Some Constitutional Amendments #3

NOTE: This post was originally published at my Substack. The footnote links go there instead of to the bottom of the page.

Many writers propose constitutional amendments in order to demonstrate their fantasy vision of the perfect regime. In this series, I propose realistic amendments to the Constitution aimed at improving the structure of the U.S. national government, without addressing substantive issues. Today’s proposal:

AMENDMENT XXX

Section 1. If a state elects Representatives by electoral districts (whether its entire delegation or only a portion), all persons in the state shall be included in exactly one such district; each district shall elect an equal number of Representatives; each district shall be contiguous; the smallest district shall have at least nine-hundred-ninety-nine persons for every thousand persons in the largest district; and the average straight-line distance between each person’s residence and the geographic center of that person’s district shall be the minimum known to be possible at the time prescribed by state or federal law for the determination of districts.

Section 2. If a state elects multiple Representatives from any single district, it must use proportional representation to elect Representatives in all districts. Congress may enforce this section by appropriate legislation.

Section 3. Congress may not otherwise interfere with any state’s apportionment of districts for election to the House of Representatives, or its choice of plurality, majority, proportional, or mixed voting systems in elections to either house of Congress.

Perhaps the Founding Fathers’ biggest mistake was that they expected no political parties.

The Founders believed political parties were very bad, and also believed that (in a healthy republic) political parties would never arise. They were very clear that their system would not work as intended if political parties (or “factions”) arose.

Oops! Factions emerged almost immediately, making this one of the first pieces of the Founders’ Constitution to fail. A mere eight years after the Constitution was ratified, the nation was riven by one of the ugliest, most partisan presidential elections in its history, the Jefferson-Adams election of 1800. This was the fruit of America’s First Party System. Today, we are on the Sixth Party System, possibly in transition to the Seventh. What we’ve never had1 is a No-Party System. With 21st-century hindsight, we now know that parties emerge automatically in democratic systems. This is because people disagree about things, and naturally form coalitions with others who share similar (but not identical) interests in order to mutually advance their interests.

The Constitution instructs that states be given Representatives based on their population. It further instructs that all Representatives be chosen by popular election. Beyond that, the Constitution entrusted state legislatures to decide all the details of elections for Representatives, although Congress retains broad powers to supervise the states’ decisions.

If state legislatures are composed of dozens of independent voices all trying their best to serve the best interests of their district first and their branch second, then this (probably) works quite well. State legislatures may settle on a wide range of electoral systems that work reasonably well, and they will draw any electoral districts with roughly equal population2 based on county lines and city borders. Any individual legislator who tries to wrest an unfair advantage for herself or her district will get outvoted by the rest of the legislature.

…but if state legislatures are composed of two political parties, one of which has majority control, then Katy bar the door! The political party members will work together in the interests of the party first, their districts second, and their branch of government some distant third. They will choose an electoral system and draw districts that maximize the strength of the party, and no one can stop them.

Gerrymanders: They’re Bad!

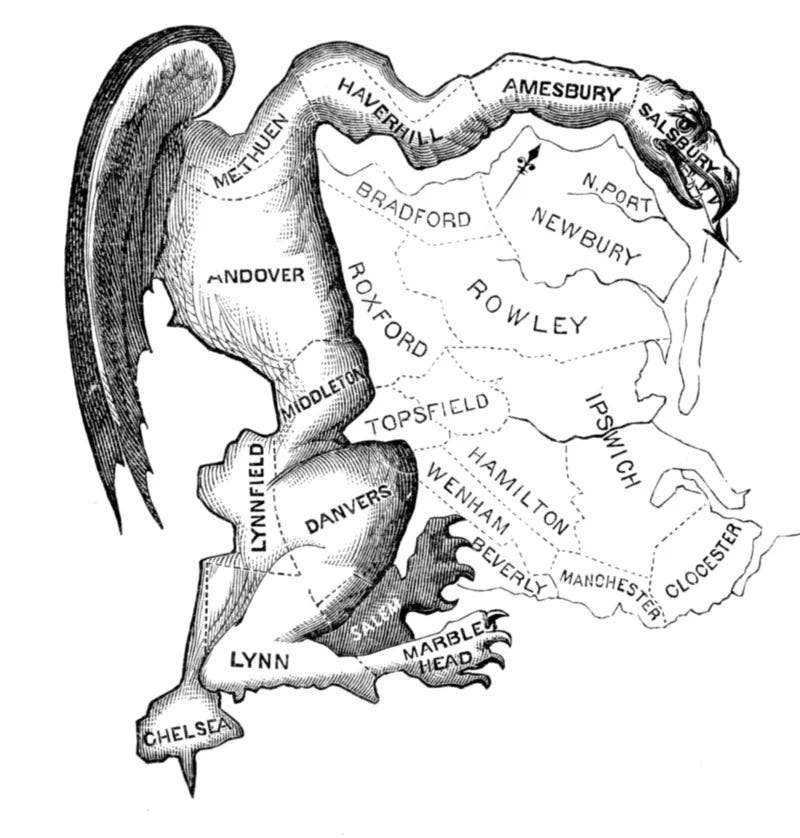

In 1812, the word “gerrymander” was coined.3 The word immediately went national, because, a mere 20 years after the Constitution was ratified, gerrymandering was already widespread. It just hadn’t had a name before! You’ve all seen the original cartoon, but it’s a good one, so here it is again:

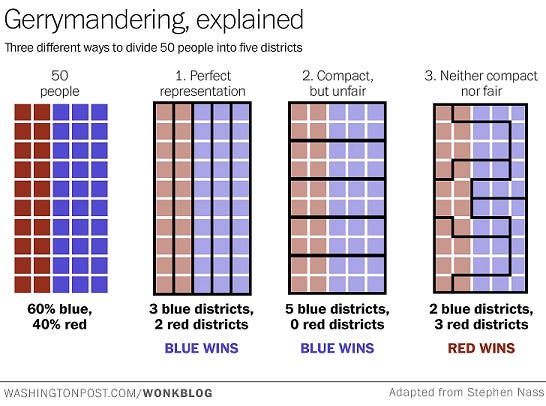

Political parties wiggle and bend their districts however they need them to bend in order to elect a greater proportion of the legislature than their overall vote share would imply they deserve. Gerrymandering has been a continuous feature of our political system for over two centuries. The Washington Post produced a useful graphic a few years ago to explain how it works:

With computer assistance, gerrymanders have become ever more effective. Both parties do it and always have. In fact, for most of the 20th Century, Democrats drew by far the most effective gerrymanders. It was only when Republicans took control of the 2010 redistricting cycle, just as computerized gerrymandering came into its own, that stopping gerrymandering suddenly became a democratic fundamental to the Blue Tribe.

Today, you can easily pick out red or blue gerrymanders throughout the country. However, for my money, the most offensive map is the Wisconsin State Assembly’s. In the 2018 election, the Democrats won 53% of the total vote in the state, beating the Republicans by 8 points and scoring a solid outright majority in the statewide popular vote… but the Democrats only got 36% of the actual seats in the Wisconsin State Assembly. Republicans, who lost the election decisively, ended up three seats sort of super-majority control in the Assembly that year.

Longtime readers know how passionately I believe that democracy needs to be constrained. But, reader, if you have a popular election and the clear outright winning party ends up with barely a third of the available seats, you dun screwed up. That’s not “constraining” democracy. It’s not having democracy.

Of course, if Wisconsin Democrats had won enough votes, no gerrymander could have stopped them. If they had won 60%-40%, they would have won a majority of seats. If they had gone much beyond that, the Republicans’ gerrymander would have converted to a dummymander, awarding Democrats a disproportionate number of seats. In our polarized age, however, these kinds of swings are very rare. Map-drawers know that.

Again, this isn’t because Republicans are unusually evil or anything. The current partisan asymmetry in redistricting is largely because Republicans got lucky in 2010. Their luck will, inevitably, run out. Democrats first tried to ban partisan redistricting through the courts, but, when that failed, they (quite rationally) embraced partisan districting in order to counter the GOP. They’ve proved quite adept at it in the 2020 cycle. What happens in 2030 is anyone’s guess. That makes the 2020s an ideal time to put a stop to gerrymandering, once and for all.

I trust this is uncontroversial. I have never heard a principled defense of partisan gerrymandering. Everyone seems to know that it’s bad, and that it’s a double-edged sword. It’s just that neither party can unilaterally disarm. The closest anyone comes to defending gerrymandering is that it’s been around since the Founding (true), Democrats’ current outrage over gerrymandering is selective and hypocritical (true but the Republicans will do the same whenever the pendulum swings back), and that gerrymandering can’t be eliminated without reconfiguring our constitutional order.

So let’s reconfigure our constitutional order! That’s what amendments are for!

Current Districting Law

The simplest option would be to simply enshrine our current redistricting law in the Constitution. That may sound tautological, but a lot of current redistricting law was either made up by courts in the 1960s—sometimes in flagrant disregard of the Constitution4—or flows from that court-made law. Much of the rest comes from Congressional statutes, which are good, but could be repealed relatively easily by a sufficiently large and determined majority. If we think our current redistricting law offers good guidance, it might be wise to give it an actual grounding in the Constitution, rather than counting on bad precedents and good statutes lasting forever.

To summarize a lot of law very quickly, the law currently says that Representatives must be elected from congressional districts that are:

- Contiguous: you can’t split the district across different parts of the state; all parts of the district must actually connect. You never thought of non-contiguous districts, didja? But some clever gerrymandering legislator did.

- Comprehensive: your districts have to include everyone in the state. You can’t decide you just don’t like the voters in, like, Duluth or something and exclude the entire city of Duluth from your electoral districts. Everyone gets to be in one (and only one5) electoral district.

- Compact: the district can’t be in a weird, wiggly, elongated shape (like Mr. Gerry’s original gerrymander). Mathematically, this is extremely difficult to define precisely, but people know a non-compact district when they see it.

- Equal population: the district can’t have more or fewer people in it than other districts. Courts allow very little deviation from this, requiring a “good faith effort to achieve absolute equality,” and striking down any maps where the difference between the largest and smallest district’s population is more than 0.8% of the population of the average district. (Even that was allowed only with special justification.) Incidentally, meeting this requirement is really quite challenging. Try it yourself sometime.

- Racial representation: the district map, as a whole, must provide reasonable and proportionate representation to racial minorities that have distinctive voting patterns (think Black voters, who are largely loyal Democrats but who live in strong Republican states). This rule (somewhat perversely) requires gerrymandering to create a proportionate number of “majority-minority” districts, but makes sense in the context of rampant Jim Crow anti-Black gerrymanders.

- Single-member: each district must elect one and only one Representative. Multi-member districts, where each district would elect multiple Congressmen, and at-large districts, where the entire state voted on all its Congressmen, have mostly6 been outlawed since the 1840s. The problem with multi-member and at-large districts was that parties would use them to give themselves disproportionate power. For example, in a state that’s 60% Democrat and 40% Republican, you could have district-based elections, but Republicans are probably strong in some parts of the state and are likely to win at least a few seats. But if you have a statewide, at-large election, you can ensure that Democrats win every seat! Southern Democrats also contemplated using at-large Congressional elections to suppress Black political power after the Civil Rights Act passed.

- Community of interest: this is more of a nice-to-have than a requirement, but courts and legislatures are generally supportive of efforts to keep “communities of interest” (towns, counties, neighborhoods) within the same district. If one map splits a town’s voters into three districts, but another map keeps the whole town in one district, then, all else being equal, everyone would prefer the second map. However, this criterion is vague, subjective, and is always the first criterion sacrificed in order to make the others work.

If you’re trying to build a federal democracy where voters of all persuasions from every state are represented fairly in the People’s House of Congress… these are mostly pretty sensible rules! Even if some of them were made up out of whole cloth by an unelected, unaccountable Supreme Court in the 1960s, they’re (mostly) worth keeping.

Redistricting Commissions Considered Harmful

One popular proposal for ending gerrymandering is to put map-drawing power in the hands of so-called “independent redistricting commissions”, like the one they’ve set up in Arizona. The idea is, you set up a commission that is either non-partisan or has equal representation from both parties (plus maybe independents). You put wise, fair, and impartial people on it—people who can be honest and concerned for the whole state, because they don’t have to worry about winning re-election. Then you give them the districting criteria listed above and tell the commissioners to use those rules to draw fair maps. The commission’s maps then become the law automatically, even if the partisan legislature wants to gerrymander instead.

This sounds great until you think about it for a few minutes.

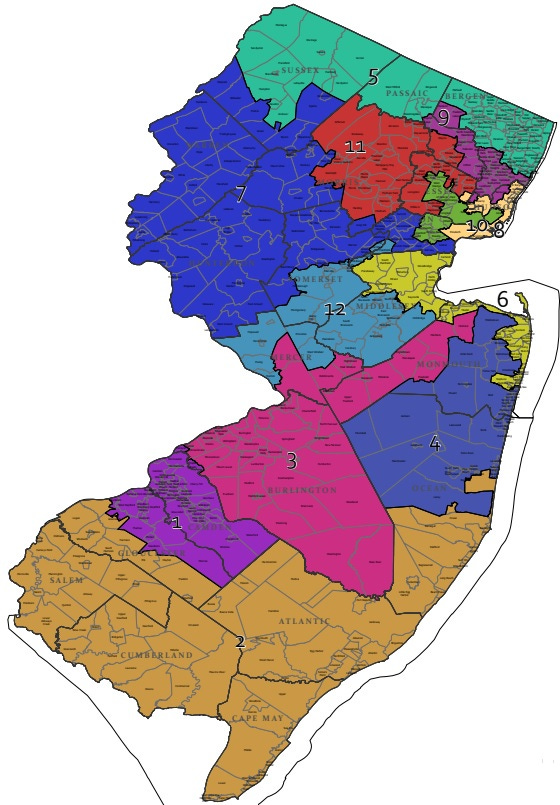

As soon as you set up a non-partisan commission with the power to make or break the power of both political parties in a state, what’s the first thing both political parties are going to do? That’s right: try to take control of the commission. There are a number of ways of doing this. On a non-partisan commission, you just appoint people whom you know privately to be “on your team.” On a partisan commission, you either try to appoint clandestine partisans to any “independent” seats, like in New Jersey, or you try to exploit factions in the other party to your advantage.

You can’t avoid this by making the process for appointing people to the commission non-partisan, either. Under modern polarization, there is no such thing as a non-partisan appointments process. Everyone in proximity to government has partisan views. Handing the appointment power to, say, the “non-partisan” government bureaucracy would simply hand control of the commission to Democrats, who overwhelmingly dominate the bureaucracy. Exactly this happened in California, despite fairly elaborate anti-partisan firewalls. Having commissioners appointed by, say, a majority of mayors would hand control to Republicans (who control more but smaller towns), and so on. Opening the appointments process to popular vote would simply make an implicitly partisan competition explicitly so, as both parties would naturally endorse “their” favored commissioners and mobilize “their” voters in support and opposition. Independent redistricting commissions will always end up partisan.

If they can’t quite gain control of the commission, partisan agents on the commission can simply sabotage it, so that the commission is unable to produce maps and control reverts to an elected (partisan) legislature or an unelected (but still partisan) state supreme court. This sounds conspiratorial, but appears to have happened this year in both New York and Virginia. (Of course, in all cases, partisans blame the other party for the sabotage.)

Independent redistricting commissions don’t work. They help somewhat, but not enough—not as much as their supporters promised, and only until one party or the other finds a way to wrest control of it. Worse: once a party has control of the commission, the commission (which, remember, has been deliberately protected from political accountability in order to preserve its “independence”) cannot be fixed simply by voting really hard at the next election. You’re stuck with a subverted redistricting commission and an extended campaign to take it back… at which point now your party controls a subverted commission.

This is not a solvable problem. As long as redistricting allows discretion, it is a fundamentally political process. It can only be managed through the ugly hurly-burly of politics.

The key to reducing partisanship in gerrymandering, then, is not to change who gets to draw the lines. Any real-world line-drawing body, no matter how constituted, will be subverted by partisans.7 The key is eliminating the line-drawers’ discretion.

Promising Reforms Prohibited

At the same time, some of the restrictions Congress has imposed on the redistricting process—while perfectly constitutional and enacted for good reasons—have inadvertently cut off promising electoral reforms, which may have advantages over our current system.

For example, a large state like Pennsylvania might wish to elect its Congresspeople using the method currently used by the Scottish Parliament. In this system, each voter casts two votes: one for a specific candidate standing for election in her congressional district, and one for a political party. However, some Congressional seats are not assigned to any district, and are held “in reserve.”

After the votes are totaled up and the winner in each district is known, the statewide party vote is tabulated. Parties receive additional seats as a “top-up” if they performed well in the statewide vote but didn’t win a proportionate number of districts. These additional seats are assigned using an algorithm called the D’Hondt Method, which was invented by Thomas Jefferson and is currently used in many places around the world but (ironically) is illegal to use in Jefferson’s own United States!

That’s all very abstract, so let me give you an example. Imagine a state with ten districts. All of the districts are 55% Democrat and 45% Republican. Election Day comes and, sure enough, the Democrats win 9 out of 10 districts. (They lost the last one because of a weak candidate, which always happens somewhere.) Only 55% of the state’s voters supported Democrats, but they won 90% of the representation! Meanwhile, the state is almost half Republican, but only got 10% of the representation! Hardly seems fair.

Enter the “top-up” system. This state actually has 20 total Congressional seats, not 10! The first 10 were awarded by district election, but the other 10 were held in reserve. Because Republicans won far fewer districts than their vote totals suggest they “deserve”, the D’Hondt method awards them 8 of the top-up seats. Democrats get 2 of the top-up seats.

Final result: Democrats 11 seats, Republicans 9 seats. Democrats won 55% of the statewide popular vote and get 55% of the seats. Republicans won 45% of the statewide popular vote and get 45% of the seats. Meanwhile, each voter in the state continues to enjoy the benefits of local representation and local campaigns, since each still has a Representative in Congress who comes from the voter’s own district and is responsive to the special concerns of that district.

This system also encourages third parties, which are unable to win single-member districts outright, but which can often scrape together enough votes at the statewide vote stage to win a seat or two.

The system I have just described is called the “Additional Member System.” It is considered a mixed electoral system, because it includes both plurality representation (the winner-take-all districts in the “first round”) and proportional representation (the proportional adjustments in the “second round”). It’s not perfect (it tends to place more power in the hands of party bosses, for example), but it’s been mathematically proven that no voting system is.

There are lots and lots and lots of other electoral systems out there.8 Various election reformers would like to try bringing some of them to the United States. In our beautiful federalist experiment, some states may prefer one system, other states may prefer another, and most states likely want to stick with the current system, because they know it works. The states, as “laboratories of democracy”, should be able to try some of these ideas out and see if they work.9

But they can’t, because Congress—in its understandable zeal to stop parties from rigging the outcomes with at-large voting—banned all electoral systems for Congress except winner-take-all single-member districts.

The Redistricting Amendment

That leads us back to the text of our proposed amendment:

AMENDMENT XXX10

Section 1. If a state elects Representatives by electoral districts (whether its entire delegation or only a portion), all persons in the state shall be included in exactly one such district; each district shall elect an equal number of Representatives; each district shall be contiguous; the smallest district shall have at least nine-hundred-ninety-nine persons for every thousand persons in the largest district; and the average straight-line distance between each person’s residence and the geographic center of that person’s district shall be the minimum known to be possible at the time prescribed by state or federal law for the determination of districts.

Section 2. If a state elects multiple Representatives from any single district, it must use proportional representation to elect Representatives in all districts. Congress may enforce this section by appropriate legislation.

Section 3. Congress may not otherwise interfere with any state’s apportionment of districts for election to the House of Representatives, or its choice of plurality, majority, proportional, or mixed voting systems in elections to either house of Congress.

Section 3: Electoral Experiments Authorized

Section 3 permanently allows states to experiment with alternative electoral systems, and formally clarifies that Congress does not have authority to interfere in them.11 Since Section 3 forbids future Congressional interference even if one of the parties finds a way to exploit this amendment, the success of Section 3 depends on Sections 1 & 2 being exploitation-proof.

Section 2: No Multi-Member Shenanigans

Section 2 prevents states from doing shenanigans with proportional representation or multi-member districts. For example, a malicious state legislature could make some districts hold proportional elections but make other districts winner-take-all. It could also have at-large statewide elections without making them proportional, making the whole state winner-take-all. These systems could substantially dilute the opposition vote. It would be worse than what we have today.

Congress’s current blanket rule against single-member districts accomplishes the same goal as Section 2, but the current rule also prevents all those experimental electoral systems we talked about. Section 2 offers a still-robust but much narrower rule. Congress is authorized to enforce this section of the amendment (and only this section), presumably by giving precise definition to the phrase “proportional representation” so states can’t cheat around it with a pseudo-proportional system. But this section also depends on the rules in Section 1 creating fair district maps.

So the heart of this proposal is Section 1.

Section 1: Gerrymandering Outlawed

Section 1 mostly—mostly—takes the current rules for drawing district lines and enshrines them in the Constitution. If a state chooses to continue using electoral districts (and, under Section 2, it doesn’t have to; it could hold a single statewide proportional election instead), then it has to ensure that the districts are:

- Contiguous: all parts of the district connect

- Comprehensive: everyone in one and only one district

- Equal population: this proposal finally ends the current system where courts decide whether “close enough” is close enough. The amendment formally defines “close enough” as a 0.1% population deviation (“nine-hundred-ninety-nine persons for every thousand persons”). This is fairly stringent by current legal standards (which have allowed approximately ten times more deviation for court-ordained “good reasons”), but is perfectly attainable.12

- Compact: as I said before, compactness is hard to define, even harder to require, and impossible to fully reconcile with other goals like representing “communities of interest.” Compactness is also the keystone of any effort to stop gerrymandering. After all, what’s the problem with these maps?I can’t find the original source of this graphic (by Peter Bell), but the maps are from the 2011-2013 redistricting cycle. Some of these were eventually blocked by court order, but it took a while.

The problem is clear: these districts aren’t compact. They’ve been drawn with all sorts of wiggles and appendages in order to contain just the right voters (or just the wrong voters). This is exactly like the gerrymander in Elkanah Tisdale’s original cartoon from 1812. The heart of gerrymandering is trading district compactness for selfish electoral outcomes.

Our solution to gerrymandering, whatever it is, must put a knife through this tradeoff, once and for all. It must, above all else, mandate compactness. And that’s not all: our solution to compactness must be clear (so that it can be transparently obeyed), simple (so the voters voting on this amendment understand what they’re voting for and no loopholes can sneak in), short (you simply can’t write a five-page algorithm into a federal constitutional amendment), and exhaustive (so that the parties have no “discretion” that they can use to wheedle out partisan advantage).

There are a few well-known systems that could accomplish these goals, in various balances. For example, I think a convex-hull minimization algorithm would be really neat and probably draws great districts, but I also think it’s really hard to explain or understand what a “convex-hull minimization algorithm” actually is. I picked the method that I think strikes the best balance between these objectives, and (more to the point) the one that I think has the best chance of winning popular support in a national ratification campaign:

…the average straight-line distance between each person’s residence and the geographic center of that person’s district shall be the minimum…

This involves no fancy math and (unlike most compactness measures!) no mention of pi. Everyone knows how to find the center of an area on a map. Everyone knows how to measure the distance between his or her house and that center. Everyone knows how to do that for a bunch of houses and take the average. You can explain the entire rule it in a sentence. It’s just one little sentence in the amendment—not even a full sentence but a sentence fragment!—but I worked on writing that sentence for months, trying out various methods and finding them too complex for words. Minimum average distance works, and that’s why it’s in this amendment.

So let’s say it’s redistricting time, and we’re using this rule. The Republicans draw a map and the Democrats draw a map. Citizens can also draw and submit their own maps. So can computers. All maps meet the other requirements (contiguous, comprehensive, et cetera). You might see it as an open competition to draw the best map. The map that wins and becomes law is the one where people (on average) live closest to the center of their districts.

Why? Gerrymandered districts are ordinarily long, thin, and irregular, which means that most people in a gerrymandered district don’t live anywhere close to the district’s center. The lowest-average-distance rule makes it impossible to draw such districts and still win the competition.

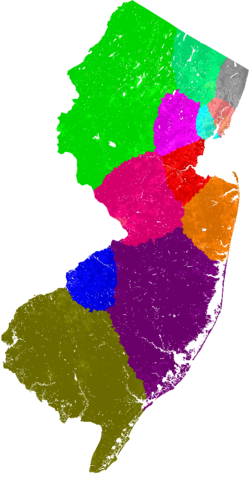

I know, a picture is worth a thousand explanations. Remember that ridiculous New Jersey map passed by an “independent” commission?

Here’s how a computer following the lowest-average-distance rule drew it, using the same census data:

Isn’t that just… an obviously better and fairer map?

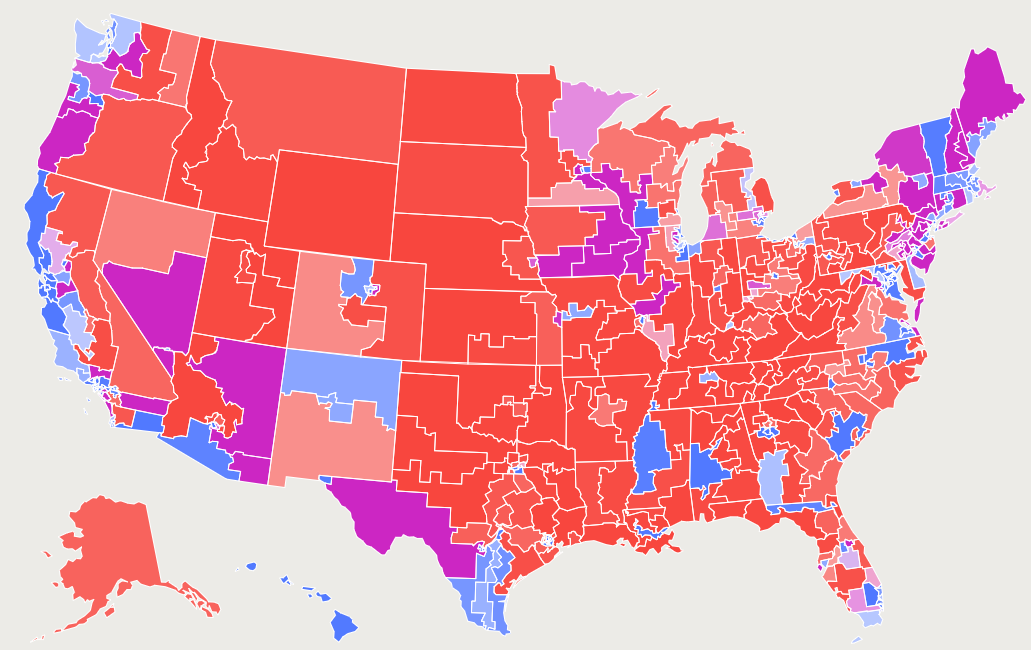

The national political effects of this would be delightfully neutral, too. In 2018, FiveThirtyEight published The Atlas of Redistricting, which showed what the map would look like if this technique were rolled out nationally. First, for comparison, here’s the actual map that existed in 2018:

Yikes. And here’s the map if it had followed the “least-average-distance” rule instead:

It’s just… better! Look how many fewer jagged lines there are in, I don’t know, Ohio.

Since neither party currently holds a clear long-term advantage from gerrymandering, the impact on national politics is modest and symmetrical. Under the actual 2018 maps, there were 195 Red districts, 168 Blue districts, and 72 highly competitive “purple” districts. Under the rule I’m proposing, there would have been 180 Red districts, 151 Blue districts, and 104 purple districts.13 So Red loses 15 safe seats, Blue loses 17 safe seats, and the nation gains 32 more competitive districts where the fate of the House of Representatives can be decided.

To me, that sounds like a pretty good deal for all sides! Gerrymandering ends forever, and neither side’s Congressional delegation gets hurt!

There is one caveat:

…shall be the minimum known to be possible at the time prescribed by state or federal law for the determination of districts.

The key improvement this system imposes on our system is that it eliminates discretion by imposing clear criteria for what counts as the “best” map out of a set of proposals. The key drawback, however, is that there is not (currently) a way to mathematically prove that a given map is the absolute best map possible. All you can do is try out different maps and check which one scores better.

The most popular algorithm for finding lowest-average-distance maps runs on a home computer, but takes “3-4 hours to find one solution to the California congressional map.” The author says he runs the solver for a couple of weeks in order to find the actual best fits. A state government, or an ambitious political party, or a university political science department, would have far more resources and could identify great maps much more quickly. A political party might very well discover a map with a very low average distances, but which takes away some of the party’s political advantages. The party might very well delete that map and pretend it never saw it. This would be unconstitutional, perhaps even a crime under state law, but, hey, political parties do crimes on the reg, so this is no surprise. Fortunately, since both political parties will be searching hard for maps, the other party (or some independent group) is likely to discover the same map, and publicize it. No harm done.

This amendment accepts that you can’t just keep letting people discover new and more refined maps right up until Election Day, because that would cause chaos, with maps in flux even while people are already voting. Instead, it allows the state or the federal government to set a deadline for discovering and submitting maps. (If both set a deadline, the Supremacy Clause means the federal deadline controls.)

Out of all the maps published by the deadline, the winning map is the one with the lowest average distance. No one gets any discretion. There is no room for map-rigging. Any attempt at map-rigging can be easily and fairly identified by any court, then blocked. The amendment’s text here is very broad (“known to be possible”), in order to prevent malicious state government from imposing onerous submission requirements and thereby ignoring good maps that the government happens to dislike. If the best map is public knowledge, then it must be used, even if its author didn’t fill out Submission Form KLM-47 in triplicate for the state’s paper-pushing department.

Section 1 would instantly and permanently end gerrymandering, by both parties, at the federal level, forever… while Sections 2 and 3 would simultaneously enable a new era of experimentation in alternative (and perhaps superior?) electoral systems, for states that choose to exercise their rights under federalism to try out alternatives. That’s a pretty big win, if I do say so myself.

The Sacrifices

This amendment still makes two sacrifices. One of them is something the Left will hate. The other is something the Right will hate. (And, reader, I really do hate it.)

The Left loses explicit race-based representation. Guaranteeing compactness leaves no room for any gerrymandering. Not the “bad” kind, of course, but also not the “good” kind, where well-meaning civil rights supporters gerrymander districts to get Black or Hispanic voters in control of a district of “their own,” a so-called “majority-minority district.” Under this amendment, there will still be majority-minority districts, because there are a lot of places in this country where minorities naturally form a majority! But there will no longer be a legal rule allowing legislatures or courts to force majority-minority districts into being just because it’s possible to do so. According to FiveThirtyEight, the current system produced 95 majority-minority districts in 2018. Under this amendment, there would have been only 89 majority-minority districts. Half a dozen districts is not a huge loss, and I think it is more than justified by the system’s overall gains in democracy (the amendment also prevents gerrymandering against minorities, which is huge)… but it is still the fewest majority-minority districts produced under any of the eight methods FiveThirtyEight evaluated.

For its part, the Right loses communities of interest—y’know, neighborhood districts. The Right loves that stuff, because it is human in a way that resists technocratic steamrolling. The system proposed in this amendment, by contrast, cares about only one thing: building compact districts by minimizing the average distance between the voter and the center of her district. It does not care about, or even know about, neighborhoods, ethno-national enclaves, city borders, or county lines. This system splits them up without the slightest heed, and it does so an awful lot. According to FiveThirtyEight, the current system splits county borders into multiple districts 621 times, and most other systems post similar numbers. But this system? 1,660 county splits. That’s a lot. Where I live, people drawing district boundaries typically try to respect the twists and turns of the Mississippi River, a major geographic, political, and demographic boundary here. The lowest-average-distance system doesn’t care at all, and it shows.

So be it. As we’ve seen, no system is perfect. If you want to kill gerrymandering—and not just kill it dead, but cut out its heart so it can never come back again—you cannot give legislators a bunch of discretion to draw racial gerrymanders or pick which specific “communities of interest” they want to avoid splitting up (a decision that can be used to manipulate the map in a thousand different ways). You can’t tie districting to county lines or city borders, because the state legislature can redraw those borders at will if it sees any political advantage in doing so. Explicit racial representation and district-based community representation are both lovely ideals… but they are not compatible with the goal of outlawing gerrymanders.

I think that’s worth it. I suspect, when the question is fairly put to them, the American People would, too. Pass the Anti-Gerrymandering Amendment before the 2030 census.

De Civitate is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Subscribed

Tag: #SomeConstitutionalAmendments

Except, arguably, in short stretches of 3 to 5 years, like the period between the disintegration of the Federalist Party (1815) and the financial Panic of 1819 / the Missouri Crisis (1820).

Although districts would not be legally required to be of equal size until the late 19th century, and this would not be declared a constitutional requirement until Wesberry v. Sanders in 1964, the Founding generation was well aware of the importance of equal-sized districts. “Rotten boroughs” in Parliament were already a substantial political concern in England by the end of the 18th century. Unfortunately, the demands of the Chartists and their precursors would not catch fire until after the Constitution was ratified, and their wise reforms did not make it into the federal Constitution, although many states would adopt some form of equal-population rule.

The gerrymander is named after Elbridge Gerry, whom you may recall as the hero of my most recent article on constitutional amendments. Unfortunately, for all his democratic bona fides, Gerry is the one who signed the redistricting plan that created this most famous of all gerrymanders, and it is what he is principally remembered for today. Never do bad things, because people will always remember the worst thing about you the longest.

You can refute the entire legal theory of Reynolds v. Sims, the foundational text of our modern districting case law and its “one person, one vote” theory, in just six words: “The United States Senate is constitutional.”

See Robert B. McKay’s paper, “Federal Analogy and State Apportionment Standards,” for the official response (formally blessed by the Court in Sims). However, my principal reaction to this paper is to gawp at the sweeping, because-I-said-so declarations about extra-constitutional “equalitarian principles” which evidently passed for sophisticated legal reasoning in the early 1960s.

Floterial districts (where a single citizen may live in two or more overlapping electoral districts) have some useful applications and are currently used in (I believe) three states, but they are currently illegal at the Congressional level under the comprehensiveness rules. The main purpose of floterial districts is preserving communities of interest while relieving population disparities between those communities.

Technically, multi-member districts and at-large congressional elections were outlawed from 1842-1850, 1862-1932, and 1967-present.

Well, technically technically, they were legal from 1929-1932, but nobody was sure until Wood v. Broom. There were also significant constitutional doubts in the 1840s about whether Congress had the authority to outlaw multi-member and at-large districts, and several states ignored the original statute. Those doubts were never really settled, to my knowledge, but the states in question eventually switched to single-member districts anyway. The amendment proposed by this article would finally resolve those constitutional doubts in favor of the states.

For more information on the history of multi-member and at-large districts for House of Representatives see FairVote’s history.

In addition, several state legislatures continue to use multi-member district elections, including South Dakota and Washington. Also, the odds are good that your city council runs on some kind of multi-member system, with (usually two) representatives elected from each ward or precinct.

A Canadian friend of mine observes that Canada doesn’t have this problem. Nor does much of Europe. This is not because their election system is somehow more insulated from partisanship than ours is; it is because their national mood is much less riven by partisan discord than ours is, so their system doesn’t need partisan insulation. Any Canadian districting system will be less polarized than any American districting system, because Canadians are less polarized in general.

The reasons for the lower level of polarization in (some) other parts of the world is beyond the scope of this post, but suffice to say for now that our polarization does not appear to arise from some fundamental defect in the American political system or the American moral character, although having our executive branch be separately elected may exacerbate it. Rising populist movements the world over, including Canada’s trucker protests last year (and the dictatorial powers invoked to suppress them) suggest the veneer of non-partisan Euro-Canada stability may be more fragile than it appears.

We’re not really talking about vote-counting methods today, but, if you’re interested in voting methods, Woodall’s Condorcet method (also here) (also here) is better than Instant Runoff is better than first-past-the-post. Instant Runoff mostly gets you closer to the “correct” Condorcet winner of an election and is generally better than our current system, but it has some very bizarre random effects where it occasionally elects a fringe radical for no reason. IRV supporters are, like, “The 2009 Burlington mayoral election was just one time; stop beating that dead horse!” but, no, the 2009 Burlington mayor mess is an inherent feature of IRV. In that case, it randomly elected a fringe left-wing candidate (which my left-wing friends are inclined to see as a feature), but there’s no inherent reason it couldn’t just as easily elect a fringe right-wing candidate.

Supporters of alternative election systems may ask: this is a constitutional amendment, which can do anything, so why are we simply opening the door to modest experimentation, rather than turning over the apple cart and, say, reinventing the House of Representatives as a national parliament with national “top-up” seats while disempowering the Senate? Fair question.

Remember the premise of this series: we are trying to develop structural, non-polarized constitutional amendments that could, theoretically, actually achieve 85%+ popular support and get ratified. A proposal to transform Congress into a parliament could never possibly pass, firstly because the American People prefer incremental to radical change, secondly because the small states vigilantly guard their Senate power (as they have since the Founding), thirdly because a “national parliament” would (under present circumstances) greatly empower the Blue tribe over the Red and therefore cannot win Red support, and fourthly because it’s actually a bad idea, because the Senate is good and the House of Lords is bad. (We’ll talk about why we need the Senate when I eventually get around to proposing Some Constitutional Amendments for the Senate, but I touched on it in my proposal for a new Origination Clause.)

Starring Vin Diesel as Xander Cage!

This would be a reversal of the current understanding. See footnote 6, above.

The method prescribed by the amendment is also not quite the same as the method currently used by the courts, which requires several paragraphs of explanation. Basically, under today’s rule, you look at every district and calculate the percentage difference between its population and the “ideal” population. The largest answer you get is the map’s population deviation. The method I am proposing makes a direct comparison between the largest and smallest district. This is more stringent, but is not precisely comparable.

I played around with Districtr for a while to see how they differ. On an idealized map, a 0.5% population deviation under the current system counted as a 1.0% population deviation under the proposed amendment. On a more realistic map, a 7.3% deviation under the current system would count as an 11.7% deviation under the proposed amendment.

In any event, the method proposed by this amendment will always yield districts that are much more equal than current court precedent allows, and, as BDistricting has convincingly shown, these very equal districts are readily attainable everywhere in the union, at every level

For the record, even though I am siding with the lower court in Tennant v. Jefferson County Commission and against the Supreme Court in terms of the policy outcome, I do think that, under current law, the Supreme Court’s decision was legally correct. Current law allows some balancing. This amendment, for reasons discussed in the article, does not.

Despite having a similar number of voters, Reds still have more “safe” seats than Blues under both methods. This is not because of gerrymandering, but because of geographic maldistribution, which is a fancy way of saying that too many Blue voters live in dense, intensely Blue areas. Their votes end up “wasted.” This is a decent argument for Blue voters to pursue proportional representation and/or ranked-choice voting, and a warning to them that their epistemic bubble is likely substantially stronger than Red voters’. It is also a whole separate topic that we are not delving into today.