A couple of days ago, I mentioned offhandedly that “originalism” and “textualism” are not the same thing. Then I moved on. A couple of readers have asked me to expand on this. What’s the difference between an originalist and a textualist?

I’ll start with a brief history, then the formal differences, and then a word on common usage… because, in common usage, “originalism” and “textualism” are pretty much interchangeable. I’ll explain why that is, and why it’s not a problem as long as you know what’s going on.

In the 1960s and 1970s, there was growing disconnect between what the Constitution seemed to say, what everyone had always thought the Constitution meant, and what judges were suddenly saying the Constitution actually meant.

For example, for two hundred years, public schools in various parts of the country held Protestant prayers prior to the start of classes; nobody ever considered this a violation of the Establishment Clause. Then, suddenly, in 1962, the Supreme Court’s Engel v. Vitale struck down school prayer and imposed a radically enlarged Establishment Clause on the country. This, at least, was a plausible interpretation of the Constitution — which does, after all, expressly forbid the establishment of any religion — but, as the ’60s became the ’70s, court rulings became increasingly untethered from any clear connection to the text of the Constitution or other laws.

The “one person, one vote” doctrine was invented out of thin air in a bizarre 1964 case on redistricting, despite the fact that the existence of the U.S. Senate explicitly refutes the doctrine. The Miranda warning was a great development in criminal law, but it was passed into law not by lawmakers, but by judges. In the 1970s, the Supreme Court imposed a “moratorium” on capital punishment by judicial fiat. Most controversially, a whole body of decisions from Griswold to Roe to Casey created a right to so-called “sexual privacy,” using rationales that were totally divorced from the text of the Constitution — and, increasingly, from rationales used in prior cases as well! (Good luck trying to use the “sacred marital bed” rationale from Griswold to explain Eisenstadt or Lawrence!)

There came to be a sense in parts of the legal profession–especially conservative parts–that judges had subtly shifted from applying laws passed through the democratic process to inventing whatever laws they (the judges) happened to like and finding vague legal-sounding rationales for it after the fact. This, obviously, undermined the basic structure of our Republic, since laws are supposed to be created by elected officials through a complex series of checks and balances, not handed down at the whim of five unelected old men in black robes. So, the thinking went, the judiciary needed to find a way to tether itself to some kind of principle outside its own whims. The judicial branch had to be bound, in some way, by the laws that had been passed democratically.

(UPDATE: It’s worth at least skimming Robert Bork’s 1971 paper, “Neutral Principles and Some First Amendment Problems,” which articulated the problem, why it was a very serious problem, and offered some of the very earliest suggestions for how the problem might be solved in accordance with the assumptions of our constitutional order.)

An early attempt at solving the problem was called “originalism.” (It’s now sometimes called “old originalism.”) The idea here was that judges should interpret laws, especially the Constitution, according to the original intent of the framers. So, for an originalist, the judge’s job in, say, a free speech case is to get into James Madison’s head and ask, “If James Madison were judging this case, would he consider this speech something that should be protected by law, or no?” You determined what the author of the law intended, and then you ruled according to that intention.

This theory became popular in the 1970s and 1980s, and reached its apex when President Reagan’s Attorney General, Edwin Meese, preached it in a historic 1985 speech to the American Bar Association. Original intent theory accomplished a lot of what it set out to do: it did tie originalist judges to the democratic process in a way that they mostly just weren’t in the 1960s and 1970s. It did make judicial rulings more predictable and less politics-driven. It did reaffirm the Constitution’s claim that the laws of the United States — not the opinions of judges — are “the supreme Law of the Land.”

However, even as Attorney General Meese was giving that speech to the ABA, original-intent theory was being critiqued in the legal profession, and a new faction had developed within originalism in response to those criticisms. There were three basic problems with originalism’s “original intent” approach:

PROBLEM #1: Originalism requires judges to determine the intent of the law’s author. But most laws have many authors! James Madison may have drafted the First Amendment, but he wasn’t the only contributor, and he sure wasn’t the only person involved in making it law. It is almost certainly the case that there were different views of the First Amendment among different legislators who voted for it. James Madison might consider a particular work to be free speech, while Thomas Jefferson might disagree, and Alexander Hamilton would probably have yet another view. And there were dozens of committees and conventions involved in drafting, passing, and ratifying the Constitution. Not all of them seemed to even fully understand what they were voting for, precisely. Some people voted the way they did because their political allies told them to. Under originalism, what do you do when the original intent of the framers are in conflict? Whose intent counts?

(It’s worse than that, if you really go down the rabbit hole: How many federal laws do you think our legislators today actually read all the way through? Can they really have an “intent” without ever reading the law?)

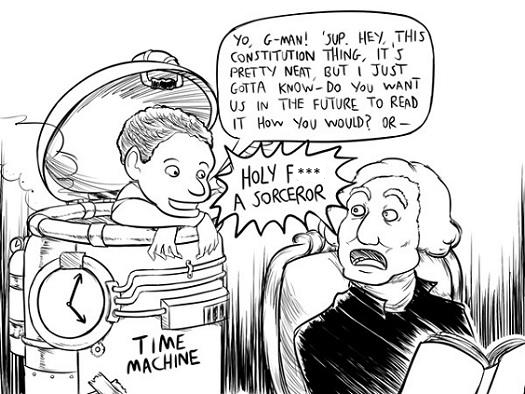

PROBLEM #2: Even if you could identify whose intent should count, how on Earth would you identify what the intent is? Judges aren’t mind-readers, and they aren’t spiritual mediums. What would Thomas Jefferson say about free speech on blogs? What would Alexander Hamilton say about warrantless surveillance of cell phone signals? Unless you know how to conduct a séance where you can ask them, there’s nothing you can do except go with your gut feeling about how the Founder’s “should” want the case to turn out. And the whole point of this exercise was to tether judges to the rule of law instead of their gut feelings about how cases “should” turn out.

PROBLEM #3: The intent of the lawgiver does not always line up with the text of the law. This is an extreme example, but take Title VII, the law that forbids discrimination on the basis of race, sex, and religion in employment. The original draft of the bill did not include protection against sex discrimination. A Congressman who supported employment discrimination (on the basis of both race and sex) was trying to stop the bill, so he added “sex” to the text as a “poison pill,” because he thought it would make enough Congressmen to change their votes to kill the bill. So the “original intent” of the anti-sex-discrimination clause in Title VII is… the protection of racial discrimination?

Textualism (sometimes called “new originalism”) was a revision of originalism designed to answer these criticisms. This newer method set aside original intent, and instead focused on original public meaning of legal texts: the way an informed member of the general public would have understood the law at the time it was passed. This refinement eliminated the need for mind-reading, and it eliminated the need to deal with conflicts between lawmakers with different intents. Justice Antonin Scalia used these refinements to (mostly) bring an end to the era where the Supreme Court would spend weeks poring over legislative drafting history trying to figure out what lawmakers intended to do, rather than figuring out what they actually did by enacting the law that they enacted.

Textualism still requires a great deal of historical research, because it is not always clear to us today what the public of, say, 1864 understood by the phrase “privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states”; history, including drafting history, can provide evidence for the common meaning of those phrases. Textualism also requires careful parsing of the text of the statute. Textualists can reach the end of an honest textual analysis and still completely disagree on the correct interpretation, as Amy Coney Barrett explained in her 2018 Canary Lecture… and as Justices Alito and Gorsuch (both textualists!) showed in their bitterly conflicting opinions in 2020’s Bostock v. Clayton County case. And textualism can even be hijacked by determined “judicial activists” who distort or exaggerate the original public meaning to reach a predetermined conclusion. Textualism does not solve all problems of judicial interpretation.

But textualism is a much stronger theory than “old originalism.” Since the 1980s, original-intent theory (“originalism”) has now been almost totally supplanted by original-meaning theory (” textualism”). There are still a few original-intent theorists out there, with their own ways of dealing with the problems described above… but those theorists are marginalized.

As a result, “textualism” and “originalism” are often used interchangeably today. Many textualists see their version of originalism as the “true” originalism. Justice Antonin Scalia was undoubtedly America’s most important textualist and led the charge to smash the errors of originalism — yet he identified himself as an originalist until the day he died. Judge Amy Coney Barrett, recently nominated to the Supreme Court, switches between the two terms in different papers of hers — sometimes several times in the same paper. So if someone walks up to you on the street and says, “Hello, I’m a federal judge, and I subscribe to originalist theory,” first, get an interview, but, second, you should assume she means original-meaning textualist theory, not the old-originalist original-intent theory.

Why does this matter? Because there’s still a good deal of confusion about what modern self-identified originalists believe. To this day, I routinely read and hear criticisms of original-meaning textualism (sometimes from prominent lawyers) about how textualism can’t work because it relies on “mind-reading.” This is because the speaker made up his mind about “originalism” in 1982 and thinks modern textualism is exactly the same thing.

In my opinion, textualism is also clearly superior to its main modern competition, the “living Constitution” theory that was more dominant during the 1960s and 1970s. Nor am I alone in that assessment. As Justice Elena Kagan said in 2015:

The truth of the matter is you wake up in a hundred years and most people are not going to know most of our names. But I think that that is really not the case with Justice Scalia, who I think is going to go down

as one of the most important, most historic figures in the court.

And there are a whole number of reasons for that, which– this is about statutes, so let’s just– but I think the primary reason for that is that Justice Scalia has taught everybody how to do statutory interpretation differently.And I really do mean pretty much taught everybody. There’s that classic phrase that “we’re all realists now”? Well, I think we’re all textualists now, in a way that just was not remotely true when Justice Scalia joins the bench.

With the deaths of Justices William Brennan and, later, Justice John Paul Stevens, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, inherited leadership of America’s “living Constitution” movement. With her death, there is no clear heir to carry that philosophy forward on the Supreme Court. Whether you call this interpretive theory “textualism,” “new originalism,” or just “originalism,” it seems to have been largely absorbed into the legal mainstream, even as it remains coded as a “conservative thing” for many observers. We are all textualists now.

And, as Bostock showed, textualism does not necessarily always yield results conservatives like.

P.S. “Originalism” is also sometimes presented as if it were a subset of “textualism.” In this perspective, textualism is the general theory, and originalism is how that theory is applied to the U.S. Constitution. This conception came about largely because of a theory on the non-textualist side of the bench that statutes and constitutions should be interpreted in fundamentally different ways. (This theory is the actual law of the land in Canada.) However, most practicing textualists reject the idea that constitutions and statutes are to be read in fundamentally different ways, and thus reject the notion that originalism is simply textualism applied to the Constitution. Judge Amy Coney Barrett explains why textualists reject this in her Canary Lecture, which I linked earlier.