already defending it as part of his tradition. Thus we have two great types — the advanced person who rushes us into ruin, and the retrospective person who admires the ruins. He admires them especially by moonlight, not to say moonshine. Each new blunder of the progressive or prig becomes instantly a legend of immemorial antiquity for the snob. This is called the balance, or mutual check, in our Constitution.

—G.K. Chesterton

A couple of years ago, I published a long piece for De Civitate in support of civil marriage. The “purpose of civil marriage,” I wrote, “is to promote positive procreation, which includes bearing and raising children, insofar as possible, within their intact families, so that they become productive, responsible, adult members of society… [I]t is a wise and prudent public policy.” I also argued against redefining civil marriage to include other loving, consensual, adult sexual relationships, on the grounds that doing so would undermine its public policy objectives while (paradoxically) opening the institution to charges of indefensible discrimination. I concluded, “A vote to redefine civil marriage is, in the final analysis, a vote to end civil marriage.”

Having said all that, I added in a postscript: “It is not unreasonable to want to abolish civil marriage entirely, on the basis that government interference in marriage does far more harm for children and the culture than it does good. I don’t think that’s true, but I’ve heard some good arguments (or at least starts-of-arguments) that make me suspect I could be wrong.”

In the years since I wrote that, those “starts-of-arguments” have blossomed, and I’ve come around to their position: civil marriage should cease to exist.

Admittedly, this is a little like demanding the execution of a man who is already tied to the gallows. A number of states, including my own, have indeed redefined civil marriage to embrace all conensual, adult, sexually-active couples. There is a good chance that the Supreme Court will impose that redefinition on the rest of the country sometime in June of this year.†† The inexorable logic of that decision is already beginning to grind up the institution of civil marriage: although marriage’s discontents are (wisely) keeping their powder (mostly) dry until the Supreme Court can confirm the redefinition of civil marriage, the Sister Wives court case moves steadily through the Courts of Appeals – destined to win a right to multiple civil marriage – and less-radical defenders of same-sex marriage have been reduced to nonsensical and self-defeating arguments as they try to explain why polygamy is “different” (N.B.: the smart ones – the real anti-marriage radicals – are just shutting up). As I argued in 2012, once you have removed the essential procreative element from civil marriage, you have no rational basis under the Fourteenth Amendment to deny access to the institution to any adult persons, in any number or combination, whether sexually involved or not. To attempt to do so is, ironically, unconstitutional discrimination that violates the Equal Protection clause. One woman, three men? A man and his sister? A convent full of nuns? All fair game, as our courts are about to discover, hollowing out the idea of civil marriage to the point of nullifying its putative positive policy effects – indeed, altering it so radically that “civil marriage,” as hitherto understood, ceases to exist in any meaningful sense. Justice Kennedy is on the precipice of taking this particular Ship of Theseus, sinking it, quarrying fresh limestone from a deposit on the opposite side of the world, building that stone into a two-star motel called “Jerry’s,” scribbling “Ship of Theseus” in chalk on a wall behind the third-floor ice machine, and claiming that the hotel is the very same Ship of Theseus. Our chattering class will crown him a new Solomon for this. Brace yourself.

On the other hand, meh. The decay of civil marriage is nothing new. The collapse was commenced, enthusiastically, by heterosexuals, who demeaned the institution, redefined it to make it routinely dissoluble in “no-fault” divorce, and reimagined our cultural and legal landscape to protect both deliberate sterility within civil marriage and sexual activity, even childbearing, outside it (even in adultery!). It was hardly fair of us to sit around enjoying the early stages of the cancer that has invaded civil marrage, only to (quite suddenly) develop scruples when gays and lesbians and polyamorists said they wanted to join the sexually-liberated fun! And so they have. The procreative essence of civil marriage has been mortally wounded for a long time – since long before Hillary Goodridge came on the scene.

But why point fingers at all? It’s water under the bridge, now. Civil marriage is (depending on your jurisdiction) either not-quite-dead or quite-dead, but everyone already knew that, and it’s not why you’re reading this post. The interesting part of my title was “(And It Deserved To Die)”. So let’s talk about that.

Two episodes from my real life:

Two years ago – just about two months after my blog post defending the civil institution of marriage – I got married. It was glorious. There’s no other word for it. My bride, resplendent, surrounded by her best friends (who had helped me orchestrate her engagement) and her loving family, joined me at the altar as, before our entire community, asking the sacramental grace of God to sanction and strengthen our union, we freely professed unbreakable, lifelong vows to love and honor each other, and to accept children into our lives. We sang the Litany of the Saints and Panis Angelicus. We read Scripture – “Now, Lord, you know that I take this wife of mine not for lust, but for a noble purpose!” – and, above all, we received the Holy Eucharist, that great concrete act of Christ’s love for us, of which our own marital love is only a prefigurement. Then we threw a pretty incredible party and repaired to the St. Paul Hotel; at long last, we were prepared to physically enact the vows we had just professed before God and Man; at long last, we were united as a family, ready to do our part as the brick and mortar of human society. (Our daughter was born 18 months later.)

Also, there was cake. And I’m not a cake person, but even I couldn’t get enough of that cake. Wedding cake is great.

In short, this was the most exalted day of my life, a day on which my bride and I exercised our solemn, free, and absolute right to take an unimpeded spouse of our mutual choice, and solemnly assumed all the responsibilities that accompanied those ferdful vows.

“Exalted,” however, is not the first word that comes to mind when I remember the day, one week prior, when I procured my marriage license. This is an undignified experience by any measure: we were commanded to report to the City of Edina DMV (which handles marriage licenses), get in line for a number, explain why we’re there, get a number, sit in the shabby DMV chairs and fill out forms in triplicate (really) against the dim DMV lighting, wait for our number, and eventually spend ten minutes with a kindly bureaucrat who was very happy for us, but who also made us wait around to run Martha’s driver’s license a few times (apparently the database was having troubles). When all was said and done, we handed over a certificate stating we’d received State-approved pre-marital education, which reduced our fee from $115 to $40. Then we gave her the $40, and she handed over a license granting us official permission to get married. I had expected to be proud to do my “bit” for civil marriage, but, instead, I left angry – and I didn’t understand why.

It took me some time to come to grips with that feeling, but, eventually, I think I figured it out. It came from that old and very helpful conservative instinct which says: the State has no right to claim authority over civil institutions – even public ones – which precede it… not even when the State’s claim is rationally related to some good end. The problem with state licensure of hairdressers is not merely that it’s bad economics; even if it were good economics, it would be a tremendous infringement on the basic liberty of innocent people to start and operate innocent, harmless businesses. The reason we all objected to the Supreme Court’s radical expansion of eminent domain in the Kelo decision is not because governments are likely to make bad choices if given the power to take private property and give it to other private developers (though they are); it’s because there is a fundamental human right to private property that pre-exists the State, and which can only be overridden for grave, fundamentally public needs. The reason the State should not tax the Church is not merely because the Church does a lot of good for the State in the form of charitable works; it’s because the State simply has no legitimate claim on the Church, which precedes it.

So, too, with marriage: marriage existed long before the State and will continue to exist long after it, and all mankind has a right to marry, with or without a state license, with or without paying the state’s $110 marriage fee. The state may have some say in recognizing my marriage, after the fact, but to license it? I think not. Because civil marriage is actively imploding under the weight of the sexual revolution, it’s difficult to see what a fantastically huge intrusion the State is making here, but consider the situation as little as twenty years ago: if you got married privately (or in the Church) without the State’s blessing, there were 16 U.S. states (including Minnesota) where you could go to jail under fornication laws. As I will show later on, the system of marriage licensure is designed – and for most of its history has functioned – to force all citizens to submit the most important decision of their lives to the veto power of the State, whose judgment supersedes the judgment of the individuals getting married and the judgment of the Church. Giving Gov. Mark Dayton this power, even perfunctorily, did not sit well with me. The course of my life should be decided at the altar of God, not the Edina DMV.

There is much that is stupid in Griswold v. Connecticut – indeed, it is easily among the Top 20 Stupidest Decisions of the Supreme Court – but, like most profoundly influential things that are incredibly stupid, it is built on a kernel of truth:

We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights — older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.

With these words, the Court ruled that the state of Connecticut lacked the power to regulate a certain aspect of marriage. The particulars of their (otherwise silly) ruling are not relevant to this post, but, in declining to permit State intrusion on the marital union, the Court was echoing that great old Catholic conservative, Pope Leo XIII, who wrote in his encyclical Arcanum:

Marriage has God for its Author, and was from the very beginning a kind of foreshadowing of the Incarnation of His Son; and therefore there abides in it something holy and religious; not extraneous, but innate; not derived from men, but implanted by nature. …[O]ur predecessors, [therefore], affirmed not falsely nor rashly that a sacrament of marriage existed ever amongst the faithful and unbelievers. We call to witness the monuments of antiquity, as also the manners and customs of those people who, being the most civilized, had the greatest knowledge of law and equity. In the minds of all of them it was a fixed and foregone conclusion that, when marriage was thought of, it was thought of as conjoined with religion and holiness. Hence, among those, marriages were commonly celebrated with religious ceremonies, under the authority of pontiffs, and with the ministry of priests. So mighty, even in the souls ignorant of heavenly doctrine, was the force of nature, of the remembrance of their origin, and of the conscience of the human race. As, then, marriage is holy by its own power, in its own nature, and of itself, it ought not to be regulated and administered by the will of civil rulers, but by the divine authority of the Church, which alone in sacred matters professes the office of teaching.

[Moreover], through addition of the sacrament the marriages of Christians have become far the noblest of all matrimonial unions. But to decree and ordain concerning the sacrament is, by the will of Christ Himself, so much a part of the power and duty of the Church that it is plainly absurd to maintain that even the very smallest fraction of such power has been transferred to the civil ruler.

Pope Leo, it turns out, was not a fan of civil marriage. He considers marriage a fundamentally religious institution, even among the “heathen.” Pope Leo even takes the trouble to name and define “civil marriage” – using a definition rather similar to the one Robert George* has used in defending the institution – specifically so that the nine paragraphs of blistering invective the Pope then heaps on the idea might be more clearly understood (Arcanum 17-28).

In Pope Leo’s telling, State intrusion upon marriage is not to protect it, but to undermine it. Marriage can protect itself fairly well, because it is a natural institution, supported by even the pagan religions, and ultimately redeemed and elevated by Jesus Christ. The State has no legitimate role in defining marriage, despite its avowedly major impact on public welfare (Arcanum 26). Throughout antiquity, whenever the State tried to assert even limited control over marriage, it caused corruption and harm, says the Pope:

All nations seem, more or less, to have forgotten the true notion and origin of marriage; and thus everywhere laws were enacted with reference to marriage, prompted to all appearance by State reasons, but not such as nature required. Solemn rites, invented at will of the law-givers, brought about that women should, as might be, bear either the honorable name of wife or the disgraceful name of concubine; and things came to such a pitch that permission to marry, or the refusal of the permission, depended on the will of the heads of the State, whose laws were greatly against equity or even to the highest degree unjust. Moreover, plurality of wives and husbands, as well as divorce, caused the nuptial bond to be relaxed exceedingly. Hence, too, sprang up the greatest confusion as to the mutual rights and duties of husbands and wives, inasmuch as a man assumed right of dominion over his wife, ordering her to go about her business, often without any just cause; while he was himself at liberty “to run headlong with impunity into lust, unbridled and unrestrained, in houses of ill-fame and amongst his female slaves, as if the dignity of the persons sinned with, and not the will of the sinner, made the guilt.” When the licentiousness of a husband thus showed itself, nothing could be more piteous than the wife, sunk so low as to be all but reckoned as a means for the gratification of passion, or for the production of offspring. Without any feeling of shame, marriageable girls were bought and sold, tike so much merchandise, and power was sometimes given to the father and to the husband to inflict capital punishment on the wife. Of necessity, the offspring of such marriages as these were either reckoned among the stock in trade of the common-wealth or held to be the property of the father of the family; and the law permitted him to make and unmake the marriages of his children at his mere will, and even to exercise against them the monstrous power of life and death. (Arcanum 7)

I myself have argued that, while the Church maintains final authority over the sacrament of marriage, the State must have authority over the contract of marriage, so as to ensure that children are raised in a healthy environment. Pope Leo disagrees:

Let no one, then, be deceived by the distinction which some civil jurists have so strongly insisted upon – the distinction, namely, by virtue of which they sever the matrimonial contract from the sacrament, with intent to hand over the contract to the power and will of the rulers of the State, while reserving questions concerning the sacrament [to] the Church. A distinction, or rather severance, of this kind cannot be approved; for certain it is that in Christian marriage the contract is inseparable from the sacrament, and that, for this reason, the contract cannot be true and legitimate without being a sacrament as well. For Christ our Lord added to marriage the dignity of a sacrament; but marriage is the contract itself, whenever that contract is lawfully concluded. (Arcanum 23)

I first encountered Pope Leo’s encyclical in May of 2012, and I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it at the time. I tried to reconcile it with my own position in support of civil marriage, but it posed considerable difficulties. Some of what he said could be explained away as a defense of the prerogatives of the Church with respect to the baptized only… but much could only be seen as a direct attack on an institution I had dedicated quite a bit of time to defending. This caused me to doubt† my position, and contributed to my growing sympathy for those who would abolish civil marriage. But it wasn’t until I walked into the license bureau, begging, under penalty of law, for the State of Minnesota to please let me marry my girlfriend, with a stack of $10 bills to ensure the State smiled on my humble request, that Pope Leo’s words finally clicked with me.

So, within a few weeks of my wedding, I had developed reservations about the whole “civil marriage” enterprise. But I still had grave concerns about the alternative: in a world without civil marriage, how do we ensure that children are raised by both their parents? How could we contemplate removing one of the few legal incentives to responsible procreation in a society where procreation is plunging and irresponsibility skyrocketing? What about all those arguments I laid out last time? Besides, the astute reader will note that my feelings, however strong, were mostly just feelings: to this point, the only actual arguments I’ve made are by analogy and authority, which is the weakest kind of proof, as the Angelic Doctor says.

A few months after my sacramental wedding, I attended my very first civil wedding. A distant cousin was tying the knot with her live-in boyfriend of several years. Here, again, I would have a chance to see the State’s noble administration of marriage in action. Here, I would be reassured of my own argument that civil marriage is the keystone of secular society – despite Pope Leo’s condemnation!

It was not to be. Quite the contrary: the civil marriage ceremony was, without exception or even serious competition, the most depressing ritual I have ever witnessed. (And I’ve been to an atheist’s funeral!) No part of it was particularly surprising – anyone with a Pinterest account or a TLC subscription will recognize the basic tropes of the outdoor civil wedding. We had the mason jars. We had the outdoor gazebo in the public park. We had the generic State-appointed “minister” (what exactly is he ministering?), smiling big and saying nothing for a minute or two in a parody of a homily. We had the cut-rate poetry readings (it’s been a while, but I’m fairly sure we even had “The Prophet” by Khalil Gibran), speaking of “love” in terms without content, challenge, or any thought of the fruits of specifically sexual love. Indeed, there was no hint of sexuality in the entire proceedings, other than the kiss at the end. You don’t think of Catholic wedding Masses as “intensely sexual” until you attend a typical civil wedding. It was as though marriage were just a party you threw to celebrate the fact that you found a good friend – a friend you’ve already been living with for a long while, and whom you may or may not choose to leave in the future. (Permanence was also not a prominent subject.)

The readings were followed by “vows” written by the betrothed, which really ought to have been called “tributes” (maybe “eulogies” if you wanna get Greek), because I don’t recall any actual vowing in them. There was, however, an awful lot of Gibran-style poetic rambling (only less skillful) and a few awkward attempts at humor. No doubt desperate to inject some kind of meaning into what was supposed to be a “special day”, the bride and groom found a couple of unique things to do. They did a “blending of the sands” ceremony, which was my favorite part of the wedding, both because I’d never heard of it before and because it was the only part of the ceremony that seemed to wink at the idea of “the two shall become one flesh.” Unfortunately, they prefaced it by playing the voiceover from Days of Our Lives, which was… well, it was unique, I guess. The other “unique” thing they did was, at the end of the ceremony, (which lasted a total of 11 minutes), rather than processing out, the entire wedding party rose and did the Harlem Shake.

This, friends, is what we advocates for civil marriage have devoted decades of effort, millions of words, and tens of millions of dollars, to defending, preserving, even extending.

I bear no ill will toward the couple: this is the culture they were raised in. This is what they understand marriage to be. They did the very best they could with what they had, and my only feeling is sadness that they have been deprived of a deeper understanding of marriage. When you are vowing neither faithfulness nor fruitfulness nor anything in particular except to maybe put up with your spouse’s preference for putting the toilet seat up or down, what else is left to you but the Harlem Shake? They were a very nice couple, gracious hosts, and the wedding cupcakes were excellent. (Really. Top-flight.)

But we, the people on the Robert P. George side of the fence, ought to be asking ourselves: what went wrong? Civil marriage (as popularly practiced in the modern United States) bears about as much resemblance to a natural marriage (as popularly practiced among, say, common people at the height of Ancient Jewish civilization) as a Black Mass bears to a Catholic Mass. Of course, natural marriage itself is but a shadow of sacramental marriage (Arcanum 9, 39), but this government-thing-we-call-marriage isn’t even that. The most favorable construction you can give to civil marriage is that it’s a parody of marriage proper. How did we miss this? I shared my experience with a friend, who was skeptical of my shifting opinion on marriage… until the day he went to a civil wedding, which is when he texted me, “Yeah, it may be time to repeal all this.” I have wondered ever since: how many of civil marriage’s most prominent and valued defenders (who happen to be almost unanimously Catholic) have actually been to a civil ceremony before?

In the balance of this article, I would like to suggest that what went wrong with civil marriage is that we invented it.

Yes, invented it.

The history of marriage is a very complicated thing, full of changes and contradictions. Just about the only thing that every culture has in common is their absolute certainty that the way they understand and practice marriage is the only way it has ever been understood, ever will be understood, or ever could be – a certainty that is absolutely incompatible with every other culture’s equal but opposite certainty about their understanding of marriage. The more you read about it, the less you’re able to hold onto simple narratives about the civilizational meaning of marriage, which makes plenty of modern conservatives and progressives alike (the kings of “simple narratives”) look very ridiculous.

Even Pope Leo gets it wrong when he argues (Arcanum 19) that marriage has always been “conjoined with religion and holiness” among the “most civilized” examples of antiquity. Consider marriage at the height of the Roman Republic: the vast majority of marriages were conducted sine manu – wholly private agreements between spouses. To the extent that public marriage existed, the vast majority were coemptio marriages, which involved not a priest but an accountant (a public “scales-holder” who certified the notional “sale” of the bride to the groom). Rarest of all was conferratio, the public religious marriage ceremony that created indissoluble marriage… rare largely because the god Jupiter did not consider someone worthy of confarreatio unless they were an aristocrat, and also born to parents who were likewise married under confarreatio. Quite a lot of ancient marriage (sine manu included) involved the bare minimum required by natural law: mutual consent, expressed in some form, to enact a lasting sexual relationship, involving at least one man and one woman, directed toward the bearing and rearing of children. And, where it was more complicated, it was rarely to marriage’s benefit: Leo has already recounted for us the many perversions of marriage that have arisen throughout history – often with State support, sometimes not – leading to all sorts of bizarre, exploitative, and unnatural notions about marriage that infected whole epochs of human culture. Practically any ridiculous thing you can imagine about marriage has been fiercely believed by at least one civilization at some point in human history.

That includes us. Our civilization’s contribution to the history of marital error is the idea of government control over marriage. In the ancient world, the State recognized marriages, like any other contract. Occasionally, the State would even interfere (usually unjustly) with particular marriage contracts that it didn’t like, like those between slaves and freemen. But the State did not think that it owned or defined marriage, and did not presume to administer it. Depending on your time and place, marriage might be under the authority of your Church, or it might be under your own private authority, but it was never a tool of the State.

In the Christian Era, marriage throughout the West was explicitly handed over to the ecclesial power for administration and regulation. For over a thousand years, marriage was handled by churches, and the secular power’s job was to enforce the acts and proceedings of recognized churches. Jewish? The existence and validity of your marriage (or its dissolution) were for your religious courts to work out according to the terms of your religious kettubah. Muslim but stuck living in Christian Sicily? See your qādī. The Christian story of marriage jurisdiction is a little more complicated, because the Church and the secular power were so deeply entwined with each other throughout most of the period, but the ultimate authority of the Church over marital regulation, administration, and dissolution was not seriously questioned, even after the Reformation. The great Blackstone was still reporting on the authority of canon law over marriage in the 1760s, two hundred years after the King and Parliament became heads of the English Church.

Blackstone also reported – one can’t help noticing – that Christian marriage was indissoluble, except by an explicit act of Parliament (the top religious authority of the Anglican Church).+ Jews could divorce, following the kettubah and Mosaic Law, as mediated by rabbinical courts, but Quakers, following a strict interpretation of Matthew 19:9, considered marriage even more indissoluble than the Anglicans. The State had no say in this, because marriage was not an institution of the State. Marriage was, first and finally, an institution of private, religious, and common life, contracted between the bride and groom and sealed by the blessing of whatever God they worshiped (as long as worship of their God was legal to begin with, that is). It’s worth asking ourselves, for a moment, how people of this time understood their marriages under this radically different – and ancient – legal regime.

For an Anglican Englishman of 1765, the experience of a wedding likely resembled my own: an exalted, chiefly religious, adventure. The vows of marriage – which brides and grooms did not write for themselves – were spoken before the whole community, and they bound each partner to a special form of love, a self-commitment that would be free, faithful, fruitful (and by “fruitful” I mean “sexy” and by “sexy” I mean “baby-making”), and forever.** (One might almost call it a “self-gift,” but that terminology wouldn’t be developed until the 20th century.) These terms were understood by even the simplest of citizens, they were expressed in and intimately tied to sexual intercourse (which was forbidden prior to marriage), and the details of their marriage contract were between themselves and (thanks to the Marriage Act 1753) their Church – but never the State. The marriage could be for politics or property or love, but, whatever the motivation for marriage, what marriage is was clear. For the English of 1765, even among those who married for love (which was most of them; the love match was already dominant in England by this time), the definition of marriage looked an awful lot like Robert P. George’s “conjugal view”.

The State had one job in all this, and one job only, which it performed with its usual muddling competence: the State enforced the terms of the contract. When one or both spouses violated the contract, it stepped in to adjudicate, like any other contract. That’s all. The State did not define the contract, its powers to regulate or authorize the contract were severely limited and incidental to its entanglement with the established Church, and it sure as hell didn’t administer the contract. Even the Marriage Act 1753, which merely stated that the State would not recognize a marriage contract without banns, was a very bold step for the time, and Parliament had neither the authority nor the appetite for more. The contract was defined and administered by the various churches, which each (in turn) acted according to their best understanding of natural law (which was, for the Anglicans, at least, really quite good).

Then, one fine summer’s day, the French Revolution broke out of the Bastille like herpes. Now, the French Revolution was fantastically evil for a wide variety of reasons, but I just want to deal with its invention of civil marriage.

You see, the sans-culottes and their thought-leaders really disliked the Catholic Church. Some of their reasons were good, though a lot of it was just bigotry and hatred fueled by left-wing atheistic ideology (recall that the French Revolution saw both the genesis and the high-water mark of much of the modern Left). The Church was very well-established in France and, whatever the reasons, the revolutionaries really wanted to take away its power and privileges. In 1790, having seized control of the country,they passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which effectively abolished Catholicism, by subjecting priests, bishops, and doctrine to the control of the State. Those who refused became criminals, and many were put to death – or simply murdered by the progressive mob.

Finally, on 20 September 1792,‡ the Legislative Assembly stripped the Church of all its authority regarding marriage. For the contract to be recognized by the State, it would henceforth have to be executed before secular representatives of the State, according to State policies and procedures, in a State-sanctioned “ceremony,” and under the absolute authority of the State both before and for the duration of the marriage. Throughout history, the State had, on and off, interfered with marriage, but now the French Revolutionaries launched a wholesale government takeover of the entire institution. “Civil marriage” was born.

This was not simply a matter of civil housekeeping, nor of mere disestablishment. As Suzanne Desan shows in her highly-regarded work, The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France, the revolutionaries’ takeover of marriage was explicitly ideological:

[B]etween February and September 1792, as republican sentiment, patriotic fervor, and anticlericalism all grew stronger, certain legislators gradually envisioned an increasingly central role for marriage in the constitution of citizenship. In their recurrent debates over the état civil… redefin[ing] marriage solely as a civil contract under the aegis of the state stirred up endless controversy… In the eyes of proponents, [“]regenerated[”] marriage would become the natural, social, legal, and moral bond that tied the individual citizen to society and to the patrie… The state was now to become the sole guarantor of the legal status of the citizen. […]

“Marriage belongs to the political order,” asserted Muraire. Tellingly, he spoke of the nuptial act as that “interesting moment when, recognizing that his duties toward society are not limited to personal devotion, [the citizen] engages in a contract to reproduce himself.” […]

By the summer of 1792, Gohier proposed that marriage and all other civil acts, such as birth, death, and inscription into the national guard, be celebrated on a newly constructed Altar of the Patrie… Since spouses should remember that they belonged to the patrie even before they belonged to each other, the civil marriage vow would be sealed with the exultant cry of “Live free or die!” […]

In this same vein, knitting marriage ever closer to patriotism, the deputy Jean-Baptiste Jollivet proposed that loyalty to the nation be part of the legal definition of marriage: it would be a freely chosen contract in which couples pledged “to live together and to raise their children with love of the patrie and respect for its laws” Within its very definition, marriage now implied a political as well as a personal commitment. (Desan 54-58)

The French Revolution took marriage into the State in order to sever the citizen’s ties to the Church and to civil society, binding him closer to the State by converting the most important private relationship in his life into a political communion with the State. This is civil marriage: not a rational exercise of State power to encourage mothers and fathers to participate in raising their own children, but a nightmare straight out of the Life of Julia. On 20 September 1792, the Revolutionary French Republic took marriage out of the Churches, lifted it away from common civil life, and set it on a new path leading directly to the Edina DMV.

Not coincidentally, 20 September 1792 was also the day France legalized no-fault divorce. From the moment the State commenced its usurpation of marriage, it was less than six hours until they fundamentally redefined it from an indissoluble contract to one that could be dissolved at will – the first of many redefinitions marriage would undergo once it became the State’s plaything. Pope Leo was not surprised. After all, how could anyone expect people to stay married their whole lives when marriage no longer confers the transformative grace of God, but merely the polite smile of the State? The French catastrophe loomed large in the background of this section of Arcanum:

When the Christian religion is reflected and repudiated, marriage sinks of necessity into the slavery of man’s vicious nature and vile passions, and finds but little protection in the help of natural goodness. A very torrent of evil has flowed from this source, not only into private families, but also into States. For, the salutary fear of God being removed, and there being no longer that refreshment in toil which is nowhere more abounding than in the Christian religion, it very often happens, as indeed is natural, that the mutual services and duties of marriage seem almost unbearable; and thus very many yearn for the loosening of the tie which they believe to be woven by human law and of their own will, whenever incompatibility of temper, or quarrels, or the violation of the marriage vow, or mutual consent, or other reasons induce them to think that it would be well to be set free. Then, if they are hindered by law from carrying out this shameless desire, they contend that the laws are iniquitous, inhuman, and at variance with the rights of free citizens; adding that every effort should be made to repeal such enactments, and to introduce a more humane code sanctioning divorce.

Now, however much the legislators of these our days may wish to guard themselves against the impiety of men such as we have been speaking of, they are unable to do so, seeing that they profess to hold and defend the very same principles of jurisprudence; and hence they have to go with times, and render divorce easily obtainable. …

Truly, it is hardly possible to describe how great are the evils that flow from divorce. Matrimonial contracts are by it made variable; mutual kindness is weakened; deplorable inducements to unfaithfulness are supplied; harm is done to the education and training of children; occasion is afforded for the breaking up of homes; the seeds of dissension are sown among families; the dignity of womanhood is lessened and brought low, and women run the risk of being deserted after having ministered to the pleasures of men. Since, then, nothing has such power to lay waste families and destroy the mainstay of kingdoms as the corruption of morals, it is easily seen that divorces are in the highest degree hostile to the prosperity of families and States, springing as they do from the depraved morals of the people, and, as experience shows us, opening out a way to every kind of evil-doing in public and in private life. (27-29)

Pope Leo, being Pope Leo, goes on for another five or six paragraphs berating divorce, everyone who advocates for divorce, and everyone who advocates for civil marriage, which leads to divorce. I’ll spare you the block quotes – he’s made his point.

But nobody listened.

After Napoleon spread the new French civil code to the rest of Europe, marriage never recovered. England, though never conquered by Napoleon, adopted a similar attitude toward marriage a few decades later, as the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857 seized power over marriage for the State and (shock!) simultaneously legalized divorce (under certain, blatantly misogynistic, circumstances). Where colonialism did not impose State marriage, communism did, and, even as Pope Leo counseled steadfastness, the whole world eventually fell under civil marriage’s sway. The United States, already noted in Blackstone as something of a divorce hotbed, started getting into the marriage business in a big way after the Civil War, in order to regulate pensions (and Mormons).

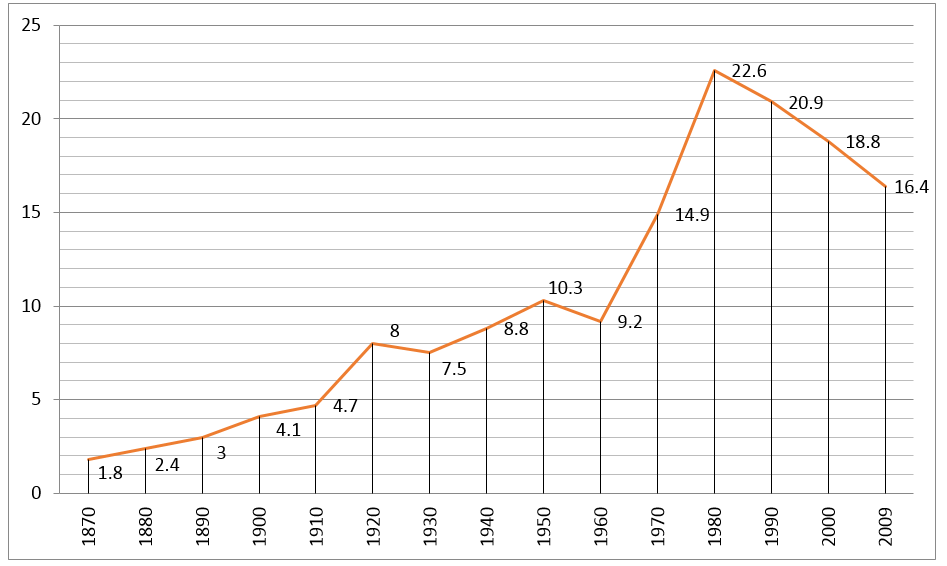

That, not entirely coincidentally, is when the federal government began tracking divorce statistics. The following table represents the number of divorces per 1,000 married women, by year. There is no word for this data other than “grim”:

SOURCES: source 1 – table 3, source 2 – table 117, source 3; figures for 1870 and 1880 are imputed from tables 1 and 3 here

There is a conservative trope – so much a trope now that even conservatives shy away from it – that marriage collapsed in the 1960s, and was peachy-keen when Leave it to Beaver was on the air, before Griswold v. Connecticut and the advent of no-fault divorce. This is not true. The divorce rate today is about twice what it was fifty years ago (in 1960), yes. But the divorce rate fifty years ago (in 1960) was about twice what it was fifty years before that (1910) – and that’s still more than twice as high as the divorce rate forty years earlier (1870), when it was already so high that Pope Leo was panicking about the dissolution of the family! The Sexual Revolution was fuel on the fire, yes, but marriages have been steadily burning up in this country, faster and faster, ever since the Civil War – that is, since the government takeover of marriage.

Pope Leo, writing in 1880, could imagine only one practical social evil arising from civil marriage: divorce. He predicted that it would grow and grow in just this way (“The Romans of old are said to have shrunk with horror from the first example of divorce, but ere long all sense of decency was blunted in their soul; the meager restraint of passion died out, and the marriage vow was so often broken that what some writers have affirmed would seem to be true — namely, women used to reckon years not by the change of consuls, but of their husbands.”), but it was the only evil he could see on the horizon.

Our imaginations are not so limited. We have corrupted marriage beyond the wildest nightmares of Pope Leo. We have converted for-cause divorce into no-fault divorce. We have, for the first time in the Christian Era, given social and legal sanction to contraception (which led to another host of social evils, which were in turn predicted by Pope Paul VI). We have developed artificial insemination – the creation of children with no reference to the nuptial act at all. We have started pretending, on legal birth certificates, that parents aren’t even parents (and non-parents are). We have consigned two generations to a culture of hooking-up and internet pornography. Our illegitimacy rate – which strongly correlates to future outcomes for children – is simply jaw-dropping, even to a jaded Millennial like me. Cohabitation is now the norm – and not cohabitation before marriage. Just plain cohabitation, with a beginning and an end and never a vow spoken. There’s time for that now, because young people are delaying marriage to the edge of historic norms. And when you factor out the educated class that knows how to get married and stay married, everything looks two or three times worse. Barely half of the least-educated class is raised by both mother and father, while the number of intact two-parent households only continues to fall.§

And should this litany really surprise us?

Civil marriage made people start thinking of marriage as something the government does. This is evident in all the recent same-sex marriage litigation, where it is now taken for granted that being unable to get a civil marriage is equivalent to an “inability to marry” and that that very deprivation inflicts “severe humiliation, emotional distress, pain, suffering, psychological harm, and stigma” on those so deprived.

But the idea of marriage-as-government-function has penetrated a lot deeper than litigation. The idea that marriage is just a “piece of paper” is everywhere, and, from what I’ve seen of civil weddings, they’re not wrong: practically and spiritually speaking, civil marriage is a coupon you wave so you can fill out a joint tax return and feel good about the State’s approval of your relationship. Conservatives fighting back against the “piece of paper” meme, unfortunately, often confirm the very thing they are refuting; instead of arguing that marriage precedes the State, many of them merely argue that it the State’s approval of your relationship really matters and that you need to get that joint tax return. Even our leading lights – heck, even I – while avoiding the obvious forms of this trap, have offered a vision of marriage that is something like: “Get married, because it will provide optimal social outcomes for you, the State, and the children you aren’t planning to have!” Progressives took the exalted, transcendant vow of marriage and flattened it into a government program. Conservatives have responded by arguing that it’s a really good government program, which most everyone should sign up for.

Even if this is true ¶: still! How drab, how empty! This is a vision of marriage worthy of the Edina DMV, and every bit as inspiring. When marriage was about something real, something dramatic, something human – the fires of Hell, the honor of the family, a solemn duty to a vulnerable party, or any of the hundreds of other things it has meant throughout human history – people wanted to be a part of it. People would die for it. But the vampiric State has drained those meanings from its parody of marriage, and that leaves very little. Deep down, nobody gives one slice of government cheese whether the State approves of their sex life. No one is going to martyr themselves for the “married filing jointly” checkbox on the 1040EZ. A dozen reality TV shows portray a wedding as a big, expensive party, a “day about me,” and that’s about it. (As usual, reality TV tells us more about ourselves than we care to admit.) If that’s all marriage is, why are we surprised that people don’t care as much about “making it legal”? Mere patriotism and tradition and rational self-interest were not enough to keep Pope Leo’s “Romans of old” from abandoning the nuptial institution in droves; why should we expect our citizens to do better? How are we surprised that the poor don’t wed when their whole understanding of wedding centers around a party they could never afford to throw?

This is, admittedly, one of those narrative-cultural arguments that drive progs crazy, because they involve thinking about human beings as something more than animals whose every action can be predicted by Social Science, Big Data, and Maslow’s Hierarchy… but these arguments have an unsettling track record of being right (the link covers two important examples; for more, see Arcanum and Humanae Vitae).

But this is not the only way civil marriage has promoted social injustice and contributed to its own disintegration. Civil marriage does not merely obscure the natural meaning of marriage for those who do not know it: it makes it impossible for those who do know the natural meaning of marriage to live it.

Consider two Catholics who marry, observing the prescribed canonical form like good papists. At the altar, they profess a lifelong vow to love one another as husband and wife, both when it is a joy and when it is a cross. If this were regular law, their mutual promise would constitute a verbal contract, and it could only be undone by annulling the promise on some grounds like duress.

But civil marriage is not regular law. There are typically not just one or two, but literally hundreds of witnesses to this contract. The participants must get pre-approval from the State to make the contract – at modest expense (though it is worth pointing out that the license fee is a highly regressive tax) – and are often given incentives to undergo specific training for understanding and embracing this contract. In many jurisdictions, the participants must undergo a blood test and physical medical examination prior to making the contract, to ensure the mutual fitness of the parties. A waiting period is almost universally required, again to ensure that the contract is entered into freely and fitly. A paper record of the contract is made immediately after, and it is immediately filed with the civil registrar. The actual vows – the contract itself – are now usually filmed, and the terms, for their part, are about as broad as they are plain: mutual, exclusive love and support that is free, faithful, fruitful, and forever – a big ask, but hardly “unconscionable” by the standards of the Second Restatement, especially given that this particular contract has been in regular use since before humans were literate. If this were regular law, a Catholic marriage would be about the rock-solidest contract in the world.

But civil marriage is not regular law. On the one hand, the State does far more than it usually does to ensure that those entering into it are free, capable, and fully understand what they are doing, putting up all sorts of barriers (putatively) to screen out those who don’t, and even prosecuting those who enter it fraudulently.

Then, having built a moat, earthworks, and an electric fence around the contractural sanctity of marriage… the State absolutely refuses to enforce the contract, or any of the terms. As David French put it, the State considers this expensive, laborious, ironclad contract “less binding than a refrigerator warranty.” The State ignores even the most egregious breaches of the contract – only a handful of states punish adultery, those laws haven’t even been enforced in decades, and they are likely unconstitional under the Supreme Court’s Lawrence v. Texas ruling.

And the State openly flouts the terms. If a married Catholic man decides he wants to abandon his wife and infant son so he can run off with his college-aged ex-student, he can go to the Church and ask for the dissolution of his marriage. The Church will point out that he vowed to stay and care for his family for the rest of his natural life, and, if he doesn’t want to do that anymore, nuts to him, because Jesus said so and this husband agreed. Unless something was really wrong at the start of the marriage, nullifying the contract, the contract binds. This husband then can go to the State and make the same request for release from marriage. The State will say, “Sure! You want out of that solemn contract, you get out of that contract,” because that’s the law right now. Guess which authority the court obeys? And which one the culture listens to? (The State’s megaphone is so powerful here that the Catholic Church now risks schism over the authority of an institution – civil marriage – that should not even exist.)

Under these circumstances, the very best the wronged wife can do to protect her family and her uxorial rights is to fight – at great expense – for a delay. When time runs out, after a year or two, she and their son are toast, stuck in the single motherhood-alimony-joint custody cycle (if she’s lucky!). This is worse today than before, because no-fault divorce refuses to even acknowledge the injustice done to the wife by her husband… but it has always been a problem, ever since the State asserted the authority to alter the terms of marriage contracts at its whimsy. The State has always ignored the plain terms of religious marriage contracts that exclude or limit divorce.

One esteemed scholar has written, rightly, that the legal regime of no-fault divorce is personally harmful to every person living under it. But he does not go far enough: any legal regime under which the State presumes to define, modify, or dissolve a marriage contract, over and against the terms of the contract as understood by the contracting parties at the time of its making and as taught by their Church, undermines the entire institution. Such a regime is personally harmful to all those who are stripped of the State’s robust defense of what ought to be – what once was – a private agreement that is publicly binding, and it leads inevitably to the disordering and decline of marriage precisely as it has played out during the past two centuries. Two years ago, I wrote that civil marriage is a public policy tool designed to attach children to intact families. I could not have been more wrong. In reality, civil marriage is a weapon against the family. It was designed to undermine the family by the cruelest of the French Revolutionaries, it was expected to undermine the family by the most conservative of Catholic popes, and, lo! It worked!

Once again, Pope Leo cuts to the heart of the matter:

Marriage was not instituted by the will of man, but, from the very beginning, by the authority and command of God; that it does not admit of plurality of wives or husbands; that Christ, the Author of the New Covenant, raised it from a rite of nature to be a sacrament, and gave to His Church legislative and judicial power with regard to the bond of union. On this point the very greatest care must be taken to instruct them, lest their minds should be led into error by the unsound conclusions of adversaries who desire that the Church should be deprived of that power. (Arcanum 39)

The Pope concedes an executive role for the State in marriage, but only in cooperation with the Church, and never usurping in any way the legislative and judicial authority which is absolutely excluded from the public sphere:

It is of the greatest consequence to husband and wife that all these things should be known and well understood by them, in order that they may conform to the laws of the State, if there be no objection on the part of the Church; for the Church wishes the effects of marriage to be guarded in all possible ways, and that no harm may come to the children. (Arcanum 40)

The separation of powers dictated here was ignored then, and has been forgotten today, even by conservatives. It was swept away in the great nineteenth-century race to secularize everything, and about the only people who take it seriously now are the vanishingly small sect of Catholic royalists. But I have come to believe that Pope Leo’s basic model is the only plausible way forward. (This shouldn’t be too surprising, since Pope Leo was only describing how marriage had worked for the past thousand years, and in most respects from the dawn of human history. It’s not like he was making it up.)

Of course, Pope Leo writes from a very narrow, Catholic-centric perspective. I mean, he’s the Pope, and particularly a Pope under siege – and, beyond that, he did not believe that other religions should, ideally, be allowed to exist (a position contradicted by later, infallible, Catholic teaching). Therefore, his concern was exclusively with Catholic marriage, and his model embraces Catholic marriage in a Catholic confessional state only. The marriages of Muslims, for example, are not even vaguely contemplated in Arcanum, because Muslims, in Pope Leo’s thinking, should not really be tolerated in the first place. But Pope Leo’s model for marriage has deeper roots than the Catholic confessional state, and, updated in light of the modern Catholic acceptance of religious diversity, his model can be extended far beyond Rome-State relations.

We can and should adopt – or, rather, revive – a legal model for marriage wherein its terms, especially with respect to children and parenting, are defined by the spouses (within common-law limits), normally (though not always) in consultation with their religious authorities. The State’s function in marriage would then be to enforce the contract, stepping in when it is breached, within limits defined by the contract itself.

A Catholic couple that wishes to marry should be able to vow lifelong marriage, consign juridic authority over the marriage from the State courts to the diocesan marriage tribunal (including all proceedings for annulment, absolute divorce, and divorce from bed and board), and rely on the State solely to enforce the judgements of that tribunal. A Jewish couple should be able to do the same, with the rabbinical system in place of the diocesan tribunal and the kettubah in place of the “lifelong vow”. A Muslim couple should be able to (clutch your pearls, Breitbart!), by mutual agreement, bind themselves to a distinctly Islamic understanding of marriage and to using the Islamic legal system in resolving marital and family disputes. The non-religious, or those who marry outside their religion, or whose religions do not have all this handled for them, should be capable of defining their own terms and rules of adjudication – as unchurched spouses have done since pagan times – and they ought to be able to depend on the State to enforce the terms of their marriages. (Presumably most evangelical Protestants will make marriage lifelong “except for adultery,” based on their misunderstanding of porneia in Matt 19, and so forth.)

This would require a fairly significant restructuring of American state and federal law, so much so that Jennifer Roback Morse calls it a “fantasy” with “exactly zero chance” of being enacted. But it is worth pointing out that Mrs. Morse says this in the context of her own argument for stopping same-sex marriage, repealing no-fault divorce, overturning Lawrence v. Texas, and restoring a child-centric model of State-controlled marriage that has not, in fact, ever existed, nor (as Pope Leo has argued and two centuries of consistent, constant experience have proved) ever could. While I concede there may be a universe where Mrs. Morse’s plan has a greater than zero chance of succeeding, it is the same universe where “The Moon’s A Window To Heaven” won the 1989 Grammy. My proposal, by contrast, stood for millennia before we capitulated to the radical redefinition of marriage in 1792. It’s a heavy lift, but it’s doable.

There are quite a few others out there who object to, or at least worry about, the idea of “getting the government out of marriage,” such as Maggie Gallagher, Robert George (again), Mollie Hemingway, Richard Epstein, the underrated Lydia McGrew, and (in subsequent pieces) Jennifer Roback Morse. They argue that completely eliminating government involvement in marriage is impossible in any world with sexual reproduction, and that even pretending to totally privatize marriage would lead to, as Gallagher puts it, “a gigantic expansion of state power and a vast increase in social disorder and human suffering.” They are right. Marriage is an institution with inherently public consequences, and the State will therefore always be an important stakeholder. I am not proposing that we “get the government out of marriage.”

But I propose that we stop pretending this particular stakeholder is more than it is. The State is not marriage’s owner. It cannot legislate marriage. It cannot intrude on, still less redefine or dissolve, a religious vow made by free citizens before their God. Yet we’ve spent not ten years, not fifty years, not a century, but two hundred twenty-three years pretending the State can do just that. We’ve submitted ourselves to its approval, paid its license costs, kowtowed to its courts, and declined to conduct sacramental weddings for those whom the State did not want married – even when the State’s decision was horrendously unjust. Let’s put the State back on the sidelines, where it belongs: enforcing the marriage contracts, not making them up.

For those of us who hold the “conjugal view” of marriage, there are some downsides to abolishing civil marriage: given our society, there is no doubt that some individuals in a post-civil-marriage world would make use of their newfound private license to make silly or unhealthy arrangements with others and demand that we call those relations “marriage”. Without the government sitting around playing umpire with everyone’s marriages, we would be powerless to stop this. But, since this already happens – and will be compelled by the State roughly five minutes from now anyway – it is tough to see what we lose by getting the State out of the marriage-definition (-and-compelling-everyone-to-agree-with-it) business. We will also be forced to rethink how the State approaches a few popular policies (like Social Security’s spousal benefits) which, under today’s law, depend on a single, State-defined, State-centric conception of marriage. However, as I have discussed before, we already have a moral obligation to revise these policies to protect people who depend on one another but are not eligible for civil marriage, and, fortunately, we also have powerful legal tools at our disposal for doing so, such as the reciprocal beneficiaries model.

There’s a big upside for the “conjugal” camp, too: if the traditional, natural-law understanding of marriage has any hope of survival and revival, it can only be with the destruction of civil marriage. As Pope Leo argued and as two centuries of continuous, consistent erosion of marriage have proved, there is no hope whatsoever that any human government can do anything but attack, undermine, and crowd out natural-law marriage at every turn. In history, wherever you find a thriving marriage culture, built on the natural law as reinforced by the words of Jesus Christ, there you (nearly always) will find a government that remains a respectful distance from the private and religious spheres where those marriages are defined and administered. I do not pretend that abolishing civil marriage will restore a natural-law understanding of marriage to the culture overnight (too much damage has been done, and too many once-great religions, like the Anglicans, have forgotten this tradition), nor could such a restoration come about without uncoerced mass conversions, but ending the hostile influence of human government on marriage – giving up, once and for all, the conservative fantasy that we can harness the power of government in service of the supernatural end of protecting natural marriage – is a necessary first step in restoring cultural esteem, civic support, and religious authority to the institution of marriage.

We conservatives often seem to be the only ones who realize that the growing disorders of marriage threaten not just the immediate victims, but the rest of us too. We have poured time and treasure beyond count into shoring up the institution of civil marriage, trying to stanch the bleeding as our culture and civil society collapse around us (leaving only the State as the organizing principle of all society). But civil marriage is one of the causes of our problems, not their solution. Civil marriage was born in the bloody orgies of the French Revolution precisely to redefine marriage as the State may please. Where so much of the Revolution failed, here the Jacobins triumphed, handing their legacy down to the modern Left as they did so much else. In just two centuries, conservatives and progressives alike have come to see marriage as firstly a government concern. Civil marriage has been in decline since the day it was invented, its definition growing steadily out of control, far beyond any rational meaning, secular or sacramental – as it must, as long as the government owns it. It has dragged society along with, its fraying causing our culture to disintegrate.

Civil marriage has now entered its terminal phase: it is impossible to imagine the state of marriage getting much worse, because, on most of the metrics we’ve discussed, it is mathematically impossible for the state of marriage to get meaningfully worse. It’s over. It’s been over, since long before gay marriage was legal in a single state – probably since before Andrew Sullivan launched the modern gay marriage movement. Civil marriage is dead.

And it deserved to die.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The proposals made in this piece are a radical departure from pretty much anything familiar in contemporary American politics. I had a great deal of trouble articulating them at all – you should see all the discarded drafts! – and I still worry that I was unclear at certain points. If you have questions, or want clarifications, on what this article is saying – or just want to debate my interpretation of Pope Leo XIII – please use the comment boxes below. I will do my best to respond, and, if warranted, will post a follow-up article clarifying anything that turned out to be especially unclear (or especially wrong-headed).

FOOTNOTES

†† By sheer coincidence, the Supreme Court actually issued this ruling while I was working on the final revisions to this piece today. I’ve been working on it for over a year – researching, circulating drafts, throwing drafts away – but I suppose it’s lucky that I finally got it finished on the exact day when “civil marriage” is on everybody’s mind. I am happy to note that everything I predicted about the decision has been confirmed in just the past few hours since it came out.

* Though I am going to disagree with Robert George’s position on marriage law in this post, I want to make clear that I still hold him personally in the highest esteem. Normally, I would consider it unnecessary to make note of this – obviously, I can disagree with a guy while still acknowledging he’s precisely eleven times smarter than I am and a good man to boot – but, in the marriage debate, there has been an unsettling tendency for all political disagreement to become intensely personal, and for those abandoning the marriage traditionalists to simultaneously disavow their prior associations with their erstwhile allies. So let me be clear: I’d vote for Robert P. George for president, given half a chance. If he’s ever in the Twin Cities area, he has a standing invitation to my place a bowl of my famous pasta carbonara and some rousing company (on the off chance you’re reading this, Dr. George, we have some shared Facebook friends; you can get in touch with me through them). And, for what it’s worth, although I now think he’s wrong about how the law should interact with marriage, George’s understanding of marriage as a natural conjugal union remains absolutely correct, as does 99% of his famous paper on the subject.

† Although Catholics do not consider Arcanum an infallible papal document, we are nevertheless obliged to give very serious thought to situations where we find ourselves disagreeing with a Pope in a major document like an encyclical. I did not have to reconcile my position to Arcanum as a matter of religious doctrine, but it made me very uncomfortable that I could not easily do so.

+ Blackstone does write of two kinds of “divorce”, but neither is what we understand to be “divorce” today. His “divorce from the bond of matrimony” is known today as “annulment”, and his “divorce from bed and board” is known as “legal separation”.

** Except for the Jews, who only promised to be free, faithful, and fruitful – not necessarily forever. Still a damn sight more than the “vows” at civil weddings today.

‡ A few online sources give 9 November 1791 as the date for the French creation of civil marriage, but I can’t find any substantiation for that claim. Suzanne Desan’s book The Family on Trial in Revolutionary France actually gives two dates that are relevant to our inquiry here: the adoption, on 27 August 1791, of the Constitution of 1791, which stated that the State viewed marriage as merely a “civil contract”; and the passage of legislation, on 20 September 1792, which actually made the State the minister of marriage through the laicization of civil record-keeping. I focus on the second date. Many governments have viewed marriage as a civil contract, before and since, but left it to citizens to actually define and perform it. It is the French decision to absorb marriage into the State through laicization which, in my view, marks the invention of civil marriage. While I’m in a footnote, I think it’s worth mentioning that there was some precedent for the French decision of 1792: in the Edict of Versailles, issued by King Louis XVI in 1787, the French had begun allowing civil magistrates to recognize Protestant marriages, without actually acknowledging that a Protestant marriage had occurred – the recognition became, in law, the marriage. This mess arose because the regime did not feel it could knowingly cooperate with, or give effect to, Protestant sacraments, but their awkward solution provided a civil-esque model for marriage, which the revolutionaries extended five years later into the marriage regime that has more or less prevailed ever since. This reinforces a point I made earlier: The history of marriage is nothing if not complicated, and nobody should walk away from this piece thinking that there’s a single, simple narrative that describes how marriage has been understood throughout history.

§ The reader may expect me to include “…and the State tried to ban interracial marriage!” in this litany of evils. The reason I didn’t is because anti-miscegenation laws predate civil marriage: Americans invented them (or, at least, their modern incarnation) over a century earlier. During King Louis’s flirtations with taking over marriage in the 1770s (mentioned in the previous footnote), the French ancien regime tried on a little racist interference in marriage, as well. This was abominable, but not something I can blame on the Jacobin Club – not something caused by the State takeover of marriage. As Pope Leo pointed out earlier in this post (Arcanum 26), the government has often, throughout history, interfered with the legality or validity of marriage, always to marriage’s detriment. Racist marriage laws are a good example of that. The French Revolution transformed marriage into a State function, dealing far more serious and lasting damage than prior transgressions, but it was hardly the first offense against the sanctity of marriage in the history of the world.

¶ And there is a great deal of truth in it. The public interest in marriage is as obvious as the practical benefits for its participants. It is obvious to Dr. Heaney, obvious to Justice Petersen and the Supreme Court, and I made a pretty decent case for it two years ago. Again: I am not arguing that marriage is unimportant to individuals or society. I am arguing that the way we have (recently) tried to protect it, by ceding authority over it to government, is an inappropriate and recent overreach that is actually destructive, in several different ways, to natural-law marriage. I continue to agree with Dr. Heaney on all the important philosophical points, and my carbonara invitation to Dr. George certainly includes him. Also, in the interest of full disclosure, I’ll admit for those who didn’t get it from the name that he is my father. (Dr. Heaney, that is, not Dr. George.)

Test comment!

You should summarize your points in a new post, limited to 800 words if you want to influence the debate more effectively.

Fair and true. I didn’t really expect to have much influence — nobody reads my blog — but it is getting some readers (weird!), so I guess the TL;DR version is due.

Nah. A person’s essay should be as long as they care for it to be, as long as it has content the entire time. One of the problems with modern debate is that its been reduced to the snippet level, and therefore is devoid of content.

Is it possible for Catholics to draw up a prenup (or some other sort of weird-sex-contract) that would bind them to being sacramentally married in the eyes of the US Gov’t?

I don’t *think* so.

Partly that’s because my read of the marriage laws says “no.” Looking just at Minnesota, the statute on prenuptial agreements (Minnesota Statutes 519.11) only contemplates prenups being used to help divide property after the dissolution of a marriage, and the statute on divorce (518.06) is pretty darned final: “Defenses to divorce are abolished.”

Partly that’s because I’ve never heard of anyone doing it, and because (in other states) they have had to push for legislatures to enact “covenant marriage” in order to achieve something similar, and I don’t imagine they would do that if they could achieve it through a prenup.

But I’m not as convinced by either of these arguments as I’d like to be, so I’m going to leave it at “I don’t THINK so” and ask a lawyer next time I manage to corner one.

The answer would be no as its not possible to write a contract requiring the government to recognize something that it hasn’t already bound itself to recognize. So, a person can’t require the government to recognize the sacramental nature of a marriage.

Nor would that achieve much anyhow. As a sacramental marriage is just that, the recognition of it, or not, by the government wouldn’t add to it.

Interesting. I have read another article that takes the same position. That marriage would actually be strengthened by taking it out of government control which has made in a perfunctory contract to regulate property more than seeing it as the place where children are propagated, raised and nurtured, to create an orderly society. With the recent ruling by the Supreme Court Congressman King of Iowa suggests that we take it out of the civil courts altogether.

I must disagree – civil marriage must survive, even if now is in crisis; civil marriage is part of whole civic system of modern society, this strong civil society – civilizational society, immanent; it is effect of the long road of history and conservatives cannot reject this road; represent by you way of thinking is one of basic fault in conservative mind, it says that conservatives should be against modern society and back beyond “mistakes” when everything were good, but conservatives should not conserve particular things, thoughts, symbols, norms and values but process of organic changing of society and culture, for me this process goes from “top” to “down”, in Europe (and America also) from Christianity, transcendental sphere to secular, civil and humanist society – concept of human rights goes from Christianity to secular society, things which in past needed religious references become independent, conservatives should only try to maintain this bound between religion (metaphysics) and society, but religion cannot be dictator of society (otherwise it’s become ideology), liberals try to cut this bound, and leftists create “new religion” – conservatives prevent whole structure of world: its religion (and metaphysic philosophy) and secular (political) part. You are close to create conservative utopia, “we conservatives will close themselves in religious tower where everything has its right place” and liberals and leftists may take “their civil society”. If now conservatives loose it’s mean they conserve in bad way, and must once again proceed to connect civil society with metaphysic essence, even if one it’s guerilla’s war.

This is a view that I’ve found appealing for some time, but have struggled to conceptualise or lay-out in as clear and cohesive a fashion. Thanks!

This is like reading 800 pages about the buggywhip or steam engine.

In what way?

It’s long, it’s dull and it addresses and obsolete thing, once relevant in an earlier era, but pertinent no more.

You mean that *marriage* is irrelevant?

Yes

Oh, okay. Fair enough.

I’m curious: why’d you read it, then? I mean, it was pretty clear from the outset that it was a really long post about marriage. That’s interesting to lots of people, but if you start off thinking marriage is obsolete, I can’t see how that could have ended well.

I’ve spent time in museums and antique shops …. it’s kind of the same.