I’ve concluded the De Civitate Poor-Man’s Stop-Trump delegate tracker with a final entry marking the climactic defeat of May 3rd.

“We May Yet Prevail”

Since last week, when I wrote that it all comes down to Indiana, the situation has become desperate. According to reliable reports, internal polls, which seemed merely shaky when I wrote my piece, have since gone into free-fall. Public polls of Indiana, which finally became frequent enough to become reliable after April 26th, have gone from bad to catastrophic. FiveThirtyEight now rates Trump as having a 90% chance to win. I have long maintained that we must fight on against Trump, even if Indiana is lost. I have said that we have a small chance even with a narrow loss in Indiana. Well, I still say we must fight on. But, if Trump wins by the vast margins suggested by the polls, it won’t be narrow, and we won’t have a chance.

The conservative movement, which has made its home in the Republican Party for decades, faces the abyss. Trumpism, a philosophy based on thuggery, resentment, and complete epistemic closure, is poised to take its place in a new coalition with the East Coast Establishment… leaving conservatism in the wilderness.

One imagines Ted Cruz touring his Indiana headquarters tonight, preparing for what may be the final battle against Donald Trump, and reflecting on the future, as Captain Picard once did before the Enterprise‘s great battle against the Borg:

It All Comes Down To Indiana

“If Trump wins every single delegate of the night, that’s unfortunate but not entirely unexpected. Tonight’s tactical voting is to minimize the damage, not to actually make any gains. Indiana is the race that matters, and they’re on May 3rd.”

–Me, April 26th

“The time to panic is on May 2nd, if Kasich is still in the race the night before the pivotal Indiana primary and splitting the anti-Trump vote. That could easily hand Trump the nomination.”

–Me, April 19th

“Thus, I expect Trump to win virtually all the delegates in those primaries; so do most analysts. This wouldn’t be all that bad, either, as long as it drives Kasich definitively out of the race before the pivotal (and very competitive) Indiana contest on May 3rd.”

–Me, April 6th

“As long as Trump is denied delegates in Wisconsin, Indiana, and most of California, and Cruz takes the states he’s already expected to take (South Dakota, Nebraska, Montana, etc.), Trump will not have 1237 bound delegates going into the convention… even with the whole Northeast under his belt.”

–Me, March 25th

“By this point, if Rubio and Cruz are both still in the race, still splitting their vote against a 40% popular Trump, it’s probably too late to stop Trump.”

–Me, February 27th, speaking about a field that remains divided against Trump through Indiana. I had the identity of the spoiler wrong — it ended up being Kasich — but not the importance of Indiana.

There are ten contests left in the 2016 GOP primary season, but two states matter more than all the rest: Indiana, which votes May 3rd, and California, which votes June 7th.

Tactical Voting Recommendations, 4/26

I don’t love tactical voting — it is both vaguely distasteful voting for someone you don’t much like for the sake of someone you do, and really hard to coordinate — but I also want my candidate to win this primary, and that can (for most practical purposes) only happen if the frontrunner is prevented from reaching 1,237 delegates on the first ballot. The 2016 primary is on a knife’s edge; Mr. Donald Trump is better-than-even odds to clinch the nomination… which means denying him every possible delegate is critical for any other outcome. Tactical voting is called for.

So, if you support Ted Cruz, John Kasich, a convention dark horse like Paul Ryan, or simply oppose Donald Trump, here are the votes I think you should cast tonight in order to maximize your chances of winning (and mine).

PENNSYLVANIA: Cruz. Cruz and Kasich are close in the polls, but Cruz has the edge and a superior ground game, which will help him convert polling support to actual support more efficiently. Still, Trump is far enough ahead that this is likely to be a bloodbath. Only question is how well the Trump slate does among the unbound delegates. (PA has an unusual hybrid primary; don’t ask.) I expect Trump to win the statewide vote (17 bound delegates) and about 45 of the 54 unbound delegates, plus or minus 8.

RHODE ISLAND: Cruz. The state’s proportional, so it *shouldn’t* matter which non-Trump you vote for (there’s no spoiler effect in a true proportional race), but Cruz needs to stay above the 10% viability threshold (he’s currently on the bubble at 13%), or the delegates he would have won go to Trump instead. Trump should get 8-12 delegates here.

CONNECTICUT: Kasich. Trump will likely win all the delegates in the state, but there is still a remote chance that Kasich could win one or two congressional districts if the anti-Trump vote consolidates behind him, which would net him 3 delegates, and hold Trump below a 50% winner-take-all threshold for statewide delegates. There’s a 20% viability threshold which Cruz has a very low chance of making, and which won’t be useful if Trump hits 50% anyway, so Kasich is really the right call here. I still think Trump wins all 28 delegates, but on a very good night, he might be held to 19.

DELAWARE: Cruz. Trump wins all the delegates either way. There is no clear anti-Trump right answer and Trump leads both by 40 points anyway. Cruz then becomes the default anti-Trump answer, on the basis that, if Kasich is sufficiently humiliated on 4/26, he might drop out, making the anti-Trump campaign much easier. If Trump doesn’t win all 16 delegates here, it’s a yuge upset.

MARYLAND: Kasich. According to PPP, Kasich polls ahead of Cruz in every district of Maryland. This surprises me, as Maryland District 6 seemed like prime Cruz territory to me, but we have to trust the data over our instincts. Vote Kasich in Maryland. Trump should still win something like 32 or 35 of Maryland’s 38 delegates, but every non-Trump win counts.

OVERALL: Look, 4/26 is going to be bad for anti-Trump forces, but we’ve always known that, literally since early February. If Trump wins every single delegate of the night, that’s unfortunate but not entirely unexpected. Tonight’s tactical voting is to minimize the damage, not to actually make any gains. Indiana is the race that matters, and they’re on May 3rd.

The most interesting development of the week, of course, is the Cruz-Kasich alliance. I’m going out of town for a couple of days, but I’ll comment about it when I get back (for you, gerv!). By then, we should have a little more data about how it’s playing with the public.

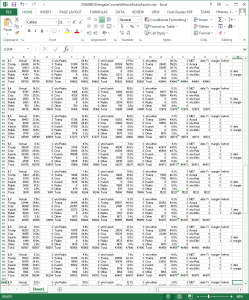

De Civitate’s Delegate Loyalty Tracker

UPDATE 10 MAY 2016: In light of Trump’s presumptive nomination, Saturday’s delegate results (which were basically “Everything’s Coming Up Trump”), and the fact that it has become even harder to track delegate loyalties now that there’s only one candidate in the race, nobody’s asking the question, and once-loyal non-Trumps are now falling in line behind Trump… in light of all this, I have decided to stop updating this post, and this spreadsheet. As far as I know, @TodayInTheZach is going to ride it out to the convention, but I was chiefly interested in second-ballot loyalties and rules-change support, and it is now clear that Trump will have what he needs on both fronts. Thanks for reading!

Original post 14 April 2016 – Last updated 1 May 2016 – Spreadsheet here

You’ve seen in a lot of places, including De Civitate, that the Republican race right now looks something like this: Trump 761 delegates, Cruz 540 delegates, Kasich 144 delegates. Different sources have slightly different numbers, but the basic message is the same.

What if I told you that, as of today, Cruz actually has 276 delegates, Trump 181 delegates, and Kasich 105? (UPDATE: These figures are from April 14th; current figures below.)

Well, that’s exactly what I’m about to tell you.

We at De Civitate have argued recently that it is not delegate bindings, but delegate loyalties, which will decide the outcome of the GOP 2016 convention. Supporters-in-name-only (or “SINOs”), who are bound to vote for one candidate on the first ballot but hope to carry a different candidate to victory on a later ballot, could dramatically change the terrain of the convention. For example, a bunch of delegates bound to Trump but loyal to Cruz could throw their support to Cruz on the second ballot, swinging the nomination to Cruz. Or a bunch of delegates bound to Kasich but loyal to Trump could, with a clear conscience, cast their votes for Kasich but consistently vote to sustain existing convention rules (namely Rule #40(b)) which would prevent those votes from actually being counted for Kasich.

Our position seems to have been borne out by events. Since we started writing about this, we’ve seen story after story about the Cruz campaign out-organizing both campaigns (making much better deals, you might say) in the delegate-loyalty battle. Cruz is securing the loyalty of his own bound delegates while getting loyal Cruz supporters into bound delegate slots for Trump and Kasich… which places Trump in a very tough position on a second ballot and may well make a Kasich nomination totally impossible.

We have also argued that it is nearly impossible to track delegate loyalties, because delegates do not step up to a big ledger at the end of an election to mark down their loyalties.

That turned out to be true, too. Tracking down the loyalty of each individual delegate to Cleveland is really hard work. In the end, though, that didn’t stop us. Here are our results:

Original post 14 April 2016 – Last updated 1 May 2016 – Spreadsheet updated continuously

| Candidate | Loyal Delegates | |

|---|---|---|

| Cruz | 458 | |

| Trump | 399 | |

| Kasich | 141 | |

| Anti-Trump | 143 | |

| Uncommitted | 58 | |

| Unknown | 196 | |

| Remaining | 1077 (50%) | |

The state-by-state data, along with links to all the online sources used to put it together, are in this Google spreadsheet. Most delegates are chosen in April and May, so we expect to see a lot of fresh developments in coming days. We welcome corrections, comments, arguments, and improvements; putting this together and double-checking it solo has not been easy!

As far as we know, De Civitate is the only place on the web tracking this information systematically. Judging by how this election season has gone so far, we expect FiveThirtyEight to have this idea independently and launch a much cleaner and more graphically attractive version of this tracker in about two weeks. Until then, though, you’re stuck with De Civ!

(UPDATE 4/21: Maybe you’re not quite stuck with us after all! We owe a very large debt of thanks to @TodayInTheZach, whose incredible spreadsheet, which we discovered this week, filled in a great many holes in ours, as well as showing us a much saner way of organizing the data. We were also able to fill in a few gaps in his — with hopefully more to come!)

(UPDATE 4/30: I was out of town during the Tuesday Trump Romp, so wasn’t able to stay up-to-date. Another thanks to @TodayInTheZach, who did the legwork, which I promptly expropriated to my spreadsheet.)

Conventional Chaos, Part 3: The Republican Rulebook

I have a lot of friends who are asking a lot of questions about brokered conventions these days. In this series, Conventional Chaos, I’ll be explaining how a Republican party convention works… and why 2016’s convention could be very different from the dull pageants we’ve seen since the 1970s. In Part 3, we’ll take a close look at the rules and procedure governing the convention. If you’re just joining us, start with a basic overview of the convention process in Part 1 and the deep dive on delegates in Part 2.

There is a book called the Rules of the Republican Party. It’s a short book, barely 15,000 words long, yet it dictates the entire process by which Republicans pick their president. The book divides neatly into three parts.

The first part (Rules #1-12) serves as the Constitution of the Republican National Committee. The RNC is a group of Republican leaders who work year-round to elect Republicans to office.

The second part of the rulebook (Rules #13-25) describes, in broad terms, how the Republican primary system works. As you remember from previous posts, the purpose of the Republican primary process is not to pick a presidential nominee. The purpose of the primary process is to select several thousand elected officers of the Republican Party, called delegates, whose job is to represent their state party at a giant meeting of all fifty state parties. This meeting is called a national convention, and it is held exactly once every four years — always in a presidential election year. The delegates, chosen by the voters to represent them, then choose the Republican nominee for president. Rules #13-25 determine how many delegates each state gets to send to the convention, establishes the overall schedule for the primary system, and mandates punishments for states that break the rules. It’s basically the Constitution of the Republican primary process.

The third part of the Republican rulebook (Rules #26-42) is the shortest and least detailed. It governs procedure for the national convention itself. It describes how voting happens, how state delegations can propose changes, who can speak and when and for how long, and, ultimately, what it takes to become the Republican nominee for President of the United States. This part of the rulebook serves as a kind of Constitution for the national convention.

Every four years, just after the start of the national convention, the rulebook expires. The convention delegates must then revise it (or renew it without changes). Until the delegates have officially approved rules for the next four years, the convention is unable to take up any other business, like the party platform or the presidential nomination. This makes sense: the party would be unable to operate after the convention — or even finish the current convention — without rules to govern it throughout.

Not only is a national convention required to revise the rules, but, traditionally, only a national convention can revise the rules. The RNC can’t normally* mess around with the rules between conventions: the delegates have one shot, every four years, to get it right.

Because the party depends on good, solid rules at every level in order to function, and because it has to get those rules right the first time, the process involves a great deal of intricate deliberation over the course of several months. Even in an “easy” convention year, with nobody but nerds like me paying attention, rules negotiations are as tense as they are arcane. This year… God only knows. Let’s walk through the rules-revision process together.

Flip open your Rulebook to page 9. (Note that we are using the most recent revised version of the rulebook, from August 2014, which is not the version actually passed by the 2012 national convention; there are several minor differences. Additionally, I thought the 2014 rulebook on the GOP website was ugly, so I reformatted it to look like the 2012 rulebook.) Under Rule #10(a)(1) — and don’t freak about about that nerdy-looking parenthetical notation, it just makes it easier to find the right paragraph! — you’ll find this instruction:

There shall be a Standing Committee on Rules of the Republican National Committee, composed of one (1) member of the Republican National Committee from each state, to review and propose recommendations with respect to The Rules of the Republican Party.

Simple enough. There’s a bit more detail, but we don’t need it. The Standing Committee on Rules is the first piece of the puzzle. There are 56 members of the Standing Committee on Rules, one for every state (plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the four territories). They are elected very indirectly; according to Rule #1(a), each state party gets three RNC members, who are usually chosen by some kind of state party election or state convention. Those three people then get to “elect” one of themselves to be the state’s representative on the Standing Committee. (There are other Standing Committees, like the Standing Committee on the Call, but, in this post, we only care about the Standing Committee on Rules.)

The Standing Committee’s job is normally very boring. It handles rules disputes between conventions. Between 2012 and 2014, it was also allowed (very unusually) to recommend changes to the rules, although it could not actually make any without supermajority support on the RNC. When primary season heats up, their job gets more exciting: under Rule #17(e), the Standing Committee has the authority to punish state parties for holding primaries that violate the rules. For example, in 2008 and 2012, when Florida held its winner-take-all primary very early (in violation of an earlier version of Rule #16(c)), the Standing Committee on Rules recognized the rules violation, voted on it, and applied the penalty: Florida lost half its delegates.

But the Standing Committee’s most important job comes late in the primary season, at the Spring Meeting of the RNC. This year, it’s happening on the week of April 17th — just a few days from now. At this final meeting of the Standing Committee before the convention begins, they issue a set of recommended changes to the current rules. That’s all: recommendations. Those recommendations are then passed to the next piece of our puzzle: the Convention Committee on Rules.

The “Convention Committee on Rules and Order of Business” is established by Rule #41(a):

There shall be four (4) convention committees; the convention committees on the Platform, Credentials, Rules and Order of Business, and Permanent Organization of the convention…. The Delegates elected or selected to the convention from each state… shall elect from the delegation a delegation chairman and their members of the convention committees on the Platform, Credentials, Rules and Order of Business, and Permanent Organization of the convention, consisting of one (1) man and one (1) woman for each committee.

So, unlike the members of the Standing Committee, the members of the Convention Committee aren’t elected or appointed by RNC members, and thus aren’t (necessarily) insiders. Every state (and territory) gets two Convention Committee members, for a total of 112 members, and the only restriction is that each state must elect both a man and a woman — an affirmative action rule that is weirdly common in the Republican Party, given the GOP’s official opposition to affirmative action — who must both be national delegates from that state, and who must be elected to the Convention Committee by the other national delegates from that state.

So who gets picked for the Convention Committee from each state depends a lot on how that state chooses delegates, a diverse process we discussed last time. In states like Hawaii, where the national delegates are picked by the winning candidates, the Convention Committee members will probably be consummate insiders, like all of Hawaii’s delegates. But in states like Alabama, where national delegates are elected directly on the ballot by primary voters possessed of a strong anti-establishment sentiment, the Convention Committee members are likely to be anything but insiders. Indeed, since I started writing this post, it looks like Alabama’s delegation announced its Convention Committee members: a little-known state legislator named Ed Henry and a kind-looking woman named Laura Payne, who appears to have no online presence beyond her mostly-private pro-Trump Facebook page (both are Trump supporters; please do not harass them). About as outsider as you can get!

The Convention Committee’s job is as simple as it is contentious: they need to review the recommendations made by the Standing Committee, then either approve them, reject them, or revise them. In effect, all the months the Standing Committee spends debating various rules changes boil down to a single document that is then used as a starting point by the Convention Committee, which is free to chuck all the work of the Standing Committee out the window and start fresh if it wants. The Convention Committee must be given a copy of the Standing Committee’s recommendations by June 18th, 2016 (as stated in Rule #41(d)). The Convention Committee then meets just a few days before the convention, and keeps at it until it produces the “Report of the Convention Committee on Rules and Order of Business” — an agreed-upon package of rules changes and renewals that is approved by majority vote of the Convention Committee.

In rare cases, the Convention Committee is deeply divided, and produces two reports instead of one: the “majority report,” supported by the majority of the committee, and a “minority report,” supported by at least 25% of the committee (Rule #34).

So does the Report of the Convention Committee on Rules and Order of Business become the new Republican rulebook? Nope! They’re just a recommendation, too! The Convention itself still has to weigh in!

The convention actually opens on July 18, 2016. At that time, the Standing Committee and the Convention Committee will both have made their recommendations, but the 2014 Rulebook will still be in place for the start of the convention. (Rule #42 says so.)

The start of the convention follows an Order of Business determined by the RNC itself. (Rule #26 says so.) Those of you who, like me, find that level of direct control by the GOP Establishment alarming will be pleased to know that Rule #27 goes on to say that the convention can’t do anything important until the real Rules and Order of Business, proposed by the Convention Committee, have been officially debated and either approved or revised. So these opening actions of the convention, orchestrated by the RNC, are going to be the least exciting parts of the convention: going by the 2012 Order of Business, we can expect to see the Pledge of Allegiance, the official reading of the 2016 Call to Convention, a memorial to all the Republican officials who died since 2012, and the election (by the convention, not the RNC) of temporary officers to handle said pledges and prayers and readings and speeches. It’s not the RNC doesn’t want to control the process more; it’s just that they mostly can’t.

Meanwhile, in the background, the Convention Committee on Credentials is going to be resolving any disputes about the validity of certain delegates. This is the real action during the start of the convention. Every once in a while, a state party just completely fractures, or even cheats, and two different delegations from a state show up at the national convention, each group claiming to be the “true” delegation from their state. This happened in Maine in 2012, and it’s happening today in the Virgin Islands. These disputes are resolved mainly prior to the convention by the Standing Committee on Contests (Rules #23-24), but the Convention Committee on Credentials is the final court of appeals (Rule #25(b)), and this is when it does its work (Rule #25(a)). Contests are a complex and messy business, which we will avoid in the interest of brevity (ha!)… and because it doesn’t look, at this point, like there are going to be any unusually exciting contests this year. Mr. Trump may throw a temper tantrum about how badly he got out-dealed in Colorado and Louisiana, but he has no case under the rules for an actual contest, so this will be irrelevant. The convention will not hinge on credentials the way it will hinge on the rules.

Finally, when all delegates have signed in and all contests are finally resolved, the boring parts are over! The Convention Committee on Credentials is able to announce an official list of who is an actual delegate to the 2016 convention (the “report of the Convention Committee on Credentials”). According to Rule #27, this must be the first non-boring thing to happen at the convention. The convention delegates who weren’t being contested (also known as the “temporary roll;” see Rule #22) now vote on the Credentials Committee report. If they approve that list, the list becomes the “permanent roll” of the convention, and delegates on the permanent roll are officially allowed to be on the convention floor and cast official votes. Yay! Four paragraphs since the convention opened and all we’ve done is establish who the delegates are!

But now that we know the delegates, the convention can get to the good stuff. Most likely right after the permanent roll is approved, the convention will elect permanent officers to manage the rest of the convention: a chairman (traditionally the highest-ranked Republican in the House of Representatives; in 2016, that would be Speaker Paul Ryan), a Secretary, a Parliamentarian, a Sergeant-at-Arms, and their respective deputies.

Once that’s done, the convention can finally get to the rules. The report of the Convention Committee on Rules is either read from the podium or distributed to the delegates (both reports, if there is a minority report). Then there’s an up-or-down vote on whether to approve the majority report as-is. As far as I know, the report has always (officially, at least) been approved without modification.

But if the convention delegates don’t like what the Convention Committee on Rules has recommended — which could easily happen, in this year’s closely divided convention — the vote could easily fail, and then we’re in for a classic rules floor fight. Another possibility is that some factions with substantial support will propose changes just before the majority report comes up for a vote — setting up a rules fight that would be only slightly less messy.

I’ve been in a couple of floor fights over rules (at the local/state level), and I’ve witnessed a couple others. Floor fights about rules are generally quite fair, because every faction can offer its own proposals (“let’s use the minority report,” “let’s keep the majority report, but tweak Rule #40(b),” “let’s throw the whole thing out and use this document my state delegates wrote instead,” etc. etc. etc.), everyone gets to debate the pros and cons of every motion, and, in the end, everyone gets their say by a free, fair vote. Eventually, a rules document is approved that has the support of a majority of the convention.

But it takes ages, because being fair to two thousand individual delegates takes time. My first rules fight was at a district convention that was supposed to run from 9 AM to Noon. There were perhaps two hundred people in the convention hall when the battle broke out. We finished the rules fight some time after 3PM, as I recall; the business of the convention, which remained contentious throughout, did not conclude until 11-something PM. It was thrilling, but exhausting, and very expensive for our hosts. (A bit like this post!)

Once the 2016 convention has adopted, by majority vote, new rules, that is the moment when you can finally throw out your 2014 rulebook. At that moment, the 2016 rulebook, whatever it says, comes into effect. The work of the Standing Committee and the Convention Committee on Rules may or may not be reflected in that new rulebook; it all depends on the 2,427 delegates, who can either accept the Committees’ recommendations or throw them out.

The bottom line is that the delegates themselves get the final vote (really, the only vote) on the rules that govern them — not the RNC, not any arcane Convention Committee, and not any presidential candidate. Those outside entities do get to advise the delegates and make recommendations, but the delegates decide, on the convention floor, by majority vote of 1,237, and no candidate bindings or other restrictions apply to any of them. The delegates are free to vote however they think best. This gives the delegates immense power, even if they are bound to a particular candidate, and is a major reason why delegate loyalties, and not delegate bindings, are what ultimately decide the result of a convention. The rules they adopt could simply be a few tweaks to the old rules. Or the new rulebook could be a page-one rewrite, with no resemblance to the old. We’ll all find out in Cleveland.

Only after the delegates have agreed to new rules are they able to begin working on the real meat of the convention: the creation of the party platform and the nomination of presidential and vice presidential candidates. Those processes will be governed by the new rules, whatever they turn out to be.

In the next part of this series, we’ll discuss why, despite all this — and despite the fervent wishes of the Wall Street Journal editorial page — the new rules will most likely be exactly the same as the old ones.

FOOTNOTES

*There is an exception to the “traditional” rule that only a convention can amend the rules: from 2012-2014, the RNC was permitted, under Rule #12 (passed at the 2012 national convention) to change the rules on its own, by a three-quarters supermajority vote. This highly unusual provision expired on September 30, 2014.

Delegate Tracker Update for April 6th

Just an FYI: I’ve updated the Poor Man’s Stop-Trump Delegate Tracker following the anti-Trump triumph in Wisconsin on Tuesday.

In Which I Am Right: Shadow Primary plus Kasich

In my recent piece on convention delegates, I speculated that, in the scrum to win the loyalty of as many delegates as possible, Ted Cruz would have the edge. Cruz has a strong organization, has been gearing up for precisely this fight for over a year, and his base is both a lot larger than Kasich’s base and a lot more active within the GOP than Trump’s. This might allow Cruz to secure the loyalty of delegates bound to him, as well as capture the loyalty of delegates bound to others.

Early indicators suggest this might be right.

A story from Politico yesterday discusses South Dakota’s delegation, which Cruz apparently dominates. But this is not too surprising, because South Dakota is prime Cruz Country: a Midwestern conservative plains state with an especially arcane delegate election method (delegates are chosen in convention before the primary on June 7th). I would be surprised if Cruz did not win the state outright, ending up with 29 bound delegates who are also totally loyal to him.

Conventional Chaos, Part 2: Delegated Disloyalty

I have a lot of friends who are asking a lot of questions about brokered conventions these days. In this series, Conventional Chaos, I’ll be explaining how a Republican party convention works… and why 2016’s convention could be very different from the dull pageants we’ve seen since the 1970s. In Part 2, we’ll take a close look at the delegates — and why the official delegate count tells you less than you think. If you’re just joining us, start with a basic overview of the convention process in Part 1.

So there will be 2,427 delegates at the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland. But who are they? What will they do? What can they do?

Bound or Unbound?

As we discussed in our last post, most Republican delegates are bound, which means they are required to vote for a specific candidate at the convention, regardless of their personal feelings, at least up to a certain point. Some Republican delegates are unbound,* which means they can vote for whichever candidate they prefer, at any time. There will be approximately 170 officially unbound delegates at the convention (from Wyoming, North Dakota, Colorado, and several U.S. territorial possessions like Guam), plus 60-90** bound delegates who became unbound when their candidates dropped out. (Only a few states allow this.)

This means the convention will have around 230 unbound delegates and 2,242 bound delegates. (1,237 delegates is enough to form a majority.)

Who Will The Bound Delegates Be Bound To?†

The binding of the delegates is the great question of the primaries, to which the Associated Press and the Election Wizards devote nearly all their energies, and the primaries aren’t over yet. As of today, 754 are bound to Donald Trump, 465 to Ted Cruz, 112 remain bound to Marco Rubio, 144 to John Kasich, 111 are unbound, and 10 remain bound to other minor candidates (Bush, Carson, Fiorina, and Paul).

By the time the convention rolls around, there are four likely scenarios. Bear these four scenarios in mind, because we’ll be coming back to them in future posts. The first three scenarios are (more or less) taken from FiveThirtyEight; the last is based on Kasich dropping out.

Quantifying the Kasich Spoiler Effect

According to exit polls, if John Kasich dropped out of the presidential race, 45% of his voters would stay home. 37% would vote for Ted Cruz. 18% would vote for Donald Trump.

These are the numbers FiveThirtyEight computed last week, which I then used after the March 8th primaries, and which were confirmed, broadly speaking, by exit polls after the March 15th primaries. Today, I am using them once again. After all, it is now mathematically impossible for Kasich to actually win the nomination during the primary season, and, thanks to Rule 40(b) of the Republican Party (which I’ll be discussing a lot more in the upcoming parts of Conventional Chaos), it is almost impossible to foresee him even winning enough states to have his name entered into nomination, and even less possible to foresee the convention changing Rule 40(b) to help out Kasich, given that the convention will almost certainly be controlled by a mix of Cruz and Trump supporters, both of whom want Kasich out. By any rational measurement, Speaker Paul Ryan has a better chance at the GOP nomination than John Kasich.

So the only effect of continuing the Kasich campaign — and Kasich surely knows this — is to take votes away from Ted Cruz, allowing Donald Trump to win an outright majority of delegates and win the presidential nomination. (In fact, because staying in reduces the chance of a brokered convention, Kasich has a better shot at the presidency if he drops out!) One wonders: is Kasich simply so overconfident about his appeal to the Northeast that he actually believes he can win, or is he deliberately helping Donald Trump in the hopes of winning the vice-presidential slot on a Trump ticket?

For now, that’s not a question we can answer. Here’s one we can, though: exactly how much Kasich is helping Trump? We’ll go through the March 15th states one by one and see how many delegates were lost to Trump because of Gov. Kasich. (We’ll do the same for Marco Rubio, simply for transparency, though Rubio has since done the honorable thing and dropped out.)

| MISSOURI | Actual Result | w/o Rubio | Cruz Alone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trump | 37 | 20 | 0 |

| Cruz | 15 | 32 | 52 |

| Kasich | 0 | 0 | – |

| Rubio | 0 | – | – |

| Trump Margin | +22 | -12 | -52 |

In Missouri, Kasich blocked Cruz not just from winning, but from climbing over the 50% threshold, which would have activated a winner-take-all clause that would have handed Cruz all 52 of Missouri’s delegates. Instead, Trump walked home with the majority of those delegates… despite winning by only 0.2%.