(UPDATE: This whole post was secretly just preparation for my interview with FCC Commissioner Nathan Simington a couple weeks later.)

(TW: net neutrality, pasta racism, NCTA v. Brand X, brief but alarmingly favorable quotation of Justice Breyer, Ted Stevens Dance Remix)

Over on Facebook, some of my friends have asked me to give an update to my 2014 post(s) which laid out a conservative argument for Title II “common carrier” regulation of Internet Service Providers.

But, honestly, not all that much has changed. Title II was imposed soon after I called for it, albeit in a limited and, in some respects, sloppy fashion. It remained in effect until 2018, when the Trump-era FCC repealed it… but the repeal itself got caught up in a legal battle (Mozilla v. FCC) which was only finally resolved in July 2020, when Mozilla decided not to appeal. That left about four months for telecoms to go wild with their newfound freedom to throttle.

Then came the presidential election. With President Biden’s victory came the inevitability of new Title II regulation. Telecoms are now right back on their best behavior, hoping to convince the FCC that they are good little boys and girls and will not put any more firefighters’ lives up for ransom, so the mean old FCC won’t ban zero-rating.

(ASIDE: I’m not really convinced the Verizon firefighter thing was a net neutrality issue, as some have argued, but it was terrible press and at least points to monopoly-like behavior at Verizon. By “monopoly-like,” I mean that only a monopolist or a fool would so abuse a sympathetic, expensive customer during a nationally-televised emergency. I don’t think Verizon is a fool.)

So net neutrality critics have been saying that “we ended net neutrality and the Internet didn’t end,” which is half-true: no, the Internet didn’t end… but, as I noted shortly after the litigation began, net neutrality never really ended, either.

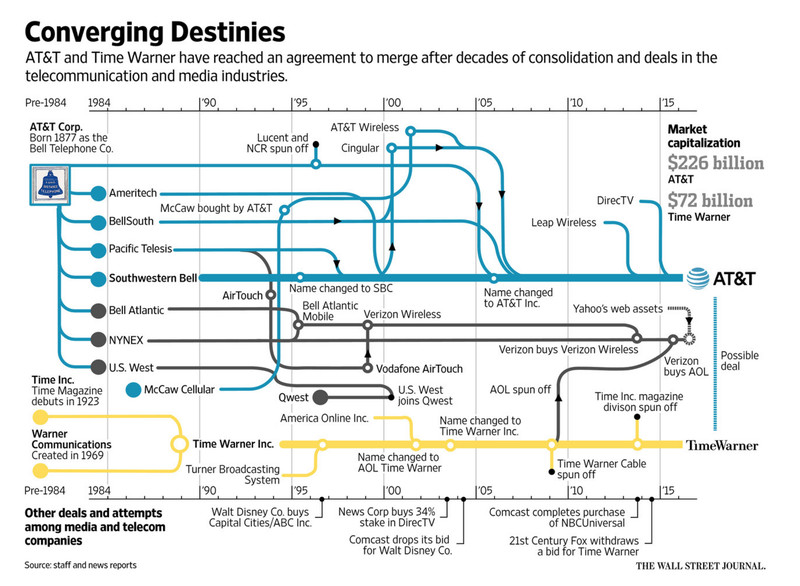

Meanwhile, there have been no grand market disruptions that would tend to change my 2014 analysis. Telecom consolidation has continued apace, as mainstream economic theory predicted, because, as I explained in 2014, telecoms are natural monopolies.

There are still exactly two wired broadband competitors in my zip code (Comcast and CenturyLink). I’ve lived in four homes since 2011, and they were the only two options at all of them.

I only have bills back to 2015, but it looks like I personally pay almost exactly the same amount of money to Comcast ($60 now vs $65 then) for a lower tier of service (Performance Pro+ vs Blast), but that lower tier is apparently just as fast as what I had in 2015 (150mbps vs 150mbps), and inflation exists, so I’m overall in slightly better shape. I only have to call their customer service once a year to lock in a discount (I didn’t used to have to do that, sigh), so, on the whole, I hate Comcast much less than I did in 2014, right after I moved twice and had to spend days on their support line.

So: no news! You can reread my 2014 net neutrality post; I pretty much stand by it. (There’s a couple details I wish I could retract, not because I think I was wrong, but because I didn’t present enough evidence. C’est la vie.)

However, while I was rereading everything that’s happened since 2014, I was reminded of something: Republican FCC commissioners really confuse me. They’re Republicans, they grew up in the same conservative movement I did, confirmed by Republican senators I generally trust, and I really like to think that they are doing their best to follow the law and help American voters. Yet Republican FCC commissioners routinely say things that—it seems to me—clearly aren’t true, and make arguments that—it seems to me—don’t make sense. There were times during the Trump Administration when I wanted to grab Chairmain Pai (who is a super-nice guy, by all accounts) by the shoulders and shake him while shouting questions in all capital letters.

If I ever had a chance to sit down with a Republican FCC commissioner, and time were no object, and he (or she! you never know) didn’t throw a coffee in my face after the first few questions, these are the questions I would have—sans caps lock:

QUESTIONS OF TEXT AND HISTORY

As a conservative, before I talk about public policy, it’s for me important to understand how the public policy evolved, why it did so, and what the governing law means. This matters both because I’m an originalist-textualist disciple of the Federalist Society and because I’m a Chesterton’s Fence conservative. Republican FCC commissioners consistently have what I perceive as bizarre views on the text and history of net neutrality, and their seemingly erroneous conclusions inform the rest of their analysis.

1. Why do Republican commissioners consistently act as though net neutrality regulation of telecoms were unusual?

Telecoms who own the Internet’s physical network (originally including cable telecoms; see, e.g., AT&T v. Portland) were regulated directly as Title II common carriers from the unveiling of the first public ISP in 1989 until 2002, when the FCC launched its experiment in deregulating cable broadband by classifying the physical-network providers as “information services,” not “telecommunications services” in the Cable Modem Order. (Telecommunications services are subject to Title II common carriage rules; information services are not.)

During the 2007 Sandvine controversy, the FCC asserted power to enforce net neutrality against information services. Comcast resisted, leading to a lawsuit. The FCC lost, triggering a second attempt to enforce net neutrality (without common carrier regulation), leading to another lawsuit, which the FCC also lost. The FCC more or less enforced net neutrality the entire time, even though the courts kept striking down its legal justifications for doing so, although some bad stuff like the Netflix stickup snuck through in the chaos.

This finally ended in 2014, when the courts straight-up told the FCC it could only continue requiring telecoms to follow net neutrality if they were regulated as Title II common carriers. The FCC agreed and soon imposed Title II common carriage in the Title II Order. That lasted until 2018’s Restoring Internet Freedom Order (aka RIFO), when, for the first time in at least a decade, the FCC gave up on trying to enforce net neutrality.

So net neutrality was consistently the law of the land from 1989 to 2002, then again from 2007 to 2018. That’s 24 of the 32 years that ISPs have existed. 16 of those years were under Title II regulation, and 13 of them were under full-blown “heavy touch” Title II! (The other years, 2007-2015, were regulated under successive pseudo-Title II regimes which turned out to be illegal.)

That analysis doesn’t even consider the way ongoing litigation in NCTA v Brand X and Mozilla v. FCC affected the regulatory landscape. In fact, it seems those lawsuits, which ran from 2002-2005 and 2018-2020, created enough uncertainty to keep ISPs from pressing their advantage. Furthermore, state-level net neutrality legislation sprang up in the waning 2010s, which further complicated matters for ISPs even after Mozilla concluded!

So physical network owners were truly free of net neutrality regulation for only about two years in the late 2000s and a few months before President Biden took office.

Yet, every time someone suggests imposing net neutrality rules—still less through Title II—Republican commissioners (egged on by the Wall Street Journal) deride it as a revolutionary overthrow of all prior precedent. They insist that “the internet thrived for decades under the light-touch regulatory regime” (RIFO 109), even though that regime only actually existed for a few years in the mid-2000s. In reality, the 2002 Cable Modem Order and RIFO were the revolutions. Much of the most explosive growth of the Internet took place under full-bore Title II regulation. Do Republican commissioners genuinely dispute this?

2. Why do Republican commissioners think the Stevens Report and Universal Service Order support their view of telecommunications services?

Republican commissioners routinely cite the Universal Service Order (1997) and especially the Stevens Report (1998) as supporting their view that “Internet Service Providers” are providing “information services,” not “telecommunications services.” RIFO relied heavily on the Stevens Report. But the traditional ISPs discussed in Stevens and Universal bear almost no resemblance to modern ISPs.

Traditional ISPs, as you will remember if you were a nerd in the ’90s (but as the Stevens Report carefully explains if you weren’t) did not own any telecom infrastructure. Instead, they provided Internet access to consumers by using established telecom infrastructure. They would acquire this infrastructure through leasing or unbundling agreements, all of which only happened because the telecoms were regulated under Title II. (Stevens Report, 66-67, 81, etc.) These traditional ISPs were subject to strong competitive forces, because basically anyone could start a traditional ISP. (Including, I hear, former Chairman Pai’s college roommate! Good for him!)

Traditional ISPs were almost wiped out in the wake of the FCC’s 2002 Cable Modem Order, which exempted cable from Title II regulations. Traditional ISPs depended on those regulations to access consumers. (That’s what the Brand X case was all about!) Like many of the few surviving traditional ISPs, Brand X today sells low-speed access over legacy Title II infrastructure—because the 2002 FCC and the Brand X case locked traditional ISPs out of modern broadband.

Modern ISPs— Cox, Comcast, CenturyLink, that lot—are all providing Internet access over a telecommunications network that they own. Provision of that telecommunications capacity is, unsurprisingly, a separate telecommunications service, according to both the Stevens Report (15, et. al.) and the Universal Service Order (789, et. al.). These documents balk very slightly at times when discussing (what were, at the time) novelties, like companies offering transmission and internet access in one package… but their underlying analysis is clear, and RIFO tries to drive a Mack truck through those cracks. (RIFO 57 is egregious.)

The modern FCC claims that, because Comcast may provide you with an email address, a personal webpage, and a DNS server on top of the vast and expensive physical telecommunications infrastructure you’re actually paying them for, that email address transforms Comcast’s entire service offering from a telecommunications service to an information service (e.g., Cable Modem Order, 38). The Stevens Report is particularly skeptical of this modern FCC argument: “It is plain, for example, that an incumbent local exchange carrier cannot escape Title II regulation of its residential local exchange service simply by packaging that service with voice mail.” (Stevens, 60)

This goes right to the heart of the issue: if modern ISPs merely provided an information service (as traditional ISPs did), then Title II regulation would have nothing to do with physical infrastructure investment, because traditional ISPs did not provide physical infrastructure. Traditional ISP profits did not directly go toward expanding physical infrastructure, but rather to what the FCC once called “enhanced services.”

The fact that so much discussion of net neutrality does revolve around whether regulation will dampen modern ISPs’ investment in physical telecommunications facilities demonstrates that modern ISPs are providing telecommunications services, within the meaning of the Telecommunication Act of 1996, as understood by the 1998 FCC! Do Republican FCC commissioners simply not recognize the difference between the ISPs discussed in the Stevens Report and ISPs today, or do they think the difference is somehow not relevant?

3. Why do Republican commissioners only invoke the “major questions” doctrine against attempts to impose Title II regulation, never against attempts to repeal it?

The “major questions” doctrine, cited by then-Judge Kavanaugh in U.S. Telecom and later by Commissioner O’Rielly in his statement accompanying RIFO (starts on page 525), is a judicial doctrine that, if Congress has not given an agency clear authority to issue rules of “vast economic and political significance,” the agency may not do so. Kavanaugh and and O’Rielly both think the 2015 Title II Order is vastly significant, and I agree.

But, if the 2015 Title II Order was a major rule, wasn’t the 2002 Cable Modem Order a much bigger major rule? The 2002 order blew up the Title II common carriage framework that had governed the Internet for over a decade. (It also governed primitive online activity, like BBS’s, going all the way back to the early ’80s, under Computer II.) It was a framework which Congress certainly appeared to be reaffirming in the Telecommunications Act of 1996, one that Congress had used for extremely similar telecommunications activity since the Great Depression.

And the FCC just… threw that entire framework in the trash in 2002, with zero clear authority to do so. That opened not just the Pandora’s box of net neutrality (it is no coincidence that Tim Wu coined the phrase less than a year after the Cable Modem Order), but, as we’ve seen, it helped fuel the marginalization of traditional ISPs.

If the major rules doctrine precludes major FCC action on internet regulation, then surely that doctrine not only allows but requires the FCC to abandon its 2002 experiment in deregulation and return to the status quo ante bellum: full Title II regulation, without forbearance, of all telecoms, even when those telecoms also provide internet access.

Somehow the Republican commissioners never carry their argument out to that logical conclusion. Why not?

(I get why the progressives never bring this up: they don’t like the major rules doctrine, because they don’t like agency restraint, because, in general, they don’t like separation of powers. But conservatives are supposed to be the rule-of-law folks in the room, and we look like opportunists!)

4. Why do conservative commissioners work so hard to ignore the original public meaning of the Telecommunications Act of 1996? Aren’t we textualists? Didn’t Republicans spend three decades taking over the courts and “the swamp” in order to put a stop to agencies (who think they know better) usurping the role of Congress?

Pre-1996, everyone knew how Title II worked: the owners of physical telecommunications infrastructure were common carriers, just like airplanes and electric utilities. People who provided services over that physical infrastructure—services like 411, and dial-up BBSs—were not. The Computer II Inquiry affirmed this dichotomy and tried, somewhat imperfectly, to define it in words.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 did not suggest that Congress wanted to rethink this basic regulatory regime, and, as we’ve seen, the FCC did not initially contemplate doing so. Traditional ISPs like EarthLink and online content providers like AltaVista were services; the telecoms who owned and operated the physical wires connecting them to consumers were common carriers. Indeed, it does not appear to have crossed the FCC’s mind to exclude any physical infrastructure owners from Title II common carriage rules until the 2002 Cable Modem Order was in the works.

The obvious, plain-English interpretation of the 1996 Act (particularly 47 USC 153 (50-53)) would hold that Comcast, CenturyLink, and the like are telecommunications providers and therefore must be regulated as common carriers. Ask the man in the street whether Comcast Xfinity is a telecom service and (after the initial, “Huh? Who are you? Is this a hidden-camera bit?”), the answer is going to be “Duh, yeah.”

Now, yes, sometimes the public is confused about subtle technicalities in the law, so maybe they’re mistaken about the original public meaning of the Telecommunications Act… but, on this, the common man’s interpretation aligns perfectly with the people whose job it is to suss out subtle technicalities in the law: judges.

To my knowledge, every appeals court judge who has ever looked at the Telecommunications Act of 1996—with the solitary exception of Judge Brown in U.S. Telecom—has agreed that the most natural reading of the Act of 1996 would classify physical infrastructure owners, like Comcast, as telecommunications providers, regulated as common carriers. That’s what Judges Leavy, Fernandez, and Thomas held unanimously in City of Portland (2000), it’s what Cudahy, O’Scannlain, and (again) Thomas held again in Brand X at the 9th circuit (2001), it’s what now-Attorney General Garland appeared to hold in U.S. Telecom (2017), along with Judges Henderson, Rogers, Tatel, Griffith, Srinivasan, Millett, Pillard, and Wilkins. (Now-Justice Kavanaugh avoided the question in his dissent.) Millett and Wilkins were explicit in their 2019 concurrences in Mozilla. Tellingly, in Brand X, the Supreme Court unanimously agreed to “leave untouched” the Portland court’s conclusion that this was the “best reading” of the statute, even as the majority deferred to the FCC’s alternative interpretation. Meanwhile, Justice Scalia wrote a scathing dissent insisting that the Portland reading was the only reasonable reading and that the Court’s deference to the FCC had gone too far.

Since then, Scalia’s classic dissent has gained considerable force in conservative legal thought. Justice Gorsuch rose to fame partly because of a devastating concurrence (starts on page 15) where he dismantled not only Brand X, but the Chevron doctrine on which Brand X rests. Justice Thomas, who actually wrote the Brand X majority opinion, recently recanted, in Baldwin v. United States (2020). Thomas wrote that his own opinion in Brand X now “appears to be inconsistent with the Constitution, the Administrative Procedures Act, and traditional tools of statutory interpretation.”

In nearly every other context, both in the judiciary and in political circles, Republicans today generally regard Brand X as a paradigmatic case of executive overreach that undermined the separation of powers, and Chevron in general as a problem. (Here, for example, Randolph May of the Free State Foundation cheers for what he expects to be Justice Barrett’s narrowing of Chevron and Brand X.)

Except for Republican FCC commissioners, who continue to trot out their contorted interpretation of the statute, an interpretation Justice Breyer (who upheld it) called “just barely” plausible. They continue to cite Brand X‘s anti-textualist, pro-agency majority opinion as a justification for doing so. As I wrote last year, you can sum up pages 10 to 40 of RIFO as “nanny-nanny pooh pooh Brand X says we can” and lose surprisingly little of substance.

I grant that Brand X has not been overturned and is therefore still technically “good law.” But isn’t it embarrassing for conservative commissioners to defend the Cable Modem Order‘s transparent executive-branch power grab? Isn’t it a bummer to have to justify it with Brand X, a decision fellow conservative judges and lawyers increasingly recognize as corrosive? Shouldn’t our people on the FCC be the guys insisting on following the original public meaning of the Telecommunications Act, not the guys trying to evade it?

I just don’t want to be a hypocrite when I criticize Secretary Xavier Becerra (a bloodthirsty, lawless cretin) for evading statutes that he doesn’t like, too.

5. When you get right down to it… do Republican commissioners on the FCC actually believe that classifying modern ISP services as pure “information services” is the most reasonable interpretation of Congress’s will (as expressed in the Act of 1996)? Or is this just a legal fiction they assert because Brand X says they can and because they believe the public policy justifications should override Congress’s will?

If they don’t really believe it, shouldn’t they stop pretending and submit to the will of the 1996 Congress by maintaining the prior regulatory regime over physical infrastructure? I get why Democrats don’t bring this up—I don’t really think most Democratic officials believe in agency subordination to Congress—but that’s why I’m not a Democrat. (Well… it’s one reason.)

If they do really believe it… how? Who gave you this idea? How did you react when reading Brand X for the first time, especially the dissent? What did you think when Justice Thomas recanted? How is it that most of the Right recognizes Brand X as misguided except telecom lobbyists and the Republican FCC commissioners they lobby?

QUESTIONS OF NATURAL MONOPOLY

Convincing everyone that, under the Telecommunications Act, modern ISPs must be regulated as Title II common carriers is only part of the discussion. As Commissioner Simington pointed out in a Q&A with the Free State Foundation, the FCC could, theoretically, place all modern ISPs under Title II, then use regulatory forbearance to suspend enforcement of all of Title II.

So we still need to ask what public policies are actually wise. I made the case in my original blog post that telecoms are natural monopolies and should be regulated accordingly. Republican commissioners have offered some counterarguments.

I have to be frank here: this section of RIFO (117-139) is the strongest, by a mile. With only one or two exceptions, it strikes me as a serious attempt to grapple directly with the facts, and I suspect it’s the part the Republican commissioners really polished and believed in. Without ever using the words, “natural monopoly,” RIFO acknowledges that this market has natural monopoly characteristics (126), then develops an evidence-based case that as few as two competitors in this market are sufficient for real competition, without automatically devolving into cartel behavior. I have just enough economics to say that this is an unorthodox position; I do not have enough economics to be confident it is wrong (except, perhaps, over the very long term).

Still, the Republican commissioners’ position does raise some questions for me:

6. When will wireless broadband become competitive enough to challenge cable incumbents on price, speed, and/or quality, for the great majority of consumers?

“How [might] tech changes since 2014, such as the emergence NGSO satellite service or the increasing prevalence of fixed and wired broadband, affect “natural monopoly” analysis?” asked Commissioner Simington in May 2021. “I think we can agree that [the monopoly issue] grows less applicable with every year. Not just new providers, but new technologies, are rapidly entering the market,” he reassured us in February.

Here are some more reassuring words on the subject: “Other ways of transmitting high-speed Internet data into homes, including terrestrial- and satellite-based wireless networks, are also emerging.” Who wrote them? (Hint: it wasn’t RIFO.)

Answer: Justice Clarence Thomas, in the Brand X decision (that he has since abjured), in 2005… 16 years ago. (He was paraphrasing the 2002 Cable Modem Order, from 19 years ago.)

I don’t point this out to drag Simington or Thomas (my favorite justice). I don’t question their earnest belief that disruptive, competitive technology is just around the corner. But it seems fair to say that it is not here yet.

Twenty years after the Cable Modem Order, the best fixed-wireless provider in my dense, wealthy Twin Cities suburb tells me that I can probably get speeds of 2-3mbps (unless it’s raining). Comcast currently sells me 150mbps, with offerings up to 1000mbps. Comcast’s sole local wired broadband competitor, CenturyLink, has similar offerings at similar prices. (HughesNet, a broadband satellite service, offers my area much lower speeds at much higher prices; I do not know any HughesNet subscribers.)

I have always liked the idea of threatening to regulate monopoly markets (rather than actually regulating them), just to stall them until a disruptive technology comes along and restores free market competition. But stalling has its limits.

Regulation-skeptical FCC commissioners have been telling us for twenty years that new broadband technology, capable of competing with wired incumbents on price and speed, is just about to arrive. When will it actually do so? And can we please wait until it does arrive before we make major decisions premised on its viability?

7. Even if fixed wireless and other emergent transmission technologies emerged full-fledged tomorrow, why would these competitors be any less prone to natural monopoly compared to cable broadband and traditional common-carriage phone lines?

Natural monopolies prevail in markets with very high fixed costs and very low (inverted) marginal costs. The paradigmatic examples are all networks (phone networks, power networks, airline networks, social media networks, etc.). You have to spend vast amounts of capital to build the network out to a competitive level, but then connecting new users is trivial, making competition ineffectual. This is not a fringe theory; natural monopoly was on the AP Economics curriculum when I was in high school. “The Persistence of Natural Monopolies” is a good, layperson-accessible, mainstream scholarly article about them (incorporating Demsetz‘s critiques).

Emerging telecom technologies are (speaking as an I.T. guy) extremely cool, and they are great news for rural customers who might not otherwise have broadband access… but they all follow this pattern. Putting a satellite into orbit (geosynchronous or not) is a huge capital investment, and selling new consumers a satellite dish to connect to it is so cheap it lowers overall costs. Building a fixed wireless base tower is a large capital investment; pointing the tower at a new customer is not.

They’re all natural monopolies. They’re all going to follow the same old pattern of consolidation and monopoly—a pattern that will hold, not only in direct competition with other emerging technologies, but when they go head-to-head with cable and geosynchronous incumbents. Fixed wireless may very well add broadband service to areas that don’t currently have it, or which only have one option… but they aren’t going to provide rural areas with six options or ten. They’re certainly not going break into dense urban markets (like mine) where there are already two established incumbents.

That’s not the companies’ fault; it’s just an economic fact.

The FCC’s unorthodox contention in RIFO is that, even with moderate-to-high concentration and limited competition, high sunk costs compel the incumbents to really fight hard for customer satisfaction. In the long run, this seems unlikely: 19th-century railroads all eventually consolidated into regional monopolies because of efficiency, and that seems likely to happen here, too. But, as Keynes famously said, “In the long run, we’re all dead.” Perhaps the Republican commissioners are right, and I am borrowing the future’s trouble by worrying about this before consolidation actually occurs.

On the other hand…

8. Have we not found these natural monopoly forces effectively irresistable, in a variety of industries, under a variety of regulatory regimes, over relatively short periods of time? Have we not moved inexorably from more choices to fewer in markets with these characteristics?

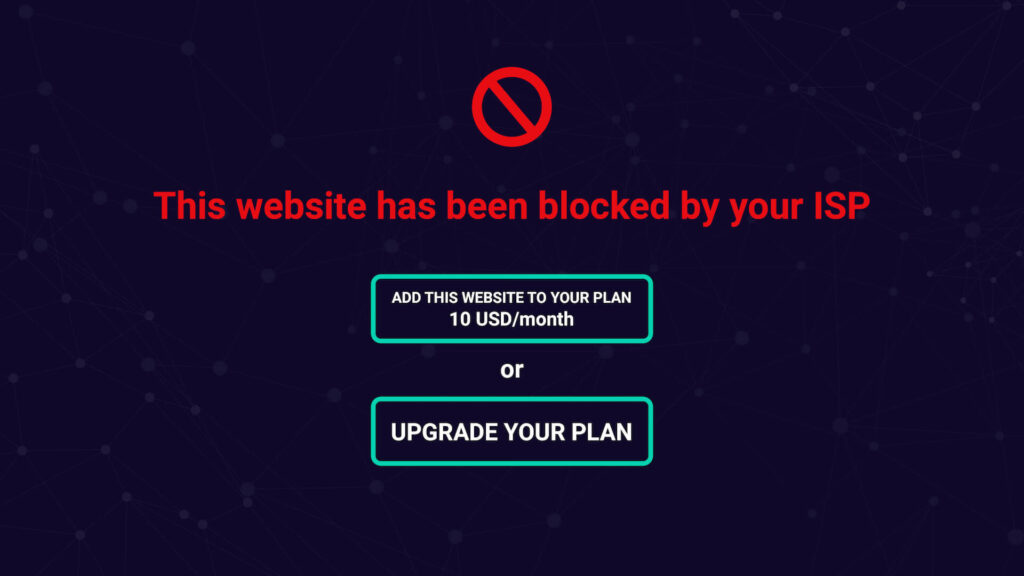

This image suffices:

It may also be relevant to ask how many ISP options your house specifically had in 1998 (when the Stevens Report came out) versus how many ISP options your house specifically has today.

Moreover, even when you had more ISP options, how many options did you have for the physical infrastructure those ISPs ran on? Which leads to my next question.

9. If the FCC is looking to bring back competition in the ISP space, why isn’t it looking at the only regime that ever worked for ISP competition—indeed, the only competitive regime I’ve seen that seems to work in natural monopoly markets, period?

The FCC might consider why traditional ISPs were (and, occasionally, still are) able to exist. Traditional ISPs leased lines and took advantage of Title II unbundling rules to “ride along” on the infrastructure of telecom incumbents. They didn’t have to build out a vast physical infrastructure to compete with the incumbents; they simply used the infrastructure that was already there, paying a fair price for their use of it (as determined by the FCC). Their non-physical ISP offerings (DNS, email, caching, etc.) would then compete directly with the wired incumbent’s ISP offerings, and with other ISP offerings from competitors like MindSpring and EarthLink. Effectively, competition was allowed for everything except the physical transmission infrastructure (due to the natural monopoly tendency of physical transmission infrastructure), and, in fact, regulators actively supported and insisted upon that competition—up until the Cable Modem Order.

This was very similar to how Texas’s “deregulated” power industry works. In Texas, incumbent power companies that build the transmission lines still own the transmission lines… but they are required to share the lines, for a fair price, with small companies that generate cheap power but don’t have transmission infrastructure of their own. So Texas accepts that there is a natural monopoly on the physical transmission infrastructure, and regulates it as a utility… but supports competition on the services like power generation, where lower fixed costs and increasing marginal costs mean that there is no natural monopoly.

Since Title II was never extended to cable broadband and modern ISPs, the FCC has effectively choked off this form of competition, although it still exists in a limited way on legacy Title II infrastructure. Even under the Title II Order, the FCC avoided imposing Title II unbundling and interconnection rules that could have allowed traditional independent ISPs to make use of cable transmission infrastructure.

Instead, the FCC has tried to create competition in the natural monopolies of physical transmission infrastructure. As the “dismal science” predicted, this has not worked. Guise Bule has written, “Today we… struggle to imagine a time when, depending on your region, you could choose from any one of potentially hundreds of ISP’s. In 2017, the consumer broandband [sic] market is an effective duopoly in some parts of the country.” (See Figure 4 here, although note the improvement here.)

To be sure, even extending Title II to broadband might not resuscitate traditional ISPs. Competition in online services (search, blogs, e-commerce, hosting) has been fruitful and prolific since day one. But competition in online access was always dicey, even under the old regime, because traditional ISPs almost by definition could not compete on price or speed (because they were all using the same incumbent infrastructure). Instead, they had to compete on pure “information services,” such as circa-1995 AOL web portals and DNS. But it turned out that (contra RIFO 48) consumers didn’t care about those very much, so consolidation was happening even before 2002.

Yet this still seems like a more promising path than exempting the most powerful telecoms in the country from telecom regulation, despite their natural monopoly, then hoping that disruptive technology will eventually show up and save the day.

QUESTIONS ABOUT RED HERRINGS

Sometimes, Republican FCC commissioners, while acknowledging some problems in the ISP market, go on to suggest solutions that, to me, raise more questions than they answer.

10. Is it plausible that transparency alone will suffice to “shame” monopolies into good behavior?

In RIFO 239-243, Republican commissioners argue that bright-line conduct rules aren’t necessary. Their transparency rule “obviates” the need for conduct rules, they say, because, “as public access to information has increased… ISPs resolv[e] openness issues themselves.” Paragraph 241 is truly astonishing and needs to be quoted in full:

History demonstrates that public attention, not heavy-handed Commission regulation, has been most effective in deterring ISP threats to openness and bringing about resolution of the rare incidents that arise. The Commission has had transparency requirements in place since 2010, and there have been very few incidents in the United States since then that plausibly raise openness concerns. It is telling that the two most-discussed incidents that purportedly demonstrate the need for conduct rules, concerning Madison River and Comcast/BitTorrent, occurred before the Commission had in place an enforceable transparency rule. And it was the disclosure, through complaints to the Commission and media reports of the conduct at issue in those incidents, that led to action against the challenged conduct.

The factual claim here about Madison River and Comcast/Sandvine is jaw-dropping. The Republican commissioners claim that those incidents were resolved by disclosure, not by enforcement. While it is true that the incidents only became matters of national debate after the nation found out about them, it was, in both cases, the threat of FCC enforcement that got them resolved.

True, Comcast-BitTorrent was settled before the FCC issued its final ruling in 2008, as RIFO states… but, as RIFO‘s own citation shows, the resolution came after months of pressure from the FCC, culminating in Republican FCC Chairman Kevin Martin directly, publicly threatening enforcement. A transparency rule would have helped bring the throttling to light earlier—but only the threat of FCC enforcement actually ended the throttling. As a regular user of BitTorrent (yes, for legal content), the Sandvine throttling incident remains a vivid memory.

The Madison River claim is the real shock here, though. Madison River absolutely did not end its anti-competitive practices because they were exposed; they knew going in that they were going to be exposed. Madison River ended those practices because Madison River was regulated as a Title II common carrier and the FCC was investigating it under Title II rules! It says so! Right there in the consent decree! 47 USC §201 is the very first section of Title II! Am I completely misreading this, or am I being gaslit?

For what it’s worth, I do think the RIFO transparency rule is an improvement on the Title II Order‘s transparency rule. But transparency alone has not protected consumers. You would not expect it to, since these are natural monopoly markets. Incumbents know they have lock-in, market power, high switching costs, and that you the consumer have few or no other options anyway. I am not a corporation-hater. I support Citizens United, and I recognize corporations’ critical role in our economy, but even I am not so naive as to think that corporations are motivated by public-spiritedness when a lot of money is on the line. Only the threat of FCC enforcement has normally worked.

Indeed, when FCC enforcement is not on the cards, things get bad. Verizon’s mafia-esque stickup of Netflix in 2014 was well-known, highly visible to the affected segment of the public, and resulted in a total victory for the Verizon monopoly’s value-extraction operation, with zero consequences. This happened even though the FCC had an active transparency rule. However, the FCC had no active enforcement rule at the time. (Even if they had, the Open Internet Order didn’t cover edge providers.) The Title II Order fixed that.

11. Is it plausible that the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice will be either willing or able to address antitrust violations by ISPs?

Leave aside the fact that antitrust litigation takes years—often decades—to meander through an area of law that is far more complex and uncertain than anything in RIFO’s parade of horribles about regulatory uncertainty. Leave aside how inefficient it is to require antitrust suits after competitive harm has been committed (harm that is often not fully or even mostly redressed, even by a winning suit) when the competitive harm could be clearly defined and barred before the fact. Forget all that.

At a purely practical level: we’re supposed to put the Internet in the hands of this FTC? This one? This very one? (And that’s just the tech stuff.)

Obviously, as the rule-of-law party, Republicans should fix the FTC. Some Democrats and some Republicans are trying to enforce antitrust laws for the first time in a while. But it’s very hard to read RIFO 141-154, all written before the Turn Against Big Tech, as being written in entirely good faith.

12. Must we spend so much time arguing about capital investment?

Maybe we do. Maybe we do. This is the one part of this article where I feel pretty hesitant.

Capital investment in the nation’s mobile broadband infrastructure is crucial. If regulatory action brought capital investment to a grinding halt, that would be very bad—and, indeed, it’s possible to imagine how that might happen. For example, if the FCC switched back to Title II common carrier regulation, then enforced all of 47 USC 214(a) (which requires common carriers to get FCC permission to put down new wires), that could make telecom operators throw up their hands and give up on infrastructure buildout.

On the other hand, it is much more difficult to understand how the “light-touch” Title II Order could have caused massive harm to capital investment. The Order simply prohibited telecom incumbents from throttling, paid prioritization, and other methods of monopoly value-extraction. (There was also the threat of further regulation, which telecoms and RIFO tried to present as a “Sword of Damocles” of regulatory uncertainty. However, since even a very permissive FCC can reverse itself and re-regulate, this particular Sword is hanging no matter what.) The link between “no throttling” and “lower return on infrastructure investment” is obscure, to say the least.

Granted, having their monopoly tools taken away may have hurt their stock prices—investors love a monopolist, because profits are artificially high and very safe!—and lower stock price = less money to invest in infrastrucutre. But the FCC spends the rest of the RIFO arguing (accurately) that ISPs weren’t using these monopoly tools very much anyway! So it seems like the Title II Order can’t have had much impact on telecoms’ capital expenditures.

And it didn’t! It’s very challenging to sort out the truth from the spin on this topic, and every side has its own squadron of lobbyists and economists putting out favorable (but contradictory) statistics. Yet, even if we accept the most pessimistic arguments about Title II’s drag on investment, we aren’t talking about an apocalypse: RIFO 91 claims that the Title II Order caused up to 5.6% investment decline between 2014 and 2016, or perhaps 3.1% by a different analysis (RIFO 90). That is to say: in 2013, telecoms spent $76 billion on capital expenses, this ticked up to $78 billion in 2014, then back down to $76 billion again by 2016.

Free Press has more optimistic estimates, but let’s assume the pessimistic estimates are correct.

Is this slowdown good? No.

Is it the Title II Order‘s fault? It’s hard to see how, since parallel rules had been in place most of the time since the 2007 BitTorrent-Sandvine controversy. If net neutrality rules damaged investment, you would expect to see investment dip in 2008, or perhaps in 2011 after the original Open Internet Order. Even in the model cited in RIFO 90, you don’t see that. (RIFO tries to address this in paragraphs 94 & 95.)

But even if the 2015-16 slowdown were the Title II Order‘s fault (and maybe it is; I am shaky in this area), is this minor shiver in broadband spending worth sacrificing a core architectural principle of the Internet? It doesn’t seem like it to me.

And, to repeat an earlier point: the fact that we are even talking about how net neutrality regulation affects physical infrastructure investment illustrates that we are dealing with the providers of a telecommunications service, not (merely) an information service, and Congress requires us to regulate telecommunications services as common carriers.

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE GATEKEEPER PROBLEM

Finally, in light of some recent discussions at the FCC, I think it’s worth exploring what the Title II Order dubbed the “gatekeeping” issue. It’s a great conversation, but I do have some questions about how Republicans are approaching it:

13. Can the “gatekeeper” problem be viewed as a separate issue from the “monopoly” problem?

Commissioner Simington breaks down the (alleged) public policy problems Title II is intended to address in a novel way that I like a lot:

The monopoly argument is that many Americans don’t have meaningful choices among broadband providers. Thus, in the absence of a regulatory regime preventing it, monopolist providers will take advantage of their market power to favor themselves. This needn’t mean price-gouging as such; it might mean cutting deals with content providers for preferential treatment or exclusion of their competitors.

The gatekeeper argument is less about physical media. It says that an “internet intermediary” shouldn’t be able to leverage its position to block, throttle or favor content, regardless of whether a local transmission monopoly exists for any given customer, because companies who reach consumer via ISPs must have access to all consumers all the time (and vice versa.)

..the “minimum standards” argument is the argument that commercial ISPs need to face rigorous standards, with defined legal accountability, for resiliency and reliability. These standards are said to be justified because of consumers’ reliance on ISPs – we wouldn’t accept poor reliability or resiliency from utility companies, so we shouldn’t accept them here either.

This is an insightful perspective. When we talk about Title II, we sometimes treat the whole thing as one problem with one solution, but that isn’t the case: different people are concerned about different problems to different degrees, and each of the three problems Commissioner Simington lists here could, in theory, admit of a variety of solutions.

However, it seems to me that these are not actually three entirely separate problems. They are three facets of the same problem: the monopoly problem.

In a highly competitive free market, the “minimum standards” problem solves itself. There are like nine different brands of pasta on the shelves at my store, all of them essentially identical in taste, cost, and quality. I mostly buy Barilla and Creamette brands, although I’m flexible if there’s a sale. If I started finding worms in boxes of Barilla, I would stop buying Barilla. I have many comparable options, my switching costs are low (I don’t have to spend two days on tech support to cancel Barilla and two more days to sign up with a new pasta provider), and I have no customer lock-in (no rented equipment, no early cancellation fee, no “triple play” home pasta package).

In a highly competitive free market, the “gatekeeper” problem also mostly solves itself. If Creamette one day decided that “rigatoni is white supremacy” and stopped selling that specific pasta shape to consumers, I would just buy Barilla’s rigatoni.

The only risk here, in this highly competitive market, is that gatekeeping can be contagious. On social media networks, the decision to ban Donald Trump from one platform quickly spread to other platforms, and platforms that weren’t sufficiently anti-Trump, like Parler, were attacked at the infrastructure level. The same could happen in Woke Pasta, with Barilla’s rigatoni getting pulled soon after Creamette. But, even there, it’s not THAT hard to start a pasta company and sell great rigatoni, and some intrepid capitalist is going to do so—at least, as long as the grocery store itself doesn’t get woke.

This is why highly competitive free markets are the most powerful engines of prosperity and consumer welfare in the history of the world. The great insight of Reaganomics was that any product that can be sold in a highly competitive free market should be.

The great error of Clinton-Bushonomics was forgetting that some products can’t be sold in a highly competitive free market. For the reasons I’ve laid out both above and back in my original 2014 blog post, transmission capacity over a physical telecommunications network is one of those products.

Because consumers have few or no substitute options, with high switching costs and substantial lock-in from sellers, the market for broadband is naturally monopolistic. It will always act like a utility market because it is a utility market. Gatekeeping and minimal standards issues therefore will not solve themselves.

One frustrating part of the 2014 Netflix stickup was that we already had the solution, and simply refused to use it. Congress passed 47 USC 251 in 1934, because our Republic already identified this exact problem with phone carriers a century ago, recognized that the problem could not solve itself, and imposed a reasonably balanced government rule to take the place of raw monopoly power. Even under the Title II Order, the FCC’s Democrats were unwilling to embrace these democratically-passed laws governing interconnection agreements, which have worked in the telecom market for 90 years. They preferred instead to adopt vague and arbitrary rules that gave FCC Democrats the maximum amount of power (and telecom execs maximum uncertainty).

Commissioner Simington raises a concern that the cost of solving these problems may outweigh the benefits. He’s right to be afraid! The government is far less efficient than a highly competitive free market, and government has been known to do incredibly stupid things like impose price controls as a substitute for welfare payments. I’m glad we have Republican FCC commissioners who understand that, and can help shape a regulatory regime that imposes the necessary rules—and nothing more—in the most efficient way possible. But I see RIFO as an abandonment of that task, not its fulfillment.

14. Why would bad, “gatekeeper” behavior by other online actors discourage us from regulating bad “gatekeeper” behavior by ISPs?

It is very obvious that “gatekeeper” issues online go well beyond ISPs. Internet edge providers (app marketplaces, social media networks, video-sharing sites, etc.), many of them far less regulated than ISPs have ever been, are increasingly censorious. Some of those providers, like Facebook, are structured as unregulated monopolies (whether FB is a “natural” monopoly or not is a matter of some debate). This behavior is self-evidently destructive to American public life… and, worse yet, it appears to be asymmetrically targeted at conservatives, which is even more dangerous.

This is exactly what net neutrality advocates have always feared from modern ISPs, if ISPs were ever allowed to exit net neutrality regulation for any length of time.

Obviously, bad edge providers need to be addressed by some mechanism, perhaps starting with social media. Sen. Hawley offers the most conventional free-marketeer response; Cory Doctorow has some further ideas (shorter here); Curtis Yarvin has some other ones. (Yarvin is wrong, but essential reading nonetheless.) Despite some early noises, it is unclear whether or how the FCC will be able to help fix social media.

But, bafflingly, both Chairman Pai (RIFO 265) and Commissioner Simington (page 3 here) have taken this bad “gatekeeping” behavior by other edge providers as evidence that we don’t need to be concerned about bad “gatekeeping” behavior by ISPs, and that Title II regulation of ISPs is unnecessary. In a world where mild social media pressure leads a giant conglomerate like Amazon to wipe out a conservative-coded social media site (Parler) and stop selling perfectly cogent, charitable, conservative-coded books (When Harry Became Sally); and it faces absolutely zero consequences before, during, or after; and it appears committed to doing it again… why would we assume that Comcast’s backbone will be any stiffer when the mob comes to have First Things kicked off the Internet for being transphobic? The only thing stopping them is the looming threat of Title II.

In 2017, the CEO of CloudFlare, a key edge provider of online infrastructure, “woke up [one] morning in a bad mood” and decided to kick the Daily Stormer off the Internet. Obviously, the Daily Stormer is vile, but CloudFlare’s action was, by the CEOs own admission, “arbitrary” and “dangerous.” He practically begged someone to take this power away from him. Instead, RIFO uses it as a reason to give that same arbitrary power to the people who own the physical Internet, who are already even more powerful than CloudFlare.

We must recognize that these incidents show us what the ISP world would look like if ISPs hadn’t spent almost all of the past thirty years under regulation (or imminent danger of it). Parler-AWS makes a good case for keeping and deepening Title II rules on ISPs, not abolishing them. FCC authority over Amazon’s web-hosting service is not yet clear to me, but its authority to impose Title II on ISPs couldn’t be clearer—and, it seems to me, should be exercised immediately, so we can move on to those other bad actors.

15. Without the intervention of Congress, what alternative options are available for preventing gatekeeping in the modern ISP market?

The “gatekeeping” problem has been addressed before. Congress’s solution to it was common carriage rules. Congress told railroads, straight-up, that they can’t gatekeep; they have to carry all legal passengers and all legal freight to all available destinations. They later extended this logic to phone calls. Perhaps, in the future, they will extend it to cloud web hosts.

We know the FCC has the authority to regulate gatekeeping in the ISP world using the common-carriage rules Congress gave it, both because the law plainly says so and the courts agree that’s what the law means.

Is the Republican answer that this truly isn’t a problem, because companies are too focused on the bottom line to enforce ideology anyway? Even profitable ideology? (The sparse record of past net neutrality violations does truly seem to be their strongest argument.) But is that position sustainable, after the Great Awokening?

Is the Republican answer that this is a problem, but it is fully addressed by the FTC? Is that sustainable, given not only the byzantine, post hoc nature of antitrust enforcement, but also the post-Microsoft ineffectiveness of the FTC, and recent revelations about FTC’s rank abandonment of its post in the Facebook case? Should that be our answer, when Congress has clearly given the FCC (not the FTC) the responsibility to regulate common carriage rules in communication networks?

Is the Republican answer that this is a problem, but sunlight is the best disinfectant, and transparency will solve everything? Is that sustainable, given the virtually complete absence of evidence for it over the past two decades of telecom regulation (not to mention the past century of utility regulation)?

Is the Republican answer that this is a problem, but the costs of common carriage regulation are too high to fix it? So we just have to accept that, sometimes, conservative websites (not to mention small businesses whose offerings threaten ISP conglomerates) may be kicked off the Internet, or at least to its curb? And what are those costs again, exactly? Possibly, arguably, a modest slowing of how quickly we build out new broadband infrastructure? Is this a trade-off Republican voters will accept? Should it be?

As @PoliticalMath likes to put it: “I’m open to ‘your solution is bad; here’s a better one.’ I’m not open to ‘your solution is bad, there is no solution.'” FCC Democrats have offered a solution: Title II regulation. It’s not a great solution, and they didn’t implement it all that well, but it seems to me to be the best on offer. If Republican commissioners have a better one, I would love to hear about it—but I’ve been watching them for a lot of years. Their answer to date has been to say that no action is necessary, because the problems we had the last time net neutrality was weakened were rare and unlikely to recur. I wish I shared their optimism.