Or: 13,000 words about sex and gender. Yes, you can run that through Google Translate.

NOTE: This post was originally published at my Substack. The footnote links go there instead of to the bottom of the page.

Introduction

This article is about gender identity and transgender people. After months of work, I finished the first draft on November 4th… 2015. I was in the middle of proofreading, about to post it, when I noticed an error. The error was completely fatal. My whole position on sex, gender, and transgender identity was based on it. I was totally wrong. I had to revise all my beliefs and start from scratch.

For years now, I have kept writing and rewriting this article. Each rewrite has been wrong in a new way. Then I have to go back to the bookshelf, read some more, listen some more, and try again. I keep trying because I feel I owe it to certain people in my life to do my very best to understand gender, and I don’t seem able to understand it better without writing about it… over and over again. At various points in this process, I have held just about every single belief about sex, gender, and transgender identities that it is possible to have, from far-right views to far-left ones. Each seemed strong when I started writing it up, and stupid by the time I finished. You are reading this version because, for the first time in five six seven years, I finished a draft and still found it reasonable.

Many people’s thinking about gender identity is limited by ignorance and knee-jerk prejudgment, often informed by religious dogma. I know because mine was, and perhaps still is. (I need not elaborate; “religious dogma causes bigotry” is such a pervasive idea in American literature, memoir, and coffee-shop chit-chat that every living American knows what I’m talking about.)

Many other people’s thinking about gender identity is constrained by peer pressure and fear—fear of financial consequences, social consequences, legal consequences, for saying the wrong thing or thinking the wrong thought—often informed by intersectional dogma. I know because mine was, and perhaps still is. (I recommend The New Thoughtcrime, a series of modest essays by someone who was very deeply engaged in online Discourse about gender, to anyone who has participated in that capital-D Discourse.)

I share this latest version in hopes that it will help others who are thinking through these same questions, and who are struggling with similar dogmas. I do have (a few) answers. I can’t promise they are right, but I think I can at least promise that I really tried. If nothing else, I hope that my thinking is careful enough to give you a jumping-off point for your own thinking. I will take it slowly and carefully. Now more than ever, it is better for me to be clear than to be concise.

However, if you don’t want to read this, please don’t. In the process of getting to the end, I will try to fairly consider ideas that some of my friends consider to be (at best) indulgence of mental illness and (at worst) an attack on civilization itself. I will also try to fairly consider ideas that some of my (other) friends consider direct attacks on their identity, ideas that they find unutterably hurtful. I do not wish to upset those friends, or you. If this sounds like an article where reading it would crush your spirit, or make your ears steam… don’t. It probably will, and how does that help you or me or anyone? Please know simply that I do not reject anyone’s personhood, that I deny no one’s existence, that no disagreement about a point of ontology and language (no matter how important) can possibly change how much I care about my friends… and then just close the tab.

For those that remain?

…Let’s start with a word about words. This will seem like a silly (and lengthy) digression, but bear with me.

Words are Funny Things

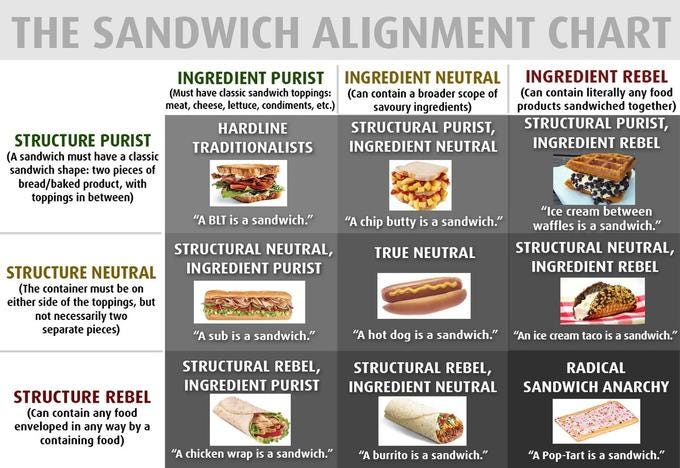

Words have meanings, but those meanings are often vague. Everyone agrees that a PB&J is a sandwich. Most people agree that a hamburger is a sandwich. But is a wrap a sandwich? How about a hot dog? Opinions conflict:

Vagueness of this type exists for many words. Take “table.” What, exactly, counts as a table? Does it have to have four legs? Any legs? Is a big flat rock a table? How about a small, curvy rock that wouldn’t really make a good table? What if you try to use it as a table anyway? Does the act of using a rock as a table make the rock a table? Is the ground a table? Yes, there are lots of things out there that, by common consent, are unambiguously tables. IKEA sells a lot of Unambiguous Tables. But there are also a lot of things that fall into a Table Gray Area. Whether we count those things as tables is simply a matter of convention, or even personal taste.

This is bad enough, but words aren’t merely vague. Their meanings can actually change, in many different ways, for many different reasons.

“Awful” used to mean “awe-inspiring.” The aurora borealis or an incredible work of art or the climax of a Bach’s Mass in B Minor might be praised as being “awful.” However, over time, “awful” was used in negative contexts so often that the word came to mean “very bad.” It is no longer accurate to call the aurora borealis awful. The aurora hasn’t changed. Our reaction hasn’t changed. But the word has changed.

The word “gay” used to be a synonym for “happy.” It eventually developed a secondary meaning which was synonymous with “rakish,” and, from there, the word further evolved to mean “sexually immoral.” It seems that it was then applied as a euphemism for homosexuals, since homosexuality was considered the apex of sexual immorality at the time. The euphemism eventually became so common that it overtook the original, non-euphemistic meaning. Now “gay” is a synonym for “homosexual.”

Sometimes, people even invent new words out of thin air. William Gibson invented the word “cyberspace” and put it in his 1984 cult-hit novel Neuromancer. It was just a nonsense string of letters, until, quite suddenly, it was a word. By 1990, it was ubiquitous among computer nerds. By 1994, the mainstream had got its hands on it. In 1996, Congress held hearings on it. And, in 1997, the Oxford English Dictionary formally recognized “cyberspace” as part of the English language.

Sometimes, people dig up old words and assign completely new meanings to them, meanings that are barely connected to the original word. For instance, since 1350, the word “mouse” has described this:

However, in 1965, an engineer named Bill English decided that this is also a “mouse”:

You can kinda see it, with the cord at the end being kinda like the mouse’s tail. There’s an analogous relationship between the animal and the computer accessory. But, thanks to Bill English, this is now a “mouse,” too:

With that mouse, you can no longer see any connection to a small furry creature. The two meanings of the word “mouse” have completely diverged.

Moreover, words only have meanings within larger systems called languages. To someone interpreting words according to the English language, “mana” is a kind of supernatural energy, or a key resource in the game Magic: The Gathering. In the Latin language, however, “mana” – the exact same set of four letters – is an action meaning “pour out.” If you interpreted the word “mana” according to the Quenya language, a language which J.R.R. Tolkien made up entirely by himself, it has the same meaning as the word “which” has in English. There’s nothing special about these letters that links them to a meaning. In the Japanese system, you can’t even write the word “mana,” because Japanese doesn’t use the same alphabet, or even quite the same concept of “words.”

We humans have found or created meanings in ourselves and the world around us, then we tied those meanings down to some completely arbitrary markings that we came up with. The meaning of each particular marking changes from community to community and from year to year, in thousands of different ways.

My long-winded point here is just this: words are tricky things. Try and pin down their meanings, and, sooner or later, they tend to slither away and mean something else. Even when their meanings seem relatively fixed, words can be vague and may contain a multitude of meanings. Their meanings are determined not by some verbal science, but by sheer, fickle, social convention.

On the other hand, although words are completely made up, the meanings beneath the words are often real. Take a look at this:

I don’t know what you call that stuff. Maybe it’s “water” to you. Maybe it’s “vatten” (Swedish), “aqua” (Latin), 水 (Japanese), “unga” (the extinct Sacata language), or “blQ” (Klingon). Maybe you’re an alien who has never seen it before, and you have no word for it. Or maybe you live under a totalitarian regime which, for political reasons, makes you refer to this stuff as “milk,” or not talk about it at all.

But the stuff is real regardless. The stuff in that picture will get solid at 0 degrees Celsius and turn to gas at 100 degrees C. If you grab one molecule of it at random, it is likely (though not certain) that it will turn out to have two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom. If it floods your village, it will wreck your house and quite possibly kill you—even if the government tells you it doesn’t exist and you shouldn’t think about it. The existence of water is an objective fact, even though the name we give it is a matter of convention.

A contested sentence

Here’s a sentence for you: “Transwomen are women.”

Is this sentence true?

We can very easily make it true. I have just invented a new language, “Jamesian.” The Jamesian language is identical to English in every way except for two things: in Jamesian, the word “w-o-m-e-n” is a synonym for “celestial bodies,” and the word “t-r-a-n-s-w-o-m-e-n” is a synonym for “comets.”

So, in Jamesian, the sentence “transwomen are women” is equivalent to “comets are celestial bodies.” I trust we will all agree that comets are celestial bodies. Therefore, in Jamesian, the sentence “transwomen are women” is true. But it isn’t a sentence about Chelsea Manning and Caitlyn Jenner; it’s a sentence about Haley’s and Hale-Bopp. It’s true, but not in a way that is at all connected to what most people mean by it.

If we want to find out whether the sentence “transwomen are women” is true in the English language (instead of in Jamesian), then we need to find out what those words “transwomen” and “women” mean in English. As we saw in our brief look at words above, that… might get tricky.

What is a woman?

When asked, “What is a woman?” many modern people will say something like, “A woman is a human being with two X chromosomes.” This is silly, and we should put a stop to it right now.

The English language has had the word “woman” for over a thousand years. Every other human language that has ever existed has one or more synonyms for “woman.”

Some three thousand years ago, the Book of Genesis was compiled, and it said, “זֹאת הַפַּעַם עֶצֶם מֵעֲצָמַי, וּבָשָׂר מִבְּשָׂרִי; לְזֹאת יִקָּרֵא אִשָּׁה,” which (according to translators) (no, I do not know Hebrew) means almost precisely the same thing as the English sentence, “This, now, is flesh of my flesh, and bone of my bones; she shall be called Woman.”

Nearly four thousand years ago, in the Code of Hammurabi, written in cuneiform so ancient I can’t even copy-paste it because Unicode doesn’t support it, the law stated: “If a man take a woman to wife, but have no intercourse with her, this woman is no wife to him… If a man wish to separate from a woman who has borne him children, or from his wife who has borne him children: then he shall give that wife her dowry, and a part of the usufruct of field, garden, and property, so that she can rear her children.”

We discovered sex chromosomes in 1905. If a woman were defined by her sex chromosomes, then we couldn’t have understood the word “woman” before 1905. But we’ve had a remarkably consistent understanding of the word “woman” for thousands of years. So, while certain sex chromosomes may be closely correlated with people we understand to be “women,” women cannot be defined by their sex chromosomes. Something else is at work here, a distinction even Hammurabi and Juvenal and Shakespeare could understand with their primitive science. What was it?

Well, why don’t we go look? The first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary began its long publication process decades before sex chromosomes were discovered, so let’s see what the London Philological Society thought! After all, one of the reasons the Oxford English Dictionary is so good is because it is so comprehensive, reaching back as far as a word’s history can go. It will tell us both the contemporary and past understandings of “woman.”

The OED first defined “woman” in 1928 as “an adult female human being.” According to the OED citations, this meaning of “woman” dates back to at least 893 AD. And it’s an okay definition… but it seems to dodge the core question we’re trying to answer. What, exactly, is a “female”?

The OED first defined “female” in 1901 as “belonging to the sex that bears offspring.” Citations for that understanding of the word go back to 1328 AD.

So, at least according to the London Philological Society of 1901-1928, the meaning of the English word “woman” is “an adult human being belonging to the sex that bears offspring.”

That fits in nicely with the definition given by Webster’s Dictionary of 1880. In Webster’s, a “woman” is “the female of the human race, grown to adult years,” and “female” means “belonging to the sex which conceives and gives birth to young.” So, in both cases, the essential characteristics of a “woman” are adulthood and the capacity to give birth.

Should we trust these two dictionaries to properly reflect the popular understanding of their day? After all, dictionaries back then could be notoriously prescriptive rather than descriptive. Maybe the dictionaries were trying to force their view of the word “woman” on a population with a broader understanding of femaleness?

It’s a fair question, but general usage seems to have agreed that a “woman” is, essentially, somebody who can give birth. In the Supreme Court decision Bradwell v. Illinois (1873), Justice Bradley and two co-signers wrote an infamous concurrence which stated, “The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfil the noble and benign offices of wife and mother.” (They then used this as a shabby excuse to deny women the right to practice law. We will return to this.)

More positively, Sojourner Truth implied in her “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech (1851) that the essential difference between men and women is their childbearing potential:

“I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?… Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.”

The idea that a “woman” is somebody who can have babies also seems to fit with our more ancient documents. In Genesis, shortly before Adam names Eve “woman,” God commands the man and the woman to “be fruitful and multiply” and, right after, to become “one flesh” as part of that mission. Clearly, the God of the Book of Genesis thinks that the ability to make babies from sexual intercourse was central to the meaning of both man-ness and woman-ness. The Code of Hammurabi features several laws (including the one I cited above) that only make sense if the word “woman” meant “someone who can have sexual intercourse with men and bear children therefrom.”

And so it seems that, for most of human history until at least the early 20th century, the words “woman,” “female,” and their synonyms in various languages were used to describe people who could gestate and give birth to babies. “Woman” was a biological category, not a social construction, although many social implications arose out of the biology. Indeed, as we saw in Bradwell, those social implications were often greatly exaggerated, then used to oppress women, plus anyone else who didn’t conform to social expectations of their sex. Nonetheless, the definition of “woman” was essentially biological.

Let us call this definition “the ancient definition of woman,” or “womanA” for short.

Addressing some difficulties with the ancient definition

There are many women who are not capable of giving birth to children right this instant. Women who are not currently pregnant have the potential to conceive and bear children, but aren’t actively exercising that potential. Some never do! Young girls are still in the process of developing the capacity to bear offspring, and can’t exercise it at all until they do. Old women generally had the capacity to bear offspring at some point, but no longer do, because the parts have stopped working. Others may have had their childbearing capacity compromised (even destroyed) by disease or accident or birth defect or medical intervention, all of which can damage the adult female reproductive system.

They are all still women, of course. It’s human nature to have two arms and two legs, but we don’t say that somebody who’s lost an arm is less human! The human nature is still there, and still yearns for its missing limb; the body has simply been maimed. Some serious injuries can be cured. Often, because of the current limits of medical science, they cannot. But we still recognize that the body of someone who has lost an arm is the body of a human whose limbs have been damaged; amputees are not another species. Likewise, a woman who has lost a uterus is still a woman—just a woman with a reproductive system that is currently falling short of its innate potential.

There are also some people, called intersex people, for whom the body has developed in such an unusual pattern that it is not even clear what sex it was trying to fulfill—if any. Whenever transgender issues are explored, intersex people tend to be pulled into the discussion and tossed around like a football in order to make some point or other. (If I got a dollar every time someone mentioned Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome in order to unsettle the ordinary classification of “biological female,” I’d buy dijon ketchup.) Some intersex people are justifiably angry about being used this way; others primly petulant.

However, in our case, we can set the question aside. The status of intersex people is not very relevant to our discussion of what “woman” means. It is possible that some people who are intersex fit the definition of “woman,” and that others fit the definition of “man.” Some may constitute a third sex, or multiple other sexes, while still others never really figure out where they “fit,” or determine that they do not fit anywhere. But we cannot answer whether an intersex person is a woman until after we know what “woman” means. The conditions of intersexed people (and those conditions are incredibly complex and varied) therefore cannot shed light on the meaning of “woman” in the first place.

A novel definition

Words can change meaning over time. Perhaps the word “woman” has changed since the early 1900s. Even if it hasn’t, perhaps it should change.

The word “gender” once referred, almost exclusively, to certain grammatical structures. However, in 1954, sexologist John Money repurposed the word (much as Bill English repurposed the mouse), and began talking about “gender” as the social dimension to the biological categories of sex. In his eyes, the ancient distinction between who could bear children (woman) and who could beget them (man) was less important, and actually less real, than the distinction between performing the social roles generally expected of women (femininity) and performing the social roles generally assigned to men (masculinity). Sex was about biology; gender was about social roles. Money’s research was later exposed as grossly erroneous and his practices more than a little creepy, but he had developed both a popular and an academic following, so his ideas stuck around (despite the David Reimer tragedy).

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Money’s “sex/gender distinction” flowered in academia, although the line between them was pretty muddy and moved around quite a bit. During those years, parts of the feminist movement advanced arguments that gender (the social performance of femininity), was the real heart of what it meant to be a woman, not biological sex. Indeed, second-wave feminists routinely argued that the social and cultural distinctions of gender and the biological distinctions of sex had absolutely nothing to do with each other. They thought the reason biological women tended, on average, to “perform femininity” better and more often than the average biological man was not because of biology (either directly or even indirectly), but because of a system of oppression, known as patriarchy, that victimized certain people, who became known as “women” as a result of their victimization.

By the year 2015, drawing on these theories, academia had settled on an alternative version of what “woman” means. While there is some disagreement on particulars, I think the broad view of academia is nicely captured by Nottingham philosophy professor and feminist activist Katharine Jenkins: a woman is a human who has “a female gender identity.”

This raises a further question: what is a female gender identity? In Jenkins’ telling, you have a female gender identity if you have an “inner map” which serves to “guide someone classed as a woman through the social and material realities of someone who is so classed.” Again: what does it mean to be “classed as a woman”? You have been classed as a woman, in Jenkins’ telling, if you have been “targeted for subordination on the basis of actual or imagined… evidence of a female’s role in biological reproduction.”

So a “woman” is someone who has, not a female sex, but a female gender identity—an “inner map” which is defined by oppression based on people thinking you can become pregnant (even if you can’t). We can call this definition “the novel definition” or, for short, “womanB.”

(There are more versions of womanB, which we might call womanB1, womanB2, and so forth; Jenkins herself explores several in a later paper. One version of womanB I encountered, which I found very intriguing, is the definition of a woman as “someone with a female soul.” However, all these definitions are built around similar definitions of gender identity, which makes them similar enough for the purposes of this essay. In my humble opinion, Jenkins’ is the strongest of these definitions, so, in the interest of steelmanning, we’ll use her womanB as “the novel definition.”)

It is worth noting that transgender activists are not the only people who believe some version of the novel definition. Many gender-critical feminists, pejoratively known in the transgender community as “TERFs,” also define womanhood as “having accrued certain experiences, endured certain indignities and relished certain courtesies in a culture that reacted to you as [a woman],” such as “suffer[ing] through business meetings with men talking to their breasts or… [having] the onset of their periods in the middle of a crowded subway.” Gender-critical feminists (who are often inspired by second-wave feminist thought) often agree with transgender activists that the “biological essentialism” of the Ancient Definition is irrational and must be rejected in favor of womanB. “TERFs” simply deny that transwomen are capable of having the “certain experiences” which, they believe, define womanhood. Many “TERFs” are (or were) academics who participated in the academic campaign to sever (performed) gender from (biological) sex and adopt the novel definition. As a result, most academic feminist discussion of “The Woman Question,” (to the extent that it is suffered to exist), is between these two camps of WomanB, rather than between WomanA and WomanB.

Everyone in academia recognizes that the novel definition is not what most English-speakers mean by “woman” in regular speech today. The dictionaries all still list the ancient definition first. But academics have decided that this is what the word “woman” should mean, and they have launched a determined effort to change the meaning of the word in society as a whole.

Academics have succeeded in projects like this in the recent past: from the dawn of the English language until less than ten years ago, the canonical definition of “marriage” was, “the state of being joined as husband and wife according to law or custom,” and this reflected common usage. Sen. Barack Obama was elected President while publicly endorsing this definition of marriage. In just one decade, both common usage and the dictionaries have changed, because the culture broadly decided that the old definition and its baggage were too exclusive. Perhaps the culture will listen to academics on this, too, and change the definition of “woman.” Perhaps we should!

But before we consider that, let’s return to our contested sentence, “transwomen are women.” We now have two competing definitions of “women.” Now let’s ask, what are “transwomen”?

Transwomen are…

Some people experience an interior sensation that their unambiguous physical sex is incorrect. That is, some people with fully-functional penises and testes, even some who have actually fathered children, nevertheless have a powerful feeling that, in the deepest and truest sense, they are not men. Their bodies reflect the full flower of manhood, but their brain, their psyche, perhaps their very soul says that their bodies are wrong, that their physical sex is (something like) a birth defect. Often (but not always), such people describe themselves as “trapped in” or “born into” the “wrong” body. They sometimes speak of their physical sex as “assigned sex,” as though their physical sex was imposed upon them by their parents and delivery-room doctors, rather than accurately observed.

(To be sure, there are some intersex persons whose ambiguous physical sex is not accurately observed at birth, and it is indisputably fair of them to describe their birth certificate sex as “assigned.” However, virtually all self-identified transwomen were born with perfectly healthy, correctly observed male reproductive capabilities. I am happy to agree that some or all of the analysis that follows will not apply to intersex people who identify as transgender.)

This feeling of being the wrong sex is not a passing fancy. Many who experience this powerful sense of dysphoria have tried to ward it off, or hoped to grow out of it. Many do! But many others find this sense of deep wrongness as persistent as it is pervasive. Someone like me, with a healthy male body and a male gender identity to match, can only imagine how upsetting it would be to find my body betraying me, growing parts where it feels like it shouldn’t while forgetting to include others it feels like it should. I would survive without my penis and testicles, but, if I were to lose them in an accident of some sort, it would be a profound loss, the hormonal changes would reshape my personality in ways I can’t predict, and I would be dealing with the changes and grief for a long time. Transgendered people attest that they live with something like that loss every day, that they’ve done so since childhood, and that they are constantly reminded of it in ways I would never have to be.

As Julia Serano wrote in Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Feminity:

I did not have the quintessential trans experience of always feeling that I should have been female. For me, this recognition came about more gradually. The first memories I have of being trans took place early in my elementary school years, when I was around five or six. By this time, I was already consciously aware of the fact that I was physically male and that other people thought of me as a boy. During this time, I experienced numerous manifestations of my female subconscious sex: I had dreams in which adults would tell me I was a girl; I would draw pictures of little boys with needles going into their penises, imagining that the medicine in the syringe would make that organ disappear; I had an unexplainable feeling that I was doing something wrong every time I walked into the boys’ restroom at school; and whenever our class split into groups of boys and girls, I always had a sneaking suspicion that at any moment someone might tap me on the shoulder and say, “Hey, what are you doing here? You’re not a boy.”

Take this, then throw in the hellacious hormonal chaos that is puberty, add the development of sexuality, and you’ve got a recipe for some serious cognitive dissonance and some genuine Grade-A suffering.

Trans people exist. Their experiences are relatively consistent (within a range of expected variation) across a huge range of first-person accounts. (Serano’s is worth reading. I’ve only quoted a slice of it, but would like to quote about ten pages of this book if it wouldn’t violate copyright law.) They collectively insist that their judgment about their gender identity goes beyond a mere feeling or intuition, beyond a judgment, and amounts to a true sensation as vivid as taste or proprioception. These accounts are difficult for cisgendered people to understand, but cannot be dismissed.

A common question the layperson asks at this point is, “What’s wrong here?” Are trans people afflicted with a mental disorder (which alienates them from their healthy bodies, akin to anorexia) or a physical disorder (such as an accident of birth where a female-typical brain or identity or sex-hormone receptor pattern developed inside an otherwise male body)? In other words, as the transition-skeptical Dr. Paul McHugh bluntly put it, is the fault in the mind or the member? Every mainstream American medical association used to answer, unequivocally, that this was a mental disorder. Today, every mainstream American medical association answers, unequivocally, that it is a physical disorder. It certainly seems to be the case that physical causes outside the reproductive system contribute to the brain’s sexual self-identification. Is that dispositive?

Fortunately, we don’t need to answer this question now. For now, it is enough to affirm that transwomen (and transmen) exist and that they suffer from this terrible sense of bodily alienation and/or dysphoria. This dysphoria, for many of them, has been intractable in the face of mental health treatment, but has been relieved, to greater or lesser extent, by changes that make their bodies (or at least their social presentation of their bodies; for example, how they dress) appear and function more like the sex that matches their “inner map,” their interior sense of gender identity. (These changes may range from meaningful but superficial changes in mannerisms to major surgical interventions.)

We can now offer a provisional answer to our original question:

Are Transwomen Women?

If we are using WomanA, the ancient definition, then, no, transwomen are not women. No matter what alterations they make to their social roles or their bodies to more closely resemble women, no matter the shape of the brain or the configuration of their hormones, no matter how intensely they feel they ought to be women, transwomen will never belong to the class of human beings who are, by their very nature, capable of pregnancy and birth. There are women who cannot become pregnant or give birth, but this is because their reproductive systems are either underdeveloped, aged, or diseased. Transwomen, by contrast, develop perfectly healthy reproductive systems—male reproductive systems. Under the ancient definition of men and women, transwomen are just men, and there is no surgery, no language, no amount of acceptance that can ever change that.

On the other hand, if we are using WomanB, then womanhood is defined by that “inner map.” If you feel interiorly that being in the boys’ bathroom is naughty but the girls’ bathroom is where you belong, that playing with Barbies is fun but playing with Hot Wheels is not, that you should wear dresses but not tuxedos, or that being sexually penetrated is just right for you while performing sexual penetration is just somehow not… then, regardless of your anatomy or biological capacity, your “inner map” has at least some correspondence to the “inner map” that our culture most frequently associates with the female sex! Transwomen typically report many or all of these experiences. Under the novel definition, that makes them women!

Under WomanB, no single person matches every sensibility and every stereotype on the “female inner map.” Moreover, that map is largely dependent on culture. Because of this, under WomanB, “womanness” becomes, not a binary, but a spectrum. People who mostly correspond to the “female inner map” are classed as women, people who mostly correspond to the “male inner map” are classed as men, and others may fall in the middle (identifying, perhaps, as non-binary, or bigender), while others may end up entirely perpendicular to the spectrum, off on some new frontier of gender performance (identifying, perhaps, as agender, or genderfuck, or even as an attack helicopter, as one transgender writer vividly depicted in a must-read short story). Indeed, under WomanB, some transwomen may have a more valid claim to “womanness” than butch lesbians, because butch lesbians often have significant divergence from our culture’s “female inner map”!

So:

“Are transwomen women?”

“Yes or no, depending on which definition of ‘woman’ you’re using.”

There you go, end of article, you can all go home now! Question answered! Here’s my closing quote!

…

…

…that’s not cuttin’ the mustard, is it?

“It Depends” Is Usually Enough

Okay, you may think “it depends” is a pretty trivial answer. You’re right! We aren’t much closer to a definitive yes-or-no conclusion now than we were a few pages ago, back when I was making up the Jamesian language and saying that “transwomen are women because comets are celestial bodies”!

But why would we ever expect or need a definitive conclusion? This tension between related definitions exists for a lot of words. It’s not weird. And it’s not normally a problem.

Is gravity a law? It depends on which definition of ‘law’ you’re using. If you’re using LawA, where a law is a rule of right conduct for people in a community, then of course gravity is not a law. (In fact, your government will be quite impressed with you if you find a way to break it.) But if you’re using LawB, where a law is a theoretical natural principle derived from particular facts about a given phenomenon, then of course gravity is a law after all.

Is Miyazaki’s Spirited Away queerer than Brokeback Mountain? Depends. If you’re using QueerA, where queer means “strange, odd, peculiar, or eccentric,” then, yes, Spirited Away‘s bizarre, unsettling fairy world is wayyyy queerer than some conventional Western gay romance. But if you’re using QueerB, where queer is defined as the antonym of “heterosexual,” then Brokeback Mountain is clearly queerer. (CHALLENGE: Say that ten times fast.)

Usually, when a word has multiple meanings, it’s clear from context which definition is being used, and we are all generally quite happy to accommodate ourselves to whichever definition is being used within a particular conversation. When I say that the U.S. Constitution is “the supreme law of the land,” someone might disagree with me by insisting that, in fact, decrees of the Supreme Court are America’s supreme law, or bring up Christopher Caldwell’s contention that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has supplanted the Constitution. But nobody will insist, through an extended argument, that I am completely wrong because the First Law of Thermodynamics is America’s supreme law and the Constitution isn’t even, properly speaking, a law.

Yet, when it comes to the word “woman,” that’s precisely what we see, on all sides: users of WomanA insist that users of WomanB are refusing to follow the science of biological sex, while users of WomanB insist that users of WomanA are bigots who want to force everyone into arbitrary gender roles. Not only has agreement been difficult; simple conversation has turned out to be nearly impossible. Some jurisdictions now require private business owners to use WomanA in deciding who can use the women’s bathroom. Other jurisdictions now require private citizens to use pronouns consistent with WomanB in their place of employment or face legal penalties.

This Is Odd

The thing is, there’s no obvious reason why WomanA and WomanB can’t exist in linguistic harmony, like LawA and LawB.

The concept of feminine gender performance, as opposed to female biological sex, is a genuinely useful one. In the past, we only had one word that meant both things, and it led us down some really awful cul-de-sacs. You can pretty easily read Bradwell v. Illinois (the case that denied women the right to be lawyers because their place was in the home) as an exercise in equivocation, in which the court correctly acknowledged the existence of feminine gender roles, but not only failed to acknowledge the contingent, culturally-inflected aspects of those roles, but actually conflated feminine gender roles (WomanB) with female biology (WomanA). This allowed the justices to reach an absurd conclusion: that having female biology entailed playing, always and everywhere, a feminine gender role.

For at least several centuries, all of society was structured around this equivocation. Because of it, wives had no separate legal existence from their husbands. According to 18th-century common law scholar William Blackstone, her “very being… is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated into that of the husband[,] under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs everything.” Whether this was actually true when Blackstone wrote it is disputed; that it became true as Blackstone came to be a revered legal authority, however, is certain, and this doctrine shambled on well into the 20th century. A wife in, say, 1830 New York could not vote; could not hold property; could not enter a profession; faced significant obstacles to obtaining an education; was subject to open discrimination by private parties; and was frighteningly vulnerable to being put into an insane asylum. Women were not even legally entitled to “separate but equal” treatment; equal rights under the law simply didn’t pertain to them. Any biological woman who deviated from these rigid gender-role expectations was understood to be defective.

The consequences were obvious, and often written about. What American high school student has not been assigned Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” or Kate Chopin’s The Awakening or Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God in English; or the Seneca Falls Convention’s Declaration of Sentiments, or Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women, or Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own in History? These works are consistent and persuasive on one central point: for quite a few perfectly sane, healthy, gifted women, the system made it suck to be female. This system—you might even call it a “patriarchy”—pathologized normal, God-given virtues.

Just because someone mothers her children (“to be a female parent,” a biological role) does not imply that person also mothers her children (“to treat a person with great kindness and love and to try to protect them from anything dangerous or difficult,” a social role). Although it can very reasonably be argued that these roles are related, society as a whole, for centuries, treated the two as identical, and the result was—bluntly—oppression. The development of the sex/gender distinction was a godsend for proper, natural equality and our ability to articulate it.

One hopes that, now that our language can accommodate both understandings of “womanness,” we would recognize the equivocation from a mile away and be able to avoid another Bradwell, or anything like it.

It’s not hard to imagine a world where both meanings of “woman” are taken fully aboard the English language and coexist in peace. Again, this is not weird. It would not be hard to sort out the context clues: If we’re talking about biological factors, like menstruation, it’s a clear cue that references to “women” refer to biological sex. When we’re talking about social roles, like being the more available parent, it’s a clear cue that references to “women” refer to gender performance.

This fluid use of the different definitions could even extend to pronouns. To an English speaker, it’s jarring, but I am told that there are a number of human languages that don’t make sex distinctions on pronouns, including Swahili and spoken Mandarin. (For our part, even we don’t make sex distinctions on second-person pronouns, which sounds just as jarring to Arabic speakers as the sentence “I love my wife; he is so kind,” sounds to us.) Prominent science-fiction novelists have been trying out various kinds of pronoun fluidity for decades, from Ada Palmer’s recent Too Like The Lightning quartet back to Ursula K. LeGuin’s (wonderful, highly recommended) The Left Hand of Darkness in 1969.

In a world where WomanA and WomanB weren’t at each other’s throats, you might easily navigate between them, saying something like: “Remember Jake? He used to work over in Accounting? Yeah, he fathered two kids, became a stay-at-home mom, and she seems really happy. She was absolutely doting on them at the park. But I still miss seeing him shirtless in the gym.”

Does that fluidity feel grammatically strange? Is it unfamiliar? Absolutely. But perhaps it’s not as odd as you think. I’m a romantic, and I love movies that make me cry. My wife is stunningly (jaw-droppingly) oblivious to romance and openly hostile to tear-jerkers. So, for years, we’ve joked that I’m “the girl in our relationship.” No one is confused when we make this little (very little) joke… and the reason the joke works is because there’s a sense in which it’s true. No one would suggest that my wife biologically fathered our kids or that I nursed them—to do so would insult the suffering she went through as a biological mother—but all our friends recognize the ways in which I am indeed “the girl in our relationship.” I’m sure that you can think of occasions in your life where you’ve switched between WomanA and some version of WomanB and back without a second thought.

Besides, imagine explaining this sentence to yourself just three years ago, in 2019: “Happy Blursday! Now quit doomscrolling, grab a quarantini and please keep social distancing.” In 2019, that sentence was meaningless in the English language. Now you know exactly what it means. Go back to 2005, and vast swaths of very normal lingo (like “OP” for “original poster” or “ghosting” for ending a relationship without a breakup, even “binge-watching”) didn’t exist yet. Conventions change! Language expands!

Yet, over in Gender World, none of this seems to be happening. Right now, you can get in rather a lot of trouble for saying, “transwomen are women in one sense, but not women in another sense.” It’s not like I’m breaking ground here. A decade ago, trans-inclusive feminist philosopher Jennifer Saul reached a conclusion nearly identical to mine… but then she rejected her own (correct) reasoning—and I quote her directly here—”simply [because] of political unacceptability.” For an academic, this is an astonishing admission.

Something has gone very wrong. The ordinary process of language evolution does not involve police arrests. We have never jailed anyone for refusing to use the Oxford comma, despite the obvious moral depravity of such recusants. And yet here we are.

The New Equivocation

I think, to this point, I have not broken any new ground or said anything especially controversial. I’ve given some notes on language, tried to explain two sides of a language debate clearly and evenhandedly, with appropriate citations, and pointed out that this particular language debate is unusually heated. I hope that I have succeeded. But now we come to the part of the article where I say something that I think is fresh… hopefully insightful, but certainly controversial.

I think the reason this particular language conflict is so heated is because of a determined campaign to erase womanA—the ancient definition, the biological female sex—from the English language and from the human imagination. There can be no cease-fire or modus vivendi at this time, because the existence of womanA as a concept that can be named offends womanB supporters—not all of them, not even close, but a critical mass of the influential ones.

J.K. Rowling’s great cancellation controversy started because of a tweet where she snarkily suggested that the English language has a word for “people who menstruate.” She was obviously referring to WomanA. For daring to suggest that WomanA is still a valid, useful definition in the English language, J.K. was roundly condemned by polite society, despite her impeccable left-wing credentials, and she faced intense financial pressure to recant her heresy. She chose to weather the storm (as few can, since most of us don’t have billions), but, even so, it seems safe to say that there will be no more favorable comments about Ms. Rowling in future episodes of Doctor Who. It’s now much less likely she’ll ever be knighted. Rowling has brushed off her critics so she can continue pointing out that biological women exist, and are a separate category from transwomen in some important respects. But lots of people—most people—care about their peer reputations. Under similar pressure, they would cave.

And, of course, that’s just what most of the great and the good are doing. CNN won’t say “woman” when “individual with a cervix” will do. The Brighton and Sussex University Hospital has replaced the word “mother” with “birthing parent” while handwaving “breast milk” into “human milk,” joining a growing trend—one that the United States Government, under President Biden, has now adopted. Planned Parenthood, of all places, now uses “pregnant people” instead of “pregnant women.” This is not mere politesse; it is now de rigeur for professors at medical colleges to insist that both gender and biological sex are socially constructed, and that men—in both the social and the biological sense—can become pregnant. As we have seen, this is false, and, moreover, it is exactly as false as the Supreme Court’s claim a century ago that women are incapable of practicing law.

If women and mothers can be erased from the process of childbearing and mothering, perhaps it’s not surprising that there is a growing “anti-genital preference” movement. This group contends that, if a person is sexually attracted to biological women (womanA), but not to everyone who identifies as a woman (womanB), including the ones with penises, that “genital preference” is a form of transphobia—an irrational and damnable bigotry toward transwomen, rather than natural attraction toward people you can make a baby with.

This movement is still mostly contained to academia and the fringe, but everything in this article was academic and fringe two decades ago. If you’re already erasing the very existence of biological sex difference with the phrase “birthing parent,” if Twitter already locks your account for “hateful conduct” if you write the words “Assistant Secretary of Health Rachel Levine is a man” (try it! it’s true!), then why wouldn’t you take the next step and label the basic biological building blocks of sexual attraction, coupling, and reproduction “hateful bigotry”? Sure, that erasure reduces all straight men and lesbian women to “transmisogynists”—but that’s a small price to pay for justice!

“Hey,” you ask, “are these semantic debates really where we should focus our attention?” After all, nobody died because Xavier Becerra won’t say “mother”. Meanwhile, culture warriors are fighting about book-banning campaigns and about whether transwomen should be admitted to certain bathrooms or certain sports. Prisoners (both transwomen and “biowomen”) face heightened risks of rape, and trans activism is increasingly coming into direct and (for all parties) utterly terrifying conflict with parental rights. Why bother with semantic arguments about nothing when I could be talking about all that?

Normally, I agree. 99% of semantic arguments are about nothing, and I avoid them. I spent a long time (and many drafts of this article) trying to pull my usual trick, where I agree to all the labels my opponents assign so I can move on to discussing the actual substance.

But, in this case, the semantics is the substance.

Do you think conservatives actually care about women’s sports? Maybe some have been persuaded to care, but, come on, the median conservative spent forty years making jokes about the WNBA’s bad ratings and wondering out loud why anyone bothered with women’s sports above the high school level at all. But women’s sports provide a site where conservatives’ broad concern about the erasure of biological sex is highlighted: there is an objective, undeniable, and incredibly obvious biological difference exposed by women’s sports that is absolutely not a “social construction” or “performance of gender.” If our society can pretend WomanA has no meaning in women’s sports, then it can erase WomanA from anywhere and anything. So that’s where gender conservatives plant their flag.

Meanwhile, in Canada, trans activists have been working for a number of years, with modest success, to defund and close a women’s shelter, with a side of occasional vandalism. The reason for their opposition is that the shelter is “trans-exclusionary,” because it identifies as a women’s shelter but does not serve all women (womanB). The shelter responds that it does indeed serve all women (womanA), including transmen. There are ample local resources for transwomen facing domestic violence or rape, and the shelter refers transwomen to those resources when they get the call—but their shelter’s mission is to serve women in the sense of womanA, rather than womanB. Their decision to act as though this distinction exists and can matter in some contexts, even in progressive Vancouver, means this is where gender progressives plant their flag.

The semantics is the substance.

Trans advocates routinely accuse Abigail Shrier and Ryan Anderson of being “dangeorus and harmful” and of calling for the “extermination” of trans people, leading even the American Civil Liberties Union to demand the forcible suppression of their work. I hope it goes without saying that neither Shrier nor Anderson call for anything even remotely of the sort. You can read their blogs, you can read their books (I’ve read Anderson’s). They very clearly oppose anti-trans persecution of every kind, and (it should go without saying) they find the idea of “exterminating” trans people as reprehensible as exterminating any other group.

However, Anderson disagrees with the claim that transwomen are (in every possible sense) women, and presents his reasons for thinking that way. Shrier disagrees with the claim that teenagers’ self-identified genders should always be taken at face value. The ACLU and the rest of the movement holds that this disagreement, by itself, is a so-called “act of violence” which should be banned.

In other words… the semantics is the substance.

In the past, conservatives controlled the commanding heights of culture through media, academia, journalism, and politics. Many of them insisted on equivocating between womanA and womanB by subsuming feminine gender performance totally into female biological sex. Not all of them did this, not even close… but a critical mass of the influential ones did. You see it in Bradwell and in the anti-suffragette movement (which, interestingly, often cited evolution, rather than religion, to support the equivocation). Even as recently as much of Phyllis Schlafly’s writing and speaking, you see this conflation. They did this in the name of societal safety, trying to hold gender-based chaos at bay through what many of them surely realized was an oversimplification. Yet their good intentions were all it took to build the systems of female oppression that Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Myra Bradwell fought against.

Today, progressives control the commanding heights of culture. Rather than eliminating the equivocation, many of them (not all, not even close, but a critical mass) have reversed it, by insisting on subsuming female biological sex totally into feminine gender performance. They do this in the name of individual safety. They point to high rates of suicide and mental illness among trans people, blame these high rates on the “transphobic” lack of “acceptance”—typically characterized as treating WomanA as being, in some respects, distinct from WomanB—and then accuse those who continue using WomanA of promoting hate. The systems of oppression that result from these good intentions are still in progress, but their contours are starting to come into focus. There’s a reason the title of this article is in Latin: I believe Latin is likely evade the automated censorship algorithms that, for the most part, determine the boundaries of human discourse in 2022 America. Those algorithms are not fans of discussions that even raise questions about the progressive account of womanhood.

Yet the language won’t be able to accommodate both meanings of “woman” until we stop trying to erase either one of them.

If “WomanA” Did Not Exist, English Would Be Forced To Invent Her

Every language in the history of humanity has had a word meaning “the sex that bears offspring.” This is the sex that has babies. It’s also the sex that bleeds each month. It’s also the sex that has vaginas, and boobs, and which produces “human milk.” It’s the only sex to get cervical cancer, thus the only sex that needs to be vaccinated against it. It’s the only sex whose natural estrogen almost always dominates over androgen. It’s the sex that is, for whatever reason, more prone to strokes, but less prone to dying of COVID-19.

This is not simply a series of coincidences. The “birthing person” in a relationship always has ovaries, a uterus, a birth canal, and childhood memories of having a first period. This is because birth is linked to a complex biological system defined by sex—in English, we even call the act that activates this system “having sex.” It’s weird that this needs to be said, but the people who say “birthing person” seem to want everyone to think that it’s all just astronomically unlikely happenstance that so many “birthing persons” turn out to carry tampons (a biological marker of sex) in a purse (a social marker of gender).

Nor is this some minor difference blown out of proportion by ignorant people, like hair pigment or melanin. Women’s biological differences from men are substantial, they are not socially constructed, and they mean that, inherently, women face both unique challenges and unique opportunities across a broad swath of their lives, compared to men.

Yes, it is still disputed which specific differences between men and women are biological and which are not, and there is a lively “nature-or-nurture” debate. But some differences are clearly biological. No reputable psychologist takes the “nurture” side of the “nature-or-nurture” debate when the question is, “Why does this person have a uterus?”

Remember back at the start, when we looked at a lake and called it “water”?

And then remember we spoke of a tyranny that might demand we stop talking about the lake, for political reasons? To pretend it’s filled with milk, or that it’s not really there?

Perhaps our hypothetical tyranny isn’t quite that bad. Maybe we are allowed to acknowledge the lake water, but only when we are actively drinking it (during which time we are allowed to call it a “thirst-slaker”) or when it’s flooding the village (at which point we are instructed to call it in to 911 as an “enfloodening substance”). But our inability to name the thing makes it impossible for us to see the thing, which in turn makes it impossible for us to study the thing, to know the thing, to interact with the thing. In a society where “water” is erased from the language, recognized only through facets of itself rather than as a unified whole… well, let’s just say that society is going to have a lot of trouble building bridges, or hydroelectric dams, or wells, or raising crops, or putting out fires.

There are similar consequences for a society where “woman” (in her ancient, biological definition) is suppressed and replaced by “birthing person” and “people with periods,” and so on. Language is arbitrary, so we don’t need the word for “offspring-bearing sex” to be “woman.” We could reserve the word “female” for the biological (womanA) sense of womanhood while leaving “woman” to be all about gender performance (womanB). Maybe we make up a new word to talk about women in their biological essentials. Or maybe we eventually all chillax and just start using both versions of “woman” according to context clues, as I suggested earlier.

But we need a word for “offspring-bearing sex.” We can’t keep talking about “people with cervixes” and “birthing parents” as if those were entirely separate categories of people—not if we expect to continue having a comfortable relationship with reality. J.K. Rowling is a wordsmith, an actual genius at coining nouns (my undying admiration of the words “splinch,” “knut,” and “muggle” is a whole separate future blog post), so it’s unsurprising that she noticed when a necessary noun had gone missing. English-speakers will always identify this gap and will always fill it with a word—even if the local commissar gets mad at them for acknowledging the existence of females. It’s no different from when the commissar gets mad at you for calling the “potential enfloodening substance” “water” instead of “milk.”

We need WomanA.

A Definition in Want of a Grounding

We’re not the only ones who need WomanA. WomanB needs her, too.

Let’s take another look at WomanB, the “novel definition.” According to that definition, to be a woman is to have a woman’s “gender identity” (rather than a woman’s gestational ability). In turn, gender identity is defined as an “inner map” which corresponds to the maps of other people who have a woman’s gender identity. But, hold up, that looks circular: we’ve just defined female gender identity by referring to female gender identity. It’s like if you asked, “How do I join the lady club?” and I answered, “You have to think the same things the other members thought when they joined the lady club.” Your next question is liable to be, “So what are those things?!”

WomanB does give us an answer: according to Jenkins, in order to join the “female gender identity” club, you have to think the same way as the people who have been “targeted for subordination” based on “actual or imagined… evidence of a female role in biological reproduction.”

But look at that last term, the foundational term that keeps the rest of the definition from collapsing into circularity: “female role in biological reproduction.” In other words… WomanA. In this very advanced work of WomanB feminism by a well-regarded WomanB feminist, we still find the ancient definition doing important work.

Jenkins and trans-inclusive feminist theory seem to find this embarrassing, and bury it beneath several layers of theory, oppression, and subjectivity… but, in the final analysis, the definition of WomanB is incoherent without eventual reference to “the female role in biological reproduction.” This appears to be true across the board. I have not yet been able to find a coherent, non-circular definition of gender identity that avoids referring to pregnancy or the bodies that make pregnancy possible. (Jenkins’ version does a much better job of hiding it than most.) A reasonable conclusion to draw: WomanB, and the entire concept of “female gender identity,” cannot mean anything without eventually talking about vaginas and ovaries and pregnancies. Which means WomanB depends upon WomanA… and the reverse is not true.

I’m told that observing this is a form of “biological essentialism,” and that that’s very bad. However, I don’t see a strong reason to be so worried about the shadow of “biological essentialism.” Just because WomanB depends on WomanA doesn’t take anything away from WomanB’s independent value as a really useful and separate definition.

Take the word “magnetic.” It has (broadly) two meanings. MagneticA refers to a thing’s power to attract (or repel) other objects based on differential motion in electric charges—a physical, observable property of reality that is in no sense socially constructed. MagneticB refers to a person’s power to attract or influence other persons with her charisma—a reality that is very much socially constructed and socially mediated. MagneticB (like WomanB) makes no sense without referring back to MagneticA. So MagneticB depends on MagneticA for coherence, while MagneticA depends only on reality itself. But nobody walks around trying to find Zendaya with a compass, because that would be a stupid equivocation. MagneticB is a good and useful term that is related to, but not identical with, MagneticA.

We will know the gender wars are over when we are as comfortable with the dual, complementary meanings of WomanA and WomanB as we already are with MagneticA and MagneticB—when nobody insists any longer that one of them should be erased from the English language and the human imagination—when we can all openly talk and (yes) argue about how they relate (and how they don’t relate) without anyone in the conversation fearing for their safety, their livelihood, or their happiness.

Some Practical Implications (or: the Lack Thereof)

When you started reading a 13,000 word blog post on gender identity, you probably thought you were going to get something useful out of it—a devastating rebuttal to people who disagree with you about women’s sports, maybe. Psych! You just read 13,000 words about the English definitions of “woman,” in which I affirm both of them, and that’s all you’re getting!

I can hear some of my conservative friends already. “James, are you alright in there? You just spent twenty-five pages refusing to commit to anything practical, on maybe the easiest issue in a generation. Blink twice if you’re being held hostage!” To which I say: hey, if I were a hostage, would I really go out of my way to support Undesirable Number One, J.K. Rowling?

Indeed, I think I have made some eminently practical commitments. If the current debate about trans justice is, at its core, a semantic argument, then getting a firm grasp on the language (and its underlying realities) is most of the ballgame. It seems to me that the most dramatic divisions, the ones that have made conversation impossible, melt away if all sides can agree on some core claims.

I suggest that a solid core to build out from has three “planks,” which I have tried to articulate in this piece: that biological females exist, that feminine gender performance exists, that transwomen exist, and (therefore) that the correct answer to “are transwomen women?” is “depends whether ‘woman’ means ‘female’, ‘feminine’, or something else in this context.”

Even if we all accept those premises, there is still plenty of room for practical disagreement. Indeed, someone who accepts these ideas could end up anywhere on a broad spectrum: you might conclude that (while not identical) sex and gender are closely, innately linked (as Prudence Allen thought and Abigail Favale thinks); you might conclude that connections between sex and gender are pretty arbitrary social constructs mostly fit for smashing (as self-id’d “YouTube SJW” Laci Green thinks and Anne Fausto-Sterling seems to); or you might land somewhere in a modest middle (as Leah Libresco Sargeant seems to have done, and as Scott Alexander certainly has).

Nothing about the claim, “Transwomen are femmewomen but not biowomen” implies specific answers to questions about women’s sports, bathrooms, book bannings, gendered dress codes, or the appropriate medical treatment for trans people. All those topics intersect with other questions, and this article hasn’t dealt with those intersections. All this article attempts to do is put everyone in the same ballpark at the start of those discussions, and perhaps dismiss some of the dysphemisms (“assigned female at birth”; “men invading women’s spaces”) that get in the way of having them. Specific topics will still need a great deal of further examination.

Let’s consider how this examination might work on just one battlefield, one that (to both sides) seems easy, like it should be a simple layup we can resolve in two sentences and a hearty handshake: the pronoun controversy.

Pronouns

The meanings of English-language pronouns are currently very unstable.

In the past, pronouns (when applied to people, rather than, say, boats) have referred exclusively to biological sex. “She” designates “biofemale”, “he” designates “biomale” or “impersonal default”, and “it” designates non-persons. This ready division of the entire human race into two-and-two-thirds categories (categories which define and bound many of our relationships) has many advantages and conveniences—or so the argument for this approach goes. It is unclear where the rainbow of intersex people are supposed to fit into this schematic, but the language didn’t really know about intersex people historically, and today’s hardline supporters of “biopronouns” tend to assign all intersex people to one of the two sexes anyway.

In recent times, in parallel with the rise of WomanB, pronouns have been troubled. Supporters of the “novel definition” contend that, rather than biological sex, pronouns ought to designate gender identity. Since gender-id is far more subjective than biosex, the only way to learn someone’s “correct” pronouns in this system is to ask that person. (That person will have presumably selected appropriate pronouns after a process of self-reflection.) This pronoun system is better than the old system (according to its supporters) in part because it marginalizes biosex, which they believe ought to be be marginalized, ignored, erased from the language, even denied outright. As we’ve seen, that’s a bad instinct.

However, there’s a good instinct, too: supporters believe this “affirming” pronoun usage is better at protecting our trans brothers and sisters. Many trans people feel a great deal of emotional pain related to their biological sex, which gives them a profound, sincere desire not to be reminded of their connection with it. If we don’t want to hurt trans people, the argument goes, we should use the pronouns that correspond to their chosen social roles rather than their unchosen birth anatomies (which some trans people have even surgically removed in order to relieve powerful feelings of dysphoria). Failure to do this (the argument goes) leads directly to trans suicide.

Moreover, supporters argue, if we can call school buildings (which have no genitals at all) “she,” surely we can politely call someone who has a penis but wears dresses “she”—especially if it is that person’s strong and clearly expressed preference.

Biopronoun supporters retort that we call schools alma mater because of a specific analogy to biological sex; schools nurture and birth us into the life of the mind and the adult world in much the same way our mothers birthed us out of the womb. It’s a literary device meant to enrich, but not contradict, reality.

Even after both sides acknowledge that sex and gender both exist and both matter, these arguments are both viable. I will not attempt to resolve them here. If I have done my job well, you cannot tell which one I favor. Indeed, earlier, I suggested a future middle ground, where pronouns are fluidly exchanged based on context cues, and you might refer to a biological female as “she” (biologically female pronoun), “him” (socially masculine pronoun), and “she” again (but this time it’s the socially feminine pronoun), all in the course of a single sentence. Yet this is hardly the only reasonable outcome. Even after acknowledging the existence of both sex and gender, both sides can (and do) make strong arguments on behalf of “affirming pronouns” or “biological pronouns.” In the long run, we may collectively decide to make pronouns exclusively refer to one of them.

An Interim Approach to Pronouns

It will take a long while for us to reach a new stable equilibrium on pronouns, and I do not know what that will finally look like. Knowing how funny language is, I suspect it will not look quite like anything anyone today expects or wants. As long as we end up with a shared meaning for pronouns that reflects something true about the world, the same way the word “water” reflects something true about a lake; as long as we retain a vocabulary that allows us to talk about different aspects of reality when needed; we will be okay.

Unfortunately, we don’t live in that world today. Today, pronouns are not just contested; they’re polarized.

If you use “he/him” pronouns on a transwoman, even after learning that this person is trans and identifies as “she/her,” you implicitly and unavoidably affirm the hardline ontological position that biological sex implies social role, and that this transwoman’s biological maleness is all that should or could matter to anyone. You imply that you think this person is a raving lunatic and that you don’t particularly care if this person lives or dies. You may not intend to communicate any of that, you may not believe most of that, you may not agree there is any logical connection whatsoever between the pronoun and that set of claims… but words don’t mean what we individually want them to mean; words bear the meaning that the culture as a whole has given them. And, currently, our culture has given “he/him” this meaning in this context. If you use these pronouns in this way, a typical English-speaking audience will (fairly or unfairly) construe you to mean all these things.

On the other hand, if one refers to a transwoman with “she/her” pronouns, then one implicitly affirms the ontologically extreme position that social role implies biological sex, that transwomen are truly female in every conceivable sense of the word, and that anyone who denies a transwoman this pronoun is a bigot. Again: whether you believe this or not, whether you want to communicate it or not, that is, right now, today, the culturally-assigned meaning of “she/her” in this context: a full-bodied affirmation that biological sex should be hidden, memory-holed, and un-named. If you use these pronouns in this way, a typical audience will (fairly or unfairly) construe you to mean all these things.

These are the only options, and they are both terrible. Polarization sucks, doesn’t it? (I feel the same way about voting these days.) How to muddle through while the language sorts this all out?

In general, I think that we are morally obligated to be honest in our speech. We should be tactful and kind, but we must never deliberately communicate falsehoods through our words—not even to be tactful or kind. There may be exceptions for certain games (like poker), or extreme circumstances where the Nazis are at your door asking whether you’re hiding any Jews in the house… but I don’t take even these narrow exceptions for granted. It seems to me that the overriding purpose of humankind is to discover the Truth (whatever it is) and to live by it once it is found; there is simply no other hope for human happiness, now or ever, besides Truth. To lie, by asserting something one knows to be formally false, is an unjustifiable breach of ethics.

I may be more absolutist about lying than most, but I think the vast majority of people agree that lying is bad. Certainly most of us agree with Orwell, who argued that consistent, ideological lies (especially lies that corrupt language) imperil all society; with Solzhenitzyn that those same lies corrode our own souls; and with Al Franken that we wish people would lie less.

That desire not to communicate untruths leaves us in a bit of a pickle with these polarized pronouns. Both approaches communicate some bad stuff: the first, a striking lack of charity and an ontological claim that is, at a minimum, overstated. The second is more comforting, but they don’t call them “affirming pronouns” for nothing—by using them, you affirm a slate of claims about sex and gender that are not only untrue, but, in our present moment (as we have seen), sometimes exclusive and even oppressive.

So I don’t use either. When I find out someone would like me to use affirming pronouns instead of biopronouns, I ordinarily stop using pronouns altogether. I must not be unkind, and I must not lie. As I see it, I can’t use pronouns without violating one of those moral rules, so I can’t use pronouns, the end. You’d be surprised how easy it is to do this—zero percent harder, sometimes easier, than actually changing the pronoun that comes to mind when you are talking with that person. I like to think the people I’m talking with don’t notice. But in case they do notice, I thank my friends for respecting me enough to accept my approach anyway. Perhaps they see that I am trying to be true to myself just as they (I know) are trying to be true to themselves. Perhaps they’re annoyed but just don’t think it’s worth fighting about. Regardless, I am grateful.

Sometimes, if we form a certain kind of friendship in a certain kind of group, they start to get a sense for what I think about culture and religion and politics, and then I become much more comfortable using affirming pronouns—because, by that point, they know that I don’t affirm the whole panoply of novel beliefs about gender. I can then use the pronouns without asserting anything false, and without misleading those around me. There are other exceptions to my rule as well, dictated by prudence and a well-formed conscience. For instance, if I’m an ER doctor trying to save the life of a teen transgirl who has just attempted suicide and is dying before my eyes, I think it’s prudent to just accept her pronouns and focus on saving her life.

Most people on both sides seem to think the pronoun problem is utterly simple, but I find pronouns very knotty indeed. This is my approach to them, hopefully a temporary approach until society reaches a less polarized settlement. I don’t think it’s the only possible approach that a reasonable person might adopt in good conscience, even if they agree with me on my three “planks.” I have friends who agree sex is real but who simply don’t agree that using affirming pronouns implicitly denies the reality of sex, so they use affirming pronouns. I have other friends who agree we shouldn’t be cruel, but who simply believe honesty requires them to clearly reject (and not merely evade) the ontological errors of the current moment, so they use biopronouns.

Meanwhile, for people who disagree with my three planks—as some reasonable people do—Katy bar the door, because we’re definitely not going to see eye-to-eye about pronoun use. That’s okay, as long as we all strain to our utmost to treat each other with respect and try (as best we can) to gently guide one another toward what we think is the Truth. Eventually, the English language will stabilize again, hopefully around a good pronoun system, probably not, but it will stabilize, and we just gotta get there.

Bring It Home, John

So that was four pages about pronouns, the “easy layup” topic. Imagine how long we would have needed before we could draw any useful conclusions about the WPATH guidelines for prescribing puberty blockers to children or gendered dress codes in the Aimee Stephens legal case. We’d have to introduce actual evidence, and then argue about how to interpret that evidence, and we’d be here until Christmas 2026. This stuff is complicated!

Again, those disagreements will happen even if we have all agreed to acknowledge the importance of both “gender” and “sex”, to stop trying to scrub them from the English language and/or daily life. That agreement seems very far off in our society at large.

But hopefully, you see in the pronoun test case that my argument (“biological sex and social gender performance both matter”) is just a foundation. And, hopefully, that test case also suggests how you might begin carefully working out for yourself the details of what all this means in the real world.

Words are tricky things. Nature is even trickier. People are trickiest of all, and this, more than anything, has led us into the blind alley of our current gender wars. We cannot abolish reality (much as some would like to), nor can we reduce it to a rigid, all-encompassing binary (much as some would like to). We can only do our best to come up with words that accurately describe reality, in all its uncomfortable complexity and its painful limitations. If we hope to succeed in that project, both the ancient, biological definition of “woman” and the novel, socially-constructed definition of “woman” will be necessary.

And then, when our arguments are settled, our policies are set, and our society is content with the settlement, we can, at long last, on that glorious day, get back to fighting about whether a chicken wrap is a sandwich.

(The answer is that sandwiches aren’t real. But that’s another blog post.)

Next Time on De Civ: I’m working on a piece about abortion and the 13th Amendment, but I think a nice sedate Worthy Links would be a good respite next week, don’t you? I also have a book review to finish for another publication.

UPDATE LOG: Unsurprisingly, there have been minor changes or corrections to this article since its publication. For complete transparency, here they are:

4 April 2022: A reader informs me that you can write Japanese the sound “mana” as まな in the hiragana system (although this is not a word), or, treating it as a foreign loanword, マナ in Katakana. I have made no changes to the body of the article, but thought it was an interesting note.

5 April 2022: I originally misspelled Caitlyn Jenner’s name as “Kaitlyn Jenner.” The error has been corrected in the body of the article.