NOTE: This post was originally published at my Substack. The footnote links go there instead of to the bottom of the page.

In last week’s article, What Are Your Covid Odds?, I calculated your odds of surviving covid based on your age.

In the comments, someone asked, “How are these odds affected by conditions such as obesity?” This is a question I hear routinely, often as the first premise in an argument that young people don’t really have to concern themselves about covid as long as they have no comorbidities. This is not an unreasonable argument at first impression, so let’s explore it.

For comorbidities that affect only a relatively small slice of the population, there’s a pretty easy way of doing this—a shortcut. First, you look up something called the odds ratio for covid mortality with your condition. “Odds ratio for covid mortality” is a fancy scientific way of saying “this is how much more likely you are to die of covid if you have this condition.” Once you have your odds ratio, you just take the official De Civ odds of dying for your age group (see last week’s post!) and multiply them by the odds ratio.

For example, say you’re 30 years old and pregnant. There aren’t very many pregnant people at any given moment, even within that age group, so it’s safe to take the shortcut. According to one study1, the odds ratio for covid mortality while pregnant is ~1.84. So if you get covid while you’re pregnant, all else being equal, you’re 1.84 times more likely to die of covid than if you weren’t pregnant. According to our chart, your odds of dying of covid at your age in general are 1 in 1,771. Pregnancy increases your odds of death to 1 in 963.

But obesity is far more common, and thus (along with age) one of the most significant drivers of the total death toll in the American covid epidemic. An odds ratio for obesity is not that hard to come by: 1.36. The problem here is that a whole lot of Americans, in every age group, are obese. So many, in fact, that the obese people (and their deaths) make up a pretty substantial part of the death rate overall. In order to make judgments about the overall odds for obese people, we can’t take the shortcut and multiply the overall odds by 1.36. Instead, we have to explicitly calculate the odds for non-obese people, then multiply that by 1.36. How?

Boring Caveats

Well, first, we have to find out how many obese people there are in each age group. The CDC website was able to help me out with that a little bit, but their age groups for obesity did not match their age groups for covid, so I ended up having to fudge the obesity rates for each age group a bit.

Then, we have to find out how many obese people got infected with covid. For the purposes of this calculation, I assumed that obese people catch covid at the same rate as non-obese people. This is probably not quite true, but it is basically impossible to be sure how much more likely obese people are to catch the ‘rona in the first place. You’d have to disentangle their higher positive test rate from the facts that obese people get more severe cases; that we are less likely to test people who have less severe cases; and that, even when we do test people with few or no symptoms, they are more likely to have a false negative test result. So I’m satisfied enough with my assumption for tonight, even though it, too, as a bit of a fudge.

Once we have per-age-group obesity rates and obese vs. non-obese estimated case counts, it’s just algebra.

I’ll spare you the details. They are in my Google Sheet. Here’s my scratch paper, which I certainly did NOT clean up for you to read:

Many stupid errors later, I finally got results that both looked correct and checked out against the 1.36 odds ratio I’d started with. Hopefully they’re also right? Feel free to Reinhart & Rogoff me in the comments if not.

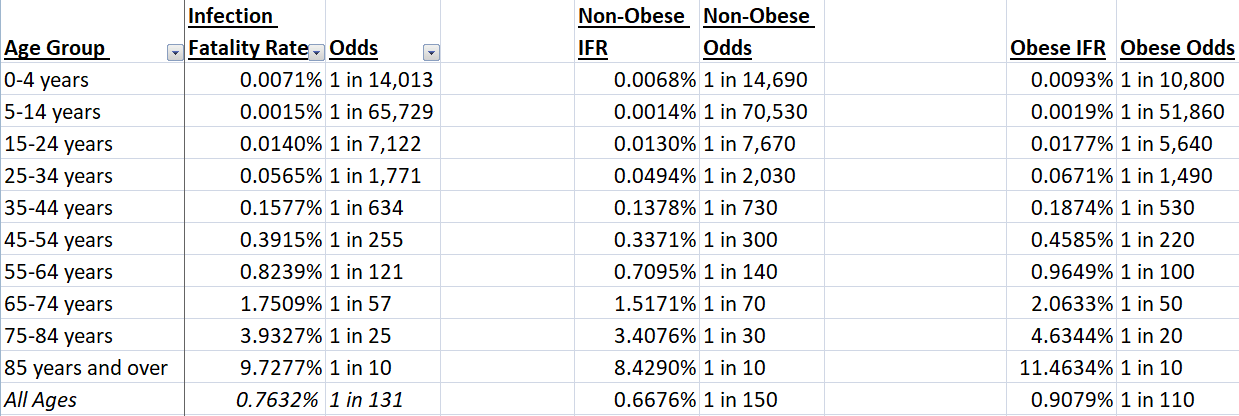

Because of the fudging I described above, I rounded these obese/non-obese odds to the nearest 10. (The overall odds are still precise, so no rounding there.)

Results & Discussion

All in all? Being not-obese provides some protection against covid. But not a ton.

I’m 32. The overall odds for my age group are 1 in 1,771. Last week, I wrote about how I would take prudent2 precautions against a 1-in-1,771 chance of dying, and I explained that I thought most people would do the same thing for most similarly unlikely causes of death, like house fires or choking.3 Only when my odds start to slide below about 1 in 10,000 do I start to feel like there’s no real point.

I’m not obese, so my actual odds of death, taking that into account, are more like 1 in 2,030. I’m pleased by anything that lowers my odds of death. But, guess what? I would still take precautions against a 1-in-2000 chance of death! That’s still right in the sweet spot between house fires and choking!

Before we leave, I want to make note of something another commenter noted last week: covid can do a lot to you besides kill you. It can leave you with other serious injuries like myocarditis or reduced lung function. It’s not clear to me that Long Covid is more prevalent than, say, Long Lyme, but it certainly does appear to be A Thing of some kind. Furthermore, simply being hospitalized right now creates problems for others, because hospitals are stretched well beyond their capacity right now, and that lack of capacity is literally killing people who need hospital care and can’t get it—including people I know. I’m writing a big messy post about this stuff, but it’s slow going, and I keep getting sidetracked by stats.

Meanwhile, in these more statistical posts, I focus on death rates, because death rates are a very easy, measurable statistic, and because death rates are how we compare between different diseases and various other health threats, like car accidents and war. (Flu can leave you with compromised lungs, too, but we never talk about that, either!) I can give you odds of you dying of covid. I can’t give you odds of you catching covid and experiencing profound suffering. Trust me, I would if I could!

The problem (the problem the big messy post is all about) is that there aren’t very many things you can do to reduce those odds.

Never stake your life on one study, outliers happen, science is in a replication crisis anyway… but one good study is not a bad starting point.

Somewhat effective, low-cost, low-effort.

A commenter cast some doubt on the data source I used to get the lifetime odds for dying of a house fire or choking. Looking at his objections, I think he’s right to be suspicious: how can you have lifetime odds of dying of lung cancer at only 1 in 6 when 1 in 4 of annual American deaths are caused by heart disease?

But if you go with easier-to-grok annual rates of death, it only strengthens my argument: your odds of dying in a fire annually are only 1 in 93,408, an order of magnitude lower than my data source. And yet you still have a smoke detector! So I suggest you get a vaccine for this thing that is many times more likely to end your life, if you haven’t already. It won’t guarantee you live, but it will help.